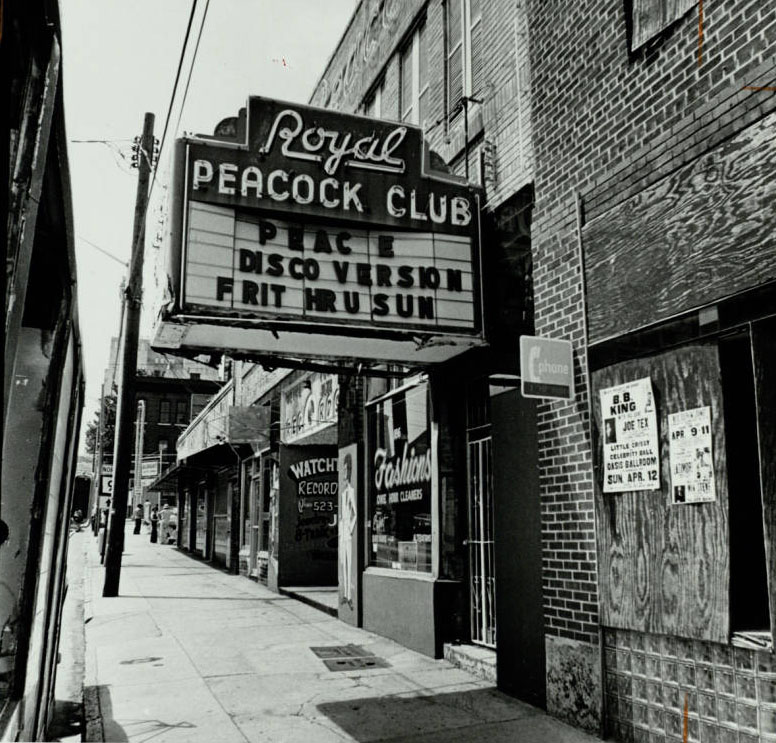

The Royal Peacock. Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator. 126-255 Auburn Avenue Commercial Buildings, Auburn Avenue, Atlanta, Fulton County, GA. Atlanta Fulton County Georgia, 1933. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/ga0211/

“Then there was the Royal Peacock. Let me tell you, that was as hot as it could get!”

Editor’s note: This is the first in a five-part series of articles by Herman “Skip” Mason about Black history in Atlanta.

Long before Atlanta came to prominence as the capital of hip-hop and earned the nickname, “the new Motown,” Atlanta was a hotbed of entertainment, business, and civic life for African Americans. Atlanta boasted of excellent colleges, a thriving social environment, and an entertainment scene that rivaled that of much larger cities. From Auburn Avenue, the hub of the city’s African American activity, Atlanta was ablaze with a cavalcade of the best entertainers who had traveled the “Chitlin Circuit” to Atlanta to perform on its many stages. Early venues where Black Atlantans went to be entertained included the Roof Garden, City Auditorium, Sunset Casino, Magnolia Ballroom, the Waluhaje, and the Auburn Avenue Casino. However, no venue was as popular in Atlanta as the Royal Peacock.

Carrie Cunningham. AJCP145-014ab, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

The extremely popular Top Hat Club located at 185 Auburn Avenue closed in early 1949. Carrie Cunningham, a local businesswoman and former entertainer with the Silas Green circus, acquired the club for $31,000. Cunningham renamed the club the Royal Peacock. She was a beautiful, stately, well-dressed woman who often stepped out in dazzling jewelry, mink coats, hats, and gorgeous dresses. Her style reverberated throughout the club. Inside, Cunningham decorated the club with a peacock motif due to her love for the exotic bird. Outside, she commissioned a brand-new sign that lit up the block along with the signs at the Savoy Hotel in the Herndon Building and the blue neon “Jesus Saves” sign at Big Bethel A.M.E Church.

According to local lore, Cunningham established the club so her son Red McAllister, a well-known musician and bandleader, could stay out of trouble. She hoped that he would help book acts and manage the club.

Graham Jackson entertains patrons, possibly at the Royal Peacock. Graham Jackson Photographs, VIS 34.21.17, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

McAllister and other Black promoters, such as J. Neal Montgomery, B.B. Beamon, and Henry Wynn, booked great acts for the Royal Peacock. These included James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, Dinah Washington, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Glady Knight and the Pips, Patti Labelle and the Bluebelles, Ike and Tina Turner, the Supremes, the Temptations, and Marvin Gaye. Local musicians Billy Wright, Zilla Mays, Lavern Baker, and others also performed. Comedians Timmie Rogers and Mantan Moreland were a significant part of the club’s entertainment that also included a floor show with peacock dancers, a house band, and legendary master of ceremonies Gorgeous George.

John B. Smith Sr., the former CEO of the Atlanta Inquirer, described the Royal Peacock as “something like the Cotton Club in New York or the Apollo.”

Royal Peacock poster advertising Aretha Franklin, 1966. Courtesy Atlanta Bands via Facebook

Performances at the club were advertised with colorful posters (printed by Southern Poster Company) plastered on poles throughout the city, the local Black-owned radio station, WERD, and newspapers, such as the Atlanta Daily World and Atlanta Inquirer. Those methods of advertising, along with word of mouth, led to enormous crowds at the Royal Peacock. Many acts had to do two shows a night to accommodate the demand.

B.B. Beamon said he loved it when shows were sold out.

“They didn’t have anywhere else to go … so you felt like you were doing a service for the people. That’s the part that I enjoyed most.”

During the club’s heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, celebrities often visited. Noted athletes, including Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis, enjoyed the club as did civil rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr., Hosea Williams, and Andrew Young. Cunningham sometimes hosted lavish banquets for these distinguished guests. She also put them up, if necessary, at the Royal Hotel, which she also owned.

In addition to hosting great live entertainment, the Royal Peacock was available as a rental venue, and fraternities, sororities, other local organizations, and Atlanta’s Black elite social clubs, had anniversary dances, Sweet 16 parties, and Christmas events at the spot. The club also hosted many fundraisers for the Boy Scouts, the Waiter’s Union, and other organizations to benefit the local community.

Advertisement in the Atlanta Inquirer featuring the Royal Peacock. Atlanta Inquirer, Vol. 1, No. 35

In 1959, Henry Wynn acquired the Royal Peacock. Wynn was the owner of Supersonic Attractions and had a stellar roster of entertainers. Local entrepreneur Q.P. Jones managed the club. Jones also owned the Auburn Casino across the street from the Royal Peacock.

By the 1970s, the Royal Peacock’s popularity waned with integration (it was no longer one of the only venues where Blacks could see live entertainment) and the shifting of the Black community to the westside of Atlanta. Other factors that eventually contributed to its decline included a lack of parking (as people were acquiring more automobiles in the 1960s) and nighttime crime.

The Royal Peacock billboard during the disco era. AJCP145-014bj, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

The Royal Peacock languished during the disco era, becoming first a site for a theatrical group, then the Men of Styles club, and eventually a reggae club.

Though Cunningham died in 1973, the club she established was indeed Atlanta’s “Club Beautiful,” and it helped create the fertile soil that allowed Atlanta to become the hip-hop and rhythm and blues capital of the South.

About the Author

Herman “Skip” Mason Jr. is a local pastor, archivist, historian, and author of African-American Entertainment in Atlanta.