Exterior views of the Butler Street and West Mitchell Street CME churches. Warren LeMay, Wikimedia Commons and Terry Kearns, Flickr

“Long live the CME Church,” proclaimed Evelyn Hood.

Mrs. Hood, 96, is a retired Atlanta Public School principal and the former national president of the Sigma Gamma Rho sorority. She has been a member of the Christian Methodist Episcopal church since she was a little girl and she said she has watched how the church has evolved into a steadfast spiritual and religious force in Atlanta’s African American community.

Originally called the Colored Methodist Episcopal church, the church’s history is rooted in America’s original sins: slavery and racial segregation. It was out of this experience that the church was established separately from the all-white Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

From 1860 to 1866, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (later known as the United Methodist Church) was losing its Black membership. Most of the denomination’s Black members left to join the African Methodist Episcopal Church or the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion where they were free to worship as they saw fit.

George Foster Pierce, former president of Emory University and leader of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. George Foster Pierce Papers, 1872-1875, Manuscript Collection No. 85, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

To remedy the continuing loss in Black membership, in 1866 the Methodist Episcopal Church, South began to organize its Black members into an independent church. In 1868, Bishop George F. Pierce, the leader of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, invited affiliated Black preachers and laity to gather for a conference at Trinity Church in Augusta, Georgia. At the conference, about 60 Black preachers became full members of the conference, and deacons’ orders were given to most of the preachers present. In the fall of 1869, the Colored Conference of Georgia assembled in Macon, Georgia.

