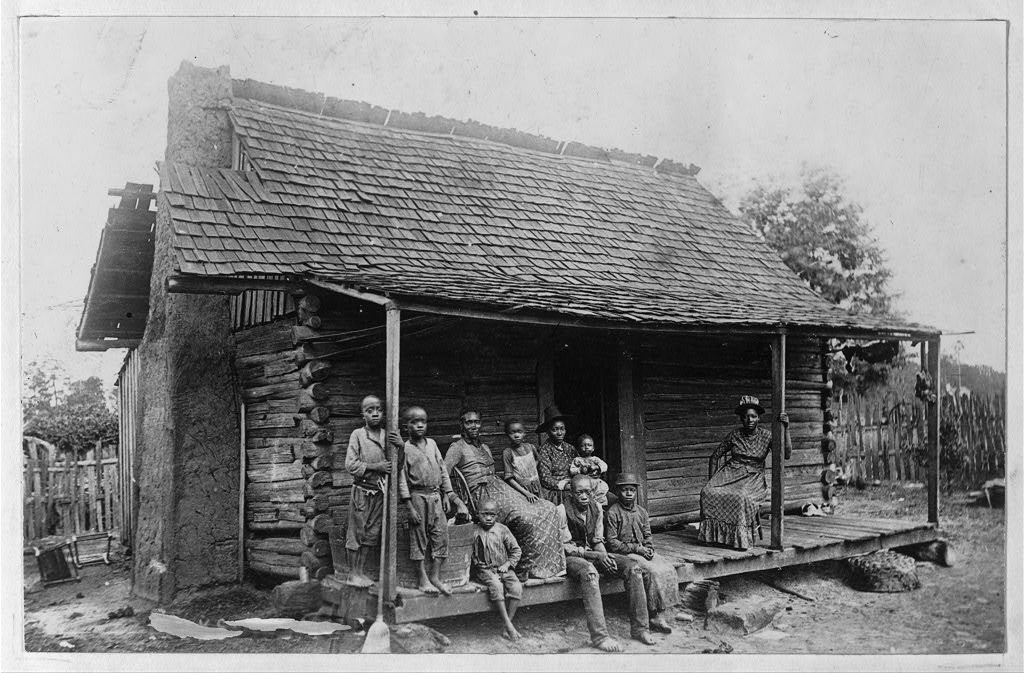

People sitting on the porch of a slave cabin in Barbour County, Alabama (Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

