View of rowers on the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta circa 1995. Cotton Alston photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Atlanta History Center partnered in 2021 with the Trust for Public Land to commemorate their 30th anniversary with an onsite display in the Don and Neva Dixon Rountree Visual Vault about the history of the Chattahoochee River. The Trust for Public Land has protected more than 3.3 million acres and completed more than 5,400 park and conservation projects.

History of the Chattahoochee River

The name of the Chattahoochee River comes from the Muscogee language. Cato-hocce hvcce —marked-rock river—derives from cvto “rock,” hocce “marked,” and hvcce “stream.” The term refers to rock outcroppings along the upper portion of the river running through the geology of the Georgia Piedmont-including the Atlanta Metro area.

The Chattahoochee River rises from a small, cold-water spring in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains in the far reaches of northeast Georgia. From nearly 3,200 feet above sea level, it merges with other springs and surface water flowing south as its course runs more than 430 miles, stretching the length of the state. Atlanta currently gets 70% of its drinking water from the river for more than 5 million people.

Atlanta History Museum’s Visual Vault display features artifacts and archival items related to the history of the Chattahoochee River. Spanning from indigenous life to current uses, the display highlights artifacts and archival materials that show the diversity and use of the Chattahoochee River over the course of human habitation. Below are just a few topics and artifacts featured in the exhibition.

Indigenous people inhabited Georgia and the Chattahoochee River basin for thousands of years.

Indigenous Life

The most culturally significant time period was the Mississippian Period for nearly 800 years into the 1600s. Primarily farmers, Mississippian people lived in riverside communities that often featured mounds. The increasing presence of Europeans added to the collapse of the Mississippian Culture through disease, enslavement, violence, and disruption of the culture’s political and commercial structure. Surviving populations formed new cultural associations as the Muscogee and Cherokee native groups throughout the Southeast. The Chattahoochee River played an integral role in their lives and, after 1755, acted as a boundary between the Muscogee and Cherokee Nations in North Georgia. By 1827, whites had driven the Muscogee people out of Georgia. The Chattahoochee, however, remained as a border between the state’s white settlement and the Cherokee Nation, with its capital at New Echota, only 60 miles north of the river. While some Indigenous people moved toward commercial agriculture, many used undeveloped land for hunting, which whites perceived as a failure to use the land’s full potential. As a result, Indigenous territories were obtained through various means, including a series of government-mandated treaty cessions. By the end of 1827—only 88 years after the first treaty—all Muscogee lands within the state of Georgia had been lost to white settlers.