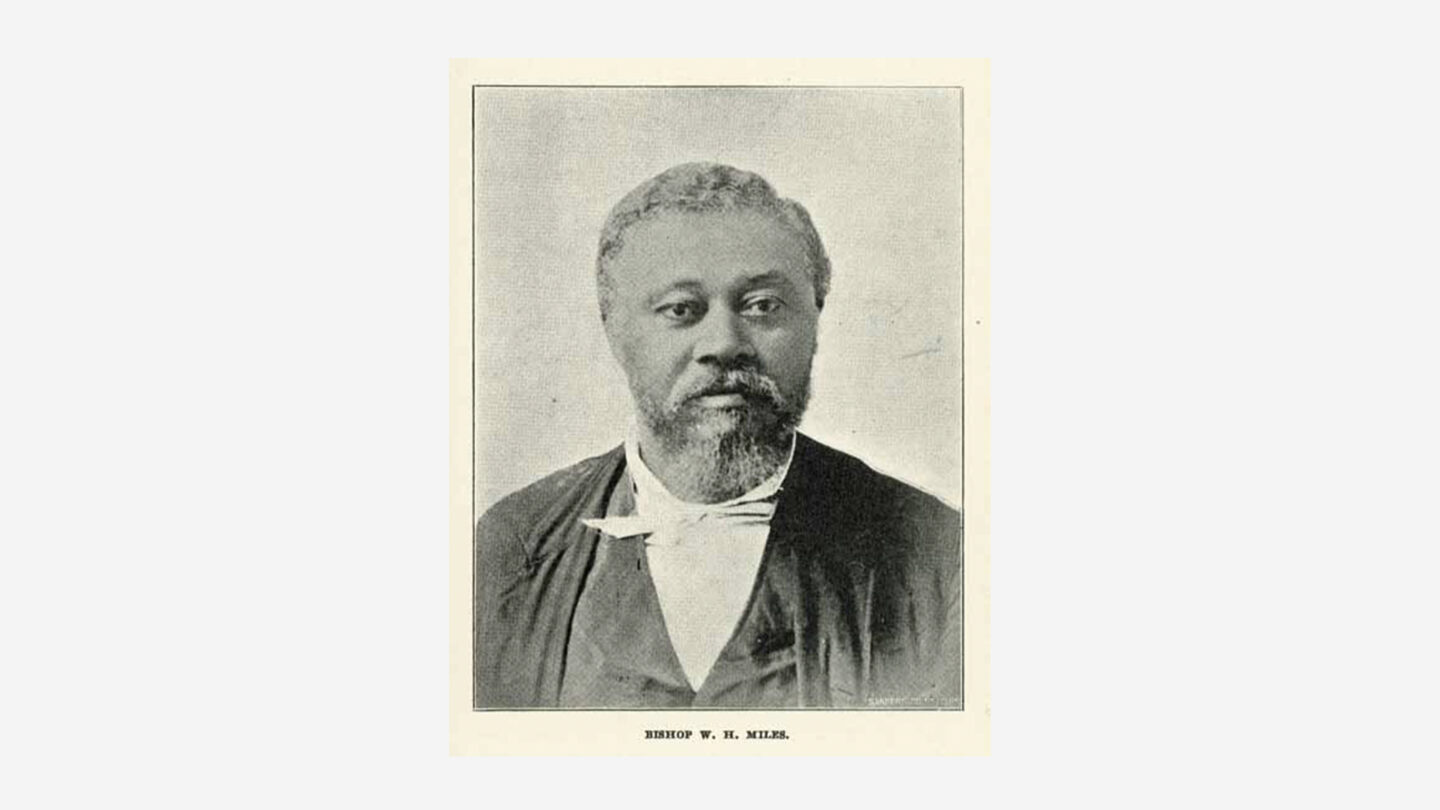

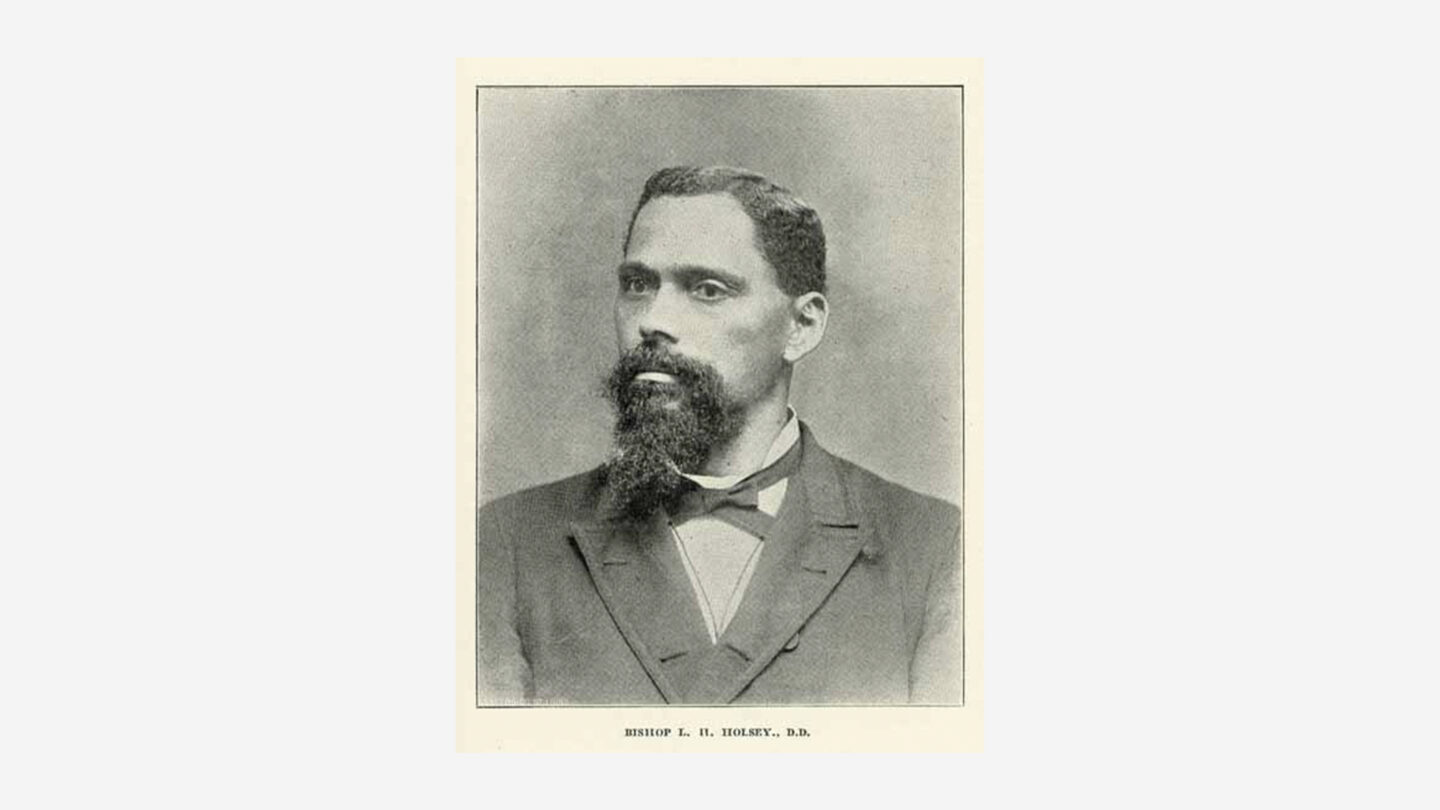

In 1870, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in Jackson, Tennessee. At the founding convention, bishops from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South consecrated William Henry Miles and Richard H. Vanderhorst as the first bishops of the new CME Church. The CME Church was the first African American denomination established in the South. Of the 41 delegates present at the church’s founding, eight represented the Georgia Colored Conference, including pastors Isaac H. Anderson, Lucius H. Holsey, Vanderhorst, and Edward West. After the church was established, the episcopal district of Georgia was active under the leadership of Bishop Miles, and Bishop Holsey was responsible for creating churches and adding members.