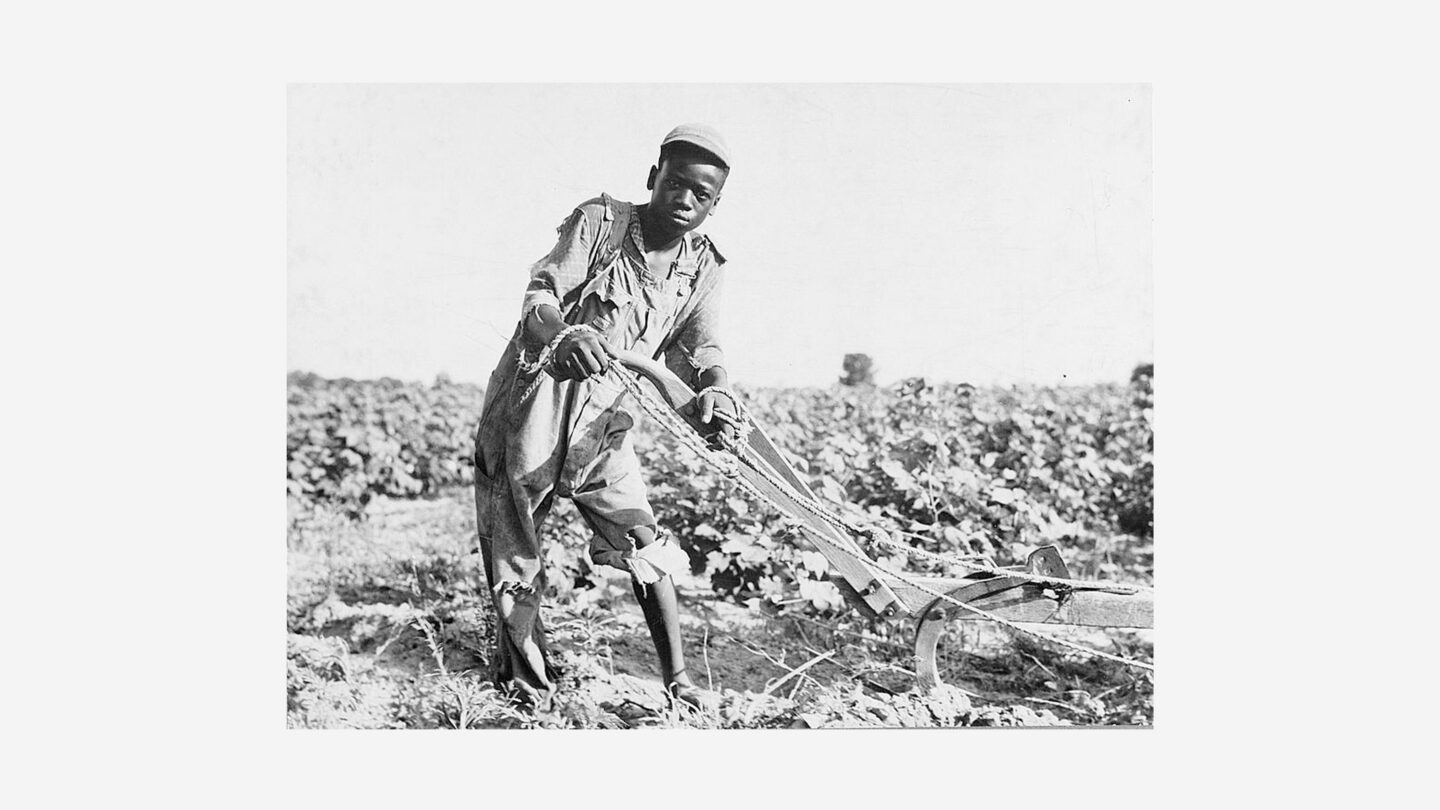

Seventy-one years after the end of the Civil War, the Work Projects Administration embarked on a project to interview formerly enslaved people across the United States. They interviewed over 2,300 individuals who gave firsthand accounts of surviving slavery and being freed, but freedom, what it meant, and how it was allowed to be expressed differed from person to person.

Reconstruction brought its own challenges which complicated the lives of people who had hoped for freedom for over two hundred years. The following accounts of six formerly enslaved persons from Georgia reflect this complex and varied process of freedom.