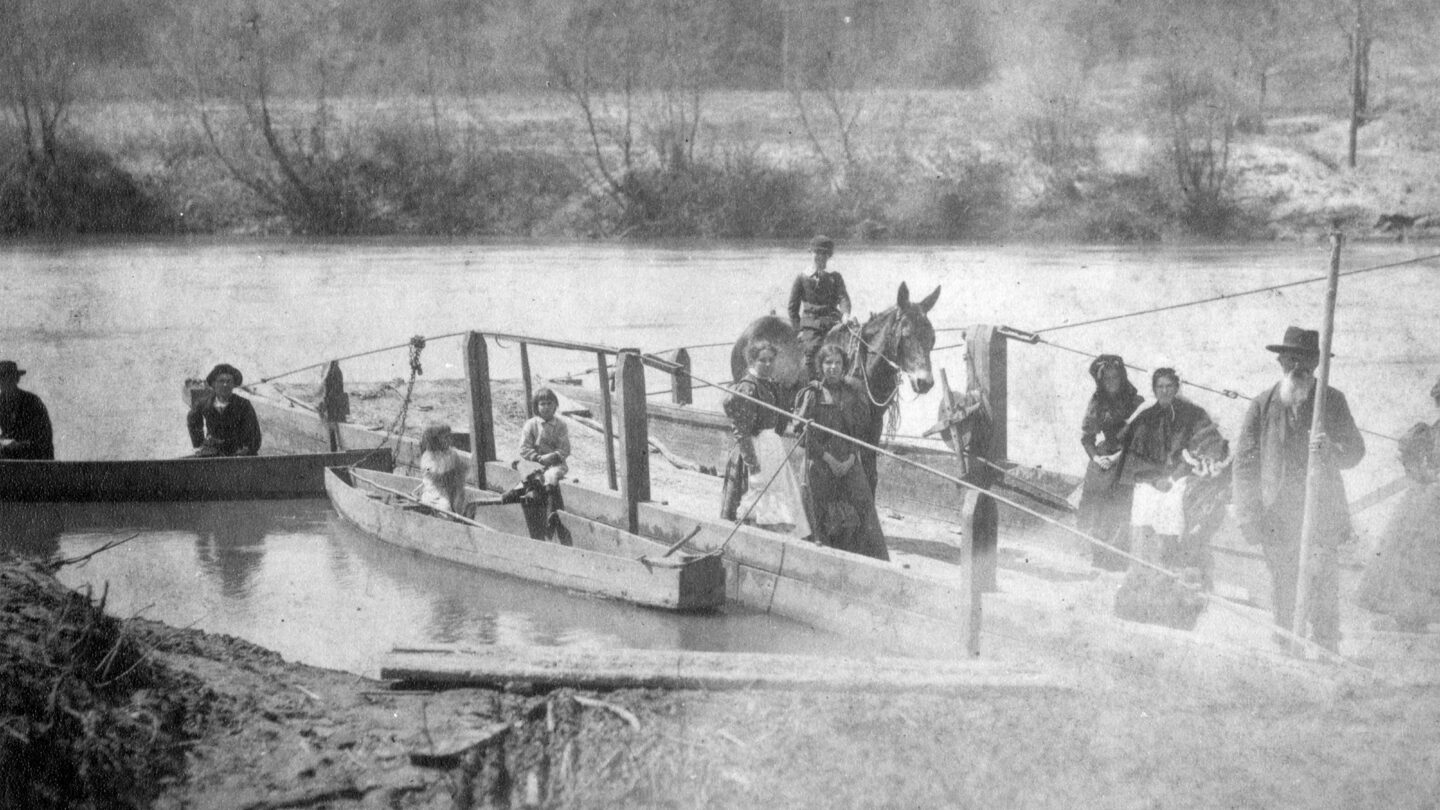

View of Mayson-Turner Ferry on the Chattahoochee River in Cobb County with Calhoun “Uncle Coat” Turner as ferryman, 1903. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, VIS 170, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

River Ferries

The Mayson-Turner Ferry, now Veterans Memorial Highway, was established in 1844 by James Mayson and Daniel Turner and operated through 1897. A series of privately owned river ferries allowed for the movement of livestock, people, and goods across the river, connecting businesses to settlements throughout the state and beyond. The use of ferries tapered off by the late 1950s due to the construction of bridges and the growth of the state highway system. The legacy of those ferries lives on through street names throughout the area, including Paces Ferry Road, Powers Ferry Road, Johnson Ferry Road, Bells Ferry Road, and others. Ironically, Atlanta’s first ferry crossing was located at a site named Shallow Ford.

Water Supply

Atlanta’s population and industry grew in the post-Civil War era as the city promoted itself as the commercial and financial center of a changing Southern economy—the New South. This growth resulted in an increased need for freshwater for city residents and businesses. Subsequently, the Atlanta Water Works Hemphill Avenue Station was completed in 1893 and is still in use by the Department of Watershed Management. To this day, there remain concerns over Atlanta’s water use. As a result of the city and state’s use of so much water from the river, there is a well-known conflict between Georgia, Alabama, and Florida called the “Tri-state water dispute” or the “Water Wars” over equal rights to water and impacts on water use and supply.

In April 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed a Florida lawsuit claiming that Georgia uses too much water, negatively affecting Florida’s oyster industry. Yet the court reminded Georgia that the state is compelled to use basin water reasonably “to help conserve that increasingly scarce resource.” More lawsuits related to water use are still in the court system.

The Chattahoochee River today is used primarily for drinking water and leisure activities.

Recreation

One significant leisure event, the Ramblin’ Raft Race, ran from 1969 to 1980, with a course stretching nearly 10 miles from Morgan Falls Dam to Paces Ferry Road. Established by fraternity members from Georgia Tech, the race attracted thousands annually and was infamously known as “Woodstock on the Water.”

Participants in the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River, 1971. Floyd Jillson photographs, VIS 71, Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

The race was canceled in 1980 because of its property owner complaints, and negative environmental impact–this shortly after the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area (1978) was established, protecting a 48-mile stretch of land along the river.

Wildlife

Historically, the Chattahoochee River was a warm-water stream for most of its length. The completion of the Buford Dam on Lake Lanier in 1956, however, changed the river. Since that time, the dam releases cold water chilled by the depth of the reservoir. As a result, the river is now a cold-water stream south of the dam. Many species thrive in the river’s cooler temperatures. In the Atlanta area, the river maintains a year-round cool temperature, rarely rising above 50°F. It is home to bass, bluegill, catfish, trout and many other species of fish, more than 20 species of freshwater turtles, 37 species of salamanders and eel-like sirens, 30 species of frogs and toads, and alligators further downstream. Due to the cold water released from Lake Lanier and stocking by the Department of Natural Resources, the Chattahoochee is now the nation’s southernmost trout river and is a state-designated trout stream from Buford Dam to Peachtree Creek. Previously, the river was incapable of sustaining trout below the Blue Ridge Mountains.

View of the Chattahoochee Valley Blueway at sunrise. Darcy Kiefel, The Trust for Public Land.

The Trust for Public Land

The Trust for Public Land is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to create parks and protect land for people, ensuring healthy, livable communities for generations to come. Since 1972, the Trust for Public Land has preserved and made accessible land for public use. They’ve completed several projects in Georgia, including the revitalization of Cook Park in partnership with the Vine City community, the purchase and donation of several properties to the National Park Service in the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, and the acquisition of properties to expand the Atlanta BeltLine.

The organization is now working to protect a 100-mile stretch of the Chattahoochee River between Buford Dam and Chattahoochee Bend State Park in Newnan, Georgia. The vision for the project, Chattahoochee River Lands, connects communities to natural resources, protecting the river while making it more accessible.

The Chattahoochee River is an icon of the Atlanta region, identified with the city through popular culture.

Providing resources for nourishment, agriculture, energy, industry, recreation, and other resources, the river is Atlanta’s waterfront. There remains work to be done to protect the Chattahoochee and surrounding areas, yet advocacy organizations including the Trust for Public Land, Friends of the River, Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, Atlanta Regional Commission, and others work through education, legislation, and land purchase to preserve the river. These organizations have made progress in protecting and making accessible one of Georgia’s most important natural resources.