The History of the CME Church in Atlanta

The success and rapid growth of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Atlanta can be contributed to Bishop Holsey, who was a dominant force in the church’s direction across Georgia and Atlanta. After serving as a pastor at Trinity CME Church in Augusta and being elected bishop, he moved to Atlanta. He resided in a home on Auburn Avenue near “Bishops Row,” a collection of houses occupied by African American bishops.

Holsey spearheaded the establishment of Atlanta’s first CME churches on the east and west side of Atlanta: Butler Street CME and West Mitchell Street CME churches.

West Mitchell Street CME Church. Terry Kearns, Flickr.

Reverend S.E. Poe founded the Butler Street CME church in 1882 in the old Fourth Ward community. It was organized on property donated by the John L. Grant estate. Church members commissioned a wooden frame structure that was eventually be replaced by a modern brick structure in the 1920s.

Also in 1882, near the old railroad viaduct on West Mitchell Street, the West Mitchell Street CME Church was established. Soon after, the church relocated to a corner property directly across from Atlanta University. The church would see the likes of Lucy Craft Laney, James Weldon Johnson, and W.E.B. DuBois from its front steps.

Name Change

In 1954 at the 23rd General Conference of the church in Memphis, the conference received a recommendation from Channing H. Tobias, a lifelong CME member and the one-time senior secretary of the Colored Work Department of the YMCA. At the time of the 1954 conference, Tobias was chairman of the board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Tobias, along with a committee, suggested renaming the church from “colored to Christian” to remove the color and racial designation. The measure was adopted on May 20, 1954, the same day the Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs. Board of Education. The name change was met with mixed enthusiasm throughout the denomination. Some believed that the name change made the church lose its identity, while others thought it created a more inviting name for its future.

Civil Rights Movement

Atlanta CME churches and their leaders were incredibly enthusiastic about the civil rights of their people. Bishop Joseph A. Johnson, a CME minister and theologian who taught at the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, explored the relationship between the Black church and social activism in his writings. Reverend Robert S. Shorts, the presiding elder of the CME Church, joined Reverend Williams Holmes Borders and other African American pastors in Atlanta in the Triple L Movement (Life, Liberty, and Love) to integrate the Atlanta bus transit system. Butler Street and West Mitchell Street churches opened their facilities for civil rights meetings and organization sessions. West Mitchell served as the meeting place for the Atlanta branch of the NAACP. Professor Charles Lincoln Harper, Geneva Haugabrooks, attorney A.T. Walden, and other NAACP officers provided stellar leadership and planning from the halls of West Mitchell CME Church.

Influential CME

Many movers and shakers from the Black community in Atlanta have come out of the CME Church in Atlanta.

Tiger Flowers, Middleweight Champion, 1926, Topps Ringside card #42, Brooklyn: Topps Chewing Gum Company, 1951. Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tiger Flowers

Renowned middleweight boxing champion Theodore “Tiger” Flowers was a member of Butler Street CME Church. A native of Camilla, Georgia, Flowers joined Butler Street after he moved to Atlanta in the 1920s. By his death in 1927, he was one of the wealthiest men in Atlanta, residing in a palatial mansion on Simpson Road. Known for his gentle demeanor, Flowers was a philanthropist giving generously to his church. Though he did not attend college, he valued education, so he also gave to Morehouse and Morris Brown colleges. A street in northwest Atlanta and a historical marker are all that remain of the legacy of Tiger Flowers.

Dr. Benjamin Mays with Sadie Mays, circa 1980. Hugh M. Gloster Photograph Collection, Morehouse College, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, Archives Research Center

Sadie Gray Mays

What would become the Sadie Gray Mays Nursing home was established at West Mitchell CME Church. An interdenominational committee was established for the purpose of providing more effective care for the sick and homeless. On January 21, 1947, a nonprofit corporation, the Atlanta Association for Convalescent Aged Persons, was founded. West Mitchell member Sadie Gray Mays was elected as its president. Sadie Gray Mays was born in Gray, Georgia, and later married Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays, who became president of Morehouse. Though Dr. Mays was an ordained Baptist preacher, Mrs. Mays joined West Mitchell Street CME Church, where she was a very active member.