Minnie Davis

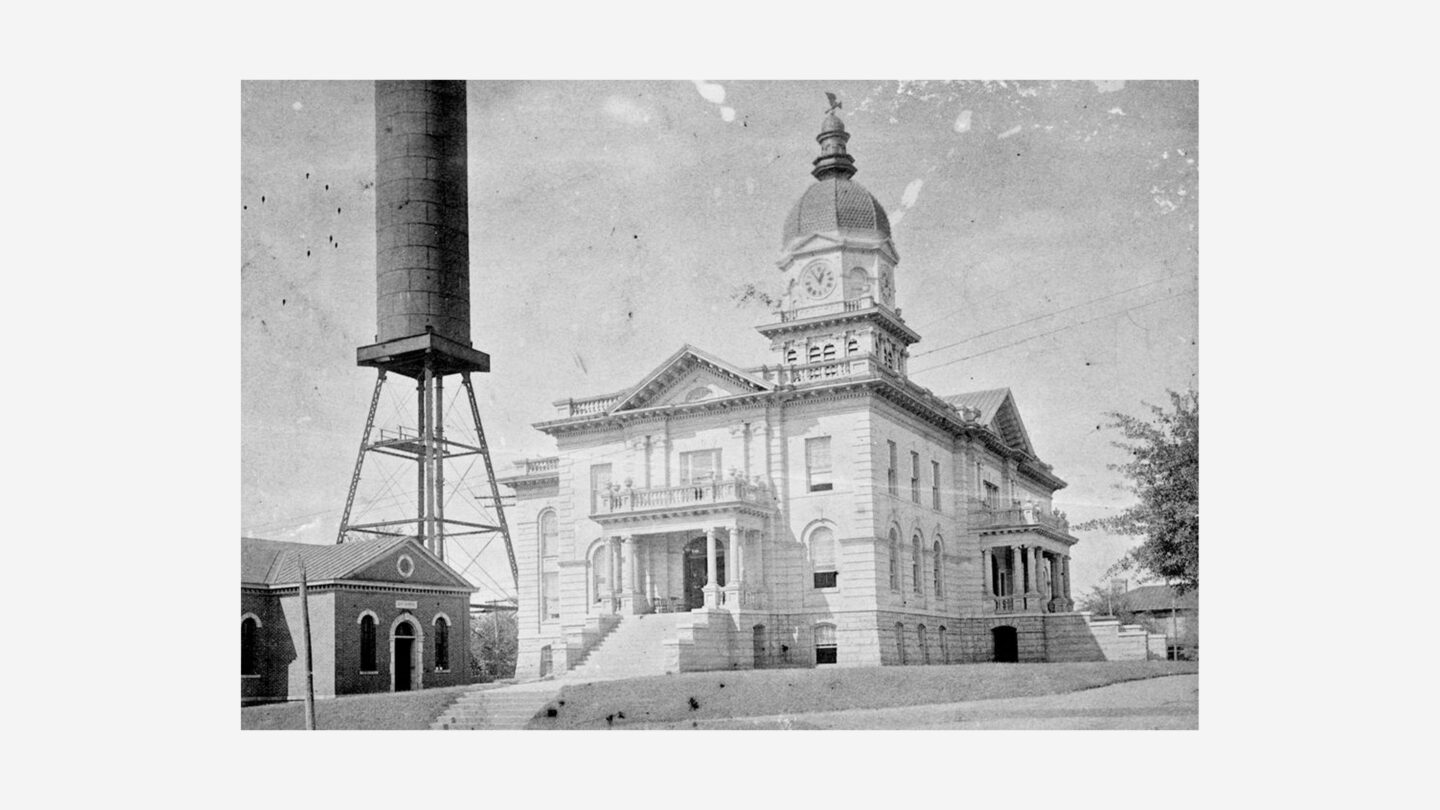

In 1859 in Penfield, Georgia, Aggie Crawford gave birth to a daughter, Minnie. Both mother and daughter were enslaved by John Crawford who moved them to Athens, Georgia where Minnie lived the rest of her life. During the Civil War, Aggie Crawford, who had secretly learned to read and write, stole newspapers to relay updates about the war to other Crawford enslaved. Minnie and her mother attended church every Sunday. During the war, Reverend Hoyt of First Presbyterian Church would pray for God “to drive the Yankees back” while Aggie prayed to herself “Oh, Lord, please send the Yankees on and let them set us free.” Minnie was a child during the war but vividly remembers the day that she and other enslaved people in Athens learned of their freedom. They rushed to the town center and rallied around a liberty flagpole. Enslaved people from around Athens flocked to the town to celebrate the Jubilee.

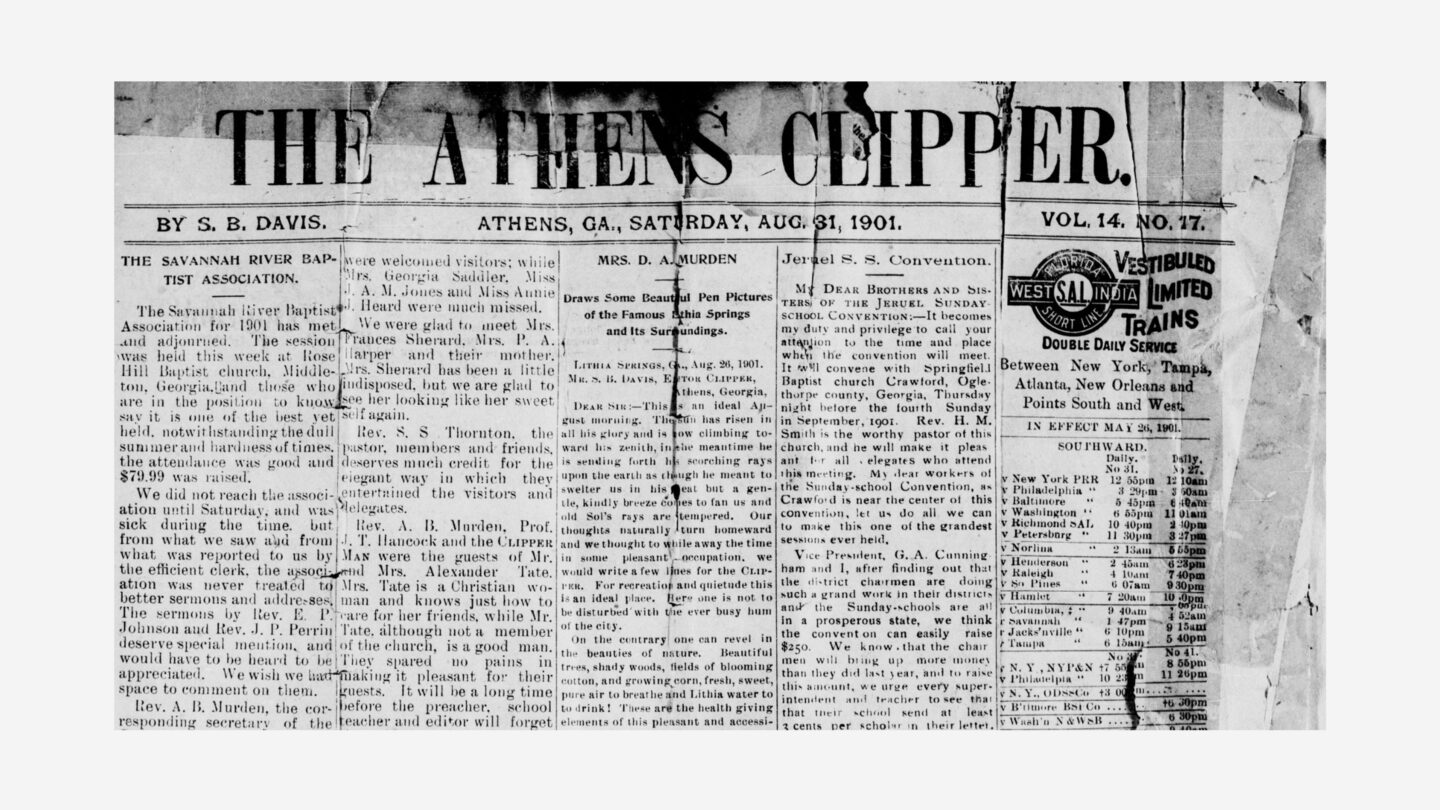

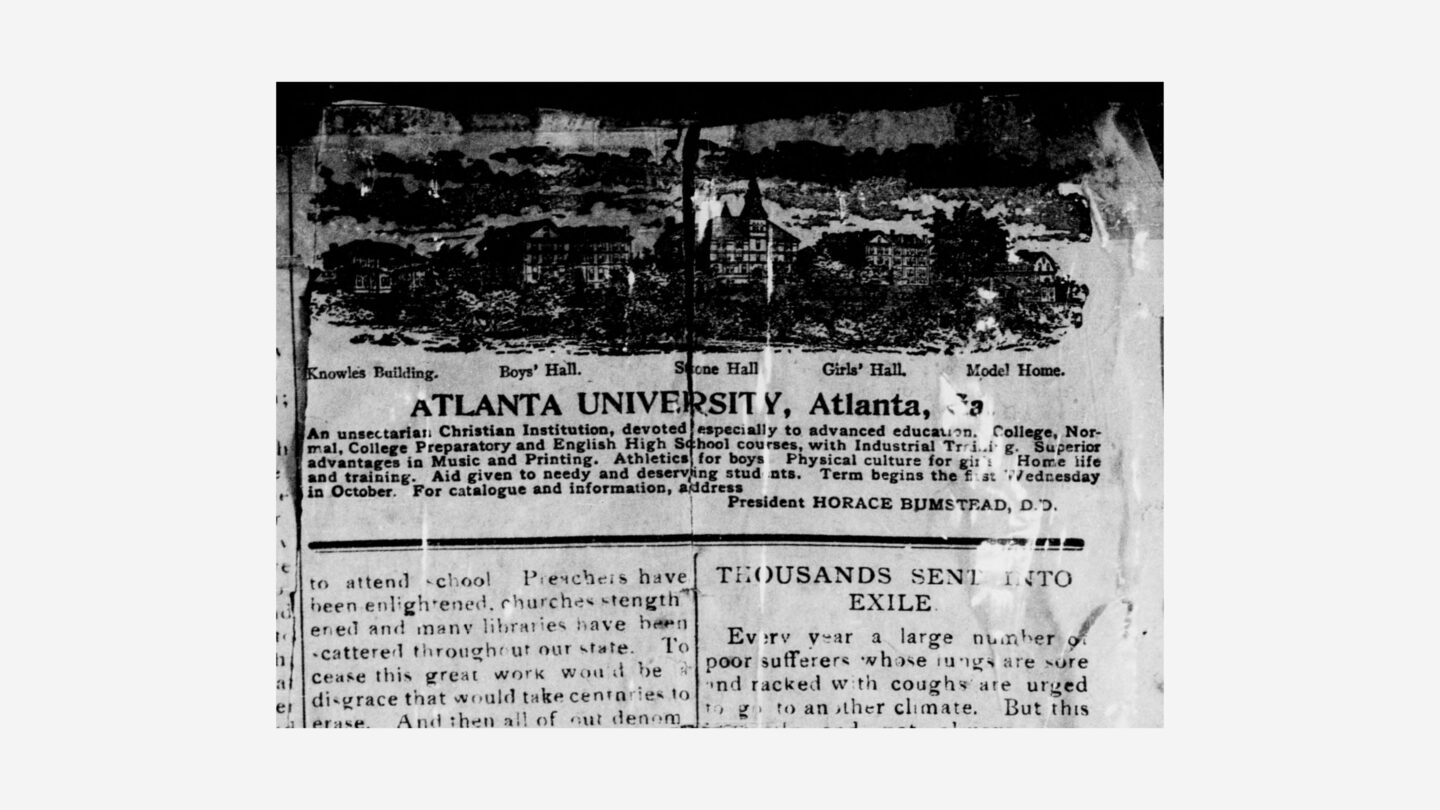

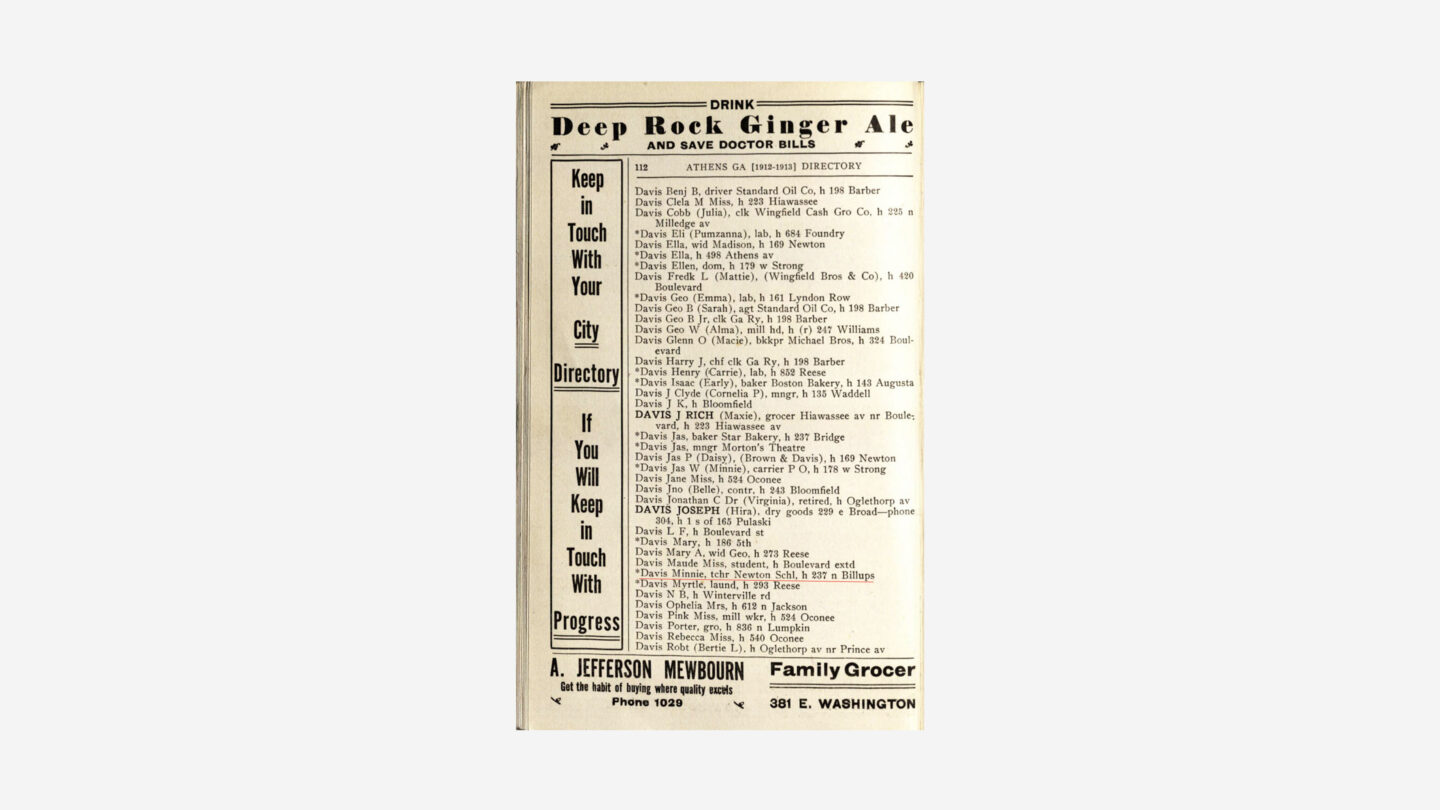

Years after the war, Aggie Crawford bought a home for her and Minnie. Minnie went on to graduate from Knox Institute and Atlanta University returning to Athens to teach for forty years. She married Samuel B. Davis who published the Athens Clipper, a prominent newspaper for the Black community in Athens. After her husband’s death, she continued to publish the paper until she sold it. Minnie Davis retired from teaching due to her declining health and lived out the rest of her days in the home her and her late husband had shared until she passed in 1940.

Benjamin Johnson

Benjamin Johnson accompanied his enslaver, Luke Johnson, while he served in the Confederate army. Enslaved labor was used across the Confederate army for various day-to-day tasks. Like many enslaved men who accompanied those who owned them to war, Benjamin Johnson was responsible for ensuring Luke Johnson returned home whether that be alive or in a casket. While traveling with the Confederate army, Benjamin witnessed the brutal fighting at Richmond attesting to watching soldiers lose their limbs and their lives. Benjamin watched firsthand a war that would decide the fates of him and all other enslaved people in the United States.

Luke Johnson had been “all shot up” by the end of the war, and Benjamin Johnson brought an injured Luke back to his plantation and back to the people he no longer owned. Upon their arrival, Benjamin was crowded by other enslaved people on the plantation eager to know whether they were to be freed. While most enslaved persons learned of their freedom from their former owners, Benjamin Johnson was the person to announce that the war was over, and they were freed.