In March 1947, the Old Battle Hill Sanatorium site was selected to be used as the nursing home. The home was named “Happy Haven,” and on March 24, 1947, it accepted its first residents. The original home could accommodate up to 60 patients. West Mitchell Street was the meeting place for the Committee to Help the Aged.

A facility renovation was completed at the end of the summer of 1967, which increased its occupancy to 160 beds. On February 8, 1968, the first residents were admitted into their new home. By the end of March, the remaining Fulton County Alms House residents were transferred to Happy Haven, officially closing the county’s “poor house” that had served the Black community. This transfer of residents marked the end of an era of deprivation for the homeless, chronically ill, and unwanted. In 1969, Happy Haven was renamed the Sadie Mays Nursing Home in honor of Mays, who died at the facility on October 10, 1969. It is currently known as the Sadie G. Mays Health and Rehabilitation Center. West Mitchell CME Church was proud of this honor for its most noted member.

Ruby Doris Smith Robinson and son Kenneth Toure Robinson, circa 1965. Mary Ann Smith Wilson, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson Collection on Student Activism, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, Archives Research Center.

Ruby Doris Smith Robinson

Another noted lifelong CME follower and a member of West Mitchell Street CME Church was Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson. Robinson was born in Atlanta on April 25, 1942. The second oldest of seven children born to Alice and John T. Smith, Robinson was raised in Atlanta’s Black middle-class neighborhood of Summerhill. She graduated from Price High School in 1958 and earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Spelman College in 1965. Robinson’s exposure to racial discrimination here in Atlanta, the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-ins in February 1960 all influenced her to become involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

In April 1960, Robinson attended a mass meeting for college students at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. At this meeting and under the guidance of Southern Christian Leadership Conference representative Ella Baker, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded. Robinson was designated a SNCC field representative and assisted in organizing chapters in Charleston, South Carolina, Nashville, Tennessee, and Macomb, Mississippi.

Robinson was involved in SNCC-sponsored community organizing and voter registration drives. She was also involved in Freedom Rides, integrated bus rides that attempted to challenge segregation on interstate buses and at bus terminals. In 1961 she joined a Freedom Ride from Nashville, Tennessee, to Montgomery, Alabama. When Robinson’s bus arrived in Montgomery, a white mob assaulted her and fellow bus passengers. Due to her activism, Robinson was arrested many times, most notably in Jackson, Mississippi, where she spent 45 days in Mississippi state prison.

In May 1966, Robinson replaced James Forman as SNCC’s executive secretary, the first and only woman to serve in that capacity. The following year Robinson was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She died on October 7, 1967, at the age of 25. Her funeral was held at the West Mitchell Street church, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was in attendance along with active SNCC leaders, including John Lewis, Julian Bond, and Stokely Carmichael.

Attorney Donald L. Hollowell, circa 1985. Interdenominational Theological Center Audio Visual Collection, Interdenominational Theological Center, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, Archives Research Center.

And Many More

Community leaders George and Ida Prather participated in providing a place for youth and young adults to have a summer camp. They were members of West Mitchell Street Church. Civil rights lawyer Donald L. Hollowell belonged to Butler Street CME Church. His work as Dr. Martin Luther King’s attorney and mentor to Vernon Jordan ranks him as one of Atlanta’s premier legal minds.

Fulton County Commissioner Emma Ione Darnell, a distinguished attorney, was described as fierce and fearless as an advocate for the marginalized and was an outspoken advocate against Atlanta corruption and politics. A daughter of the parsonage, attorney Darnell’s father was the dean of the Phillips School of Theology (the seminary for the CME Church), and her mother was an advocate for activities for the elderly in the community. The Harriett G. Darnell Center Senior Multipurpose Facility in southwest Atlanta bears her name.

CME Today

Since its historic founding in Jackson, Tennessee, the CME church become one of the premier Christian denominations for African Americans with leading “colored preachers.” Today there are more than 330 churches that comprise the CME Church in Georgia. Other CME churches in the metropolitan Atlanta area include West Side Community, Holsey Temple, Shy Temple, and Greater Hopewell in Atlanta’s Mechanicsville community. Georgia has been blessed to have had many of the noted and stalwart Episcopal church leaders serving as the presiding prelate. The people of the church are faithful and loyal. As Barbara Jackson often says, “Glad to be CME.”