Lewis Favor

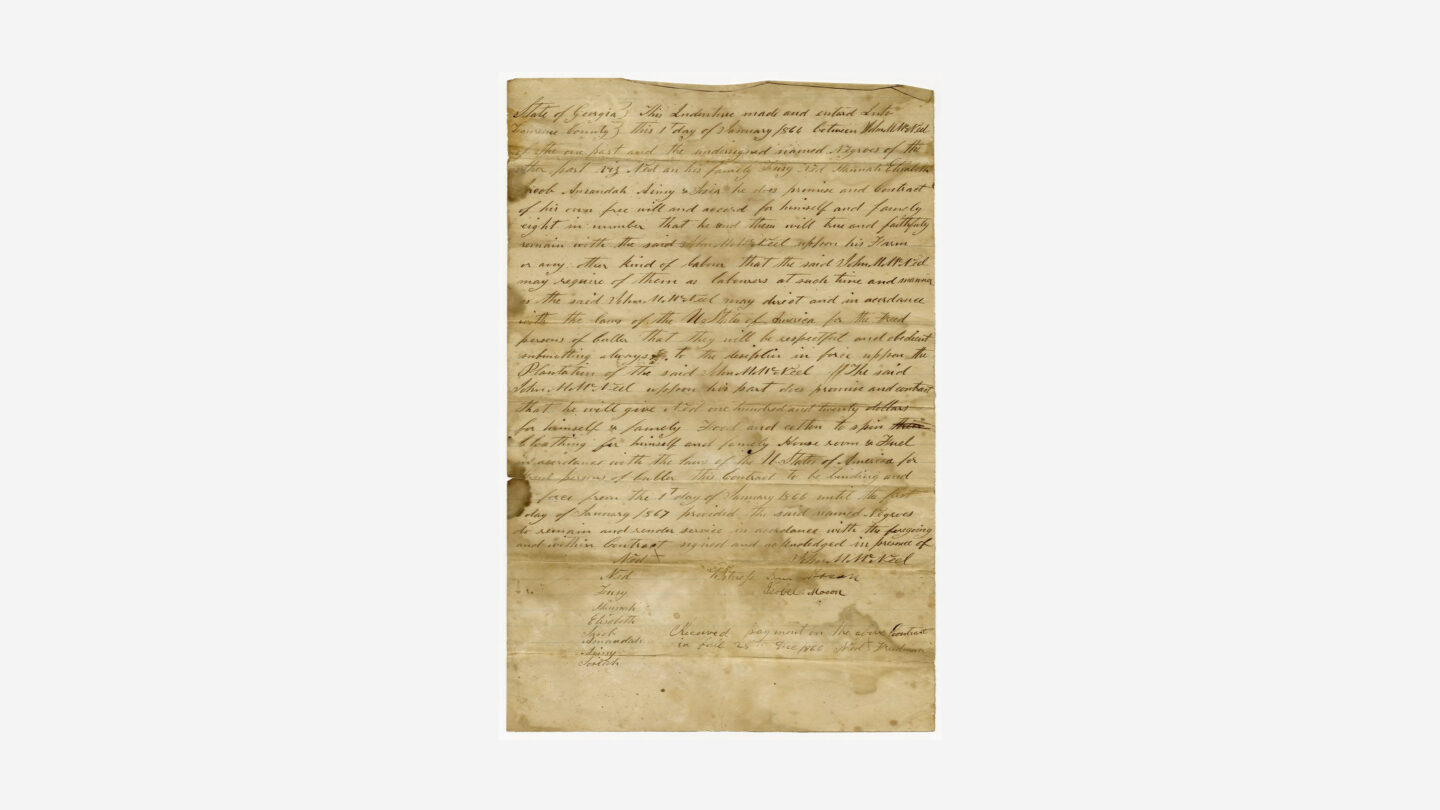

Lewis Favor was born in 1855 near Greenville, Georgia and was enslaved by Mrs. Favors, more commonly referred to as “Widow Favors, ” who Lewis waited on since he was a child. After a battle was fought nearby, Widow Favors fled Greenville and took Lewis, his mother, and a few other enslaved to La Grange, Georgia. Lewis was given the responsibility of holding onto two thousand dollars in gold currency for protection. Widow Favors would intermittently count the gold to ensure all of it was there. Other enslaved of Widow Favors were assigned similar tasks of protecting or burying valuable items from Union soldiers. When Widow Favors announced their freedom Lewis remembered it as a happy day “because he realized then that he could do some of the things that he had always wanted to do.”

However, this was not always the reality for many freedmen. Lewis Favors remembered many difficulties for formerly enslaved individuals after emancipation. Former enslavers gave minimal payment for labor, freedmen were directed on where and how they could walk in the streets, white men would cut the clothes of freedmen who were well dressed, and were accosted by white people who threatened their lives if they didn’t comply with them.

George Womble

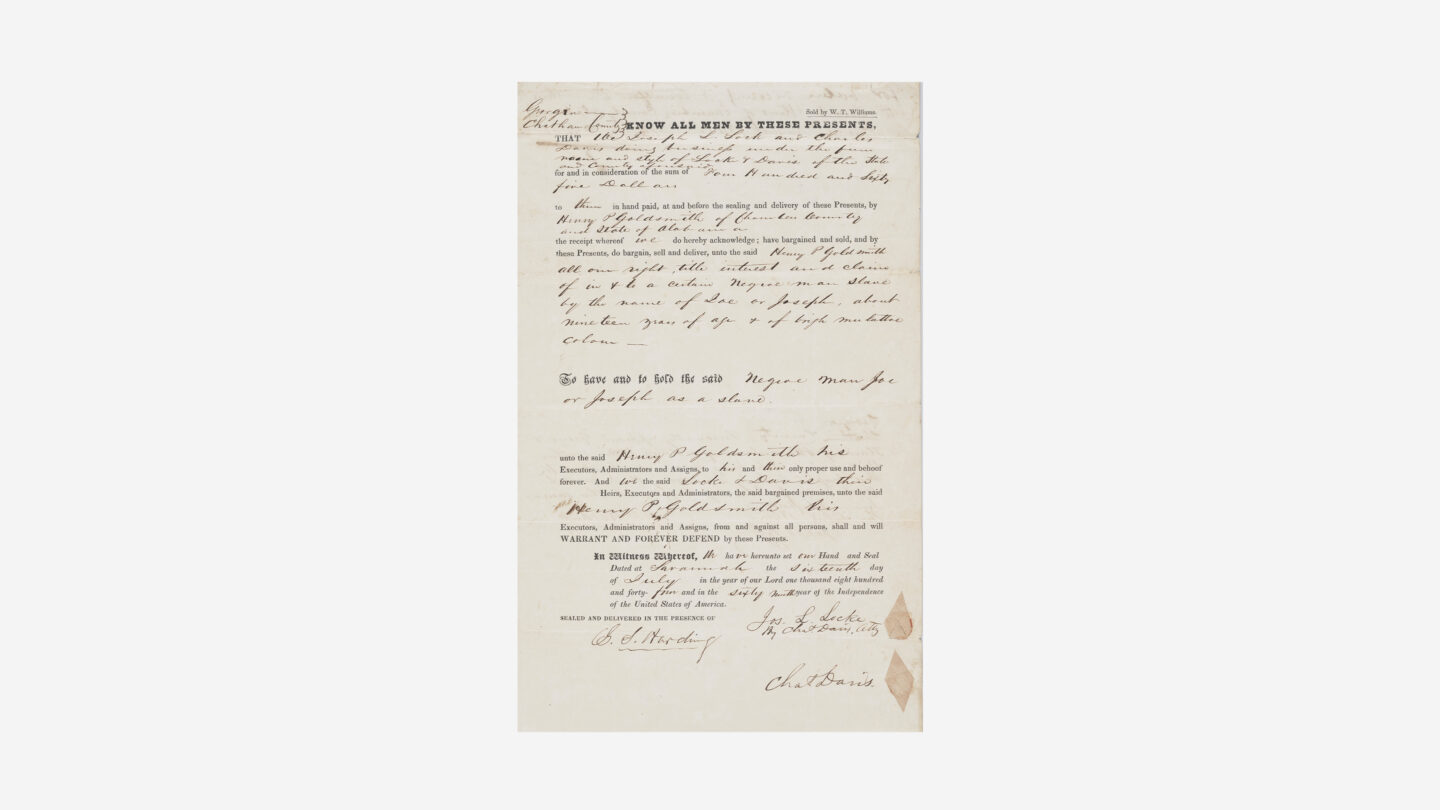

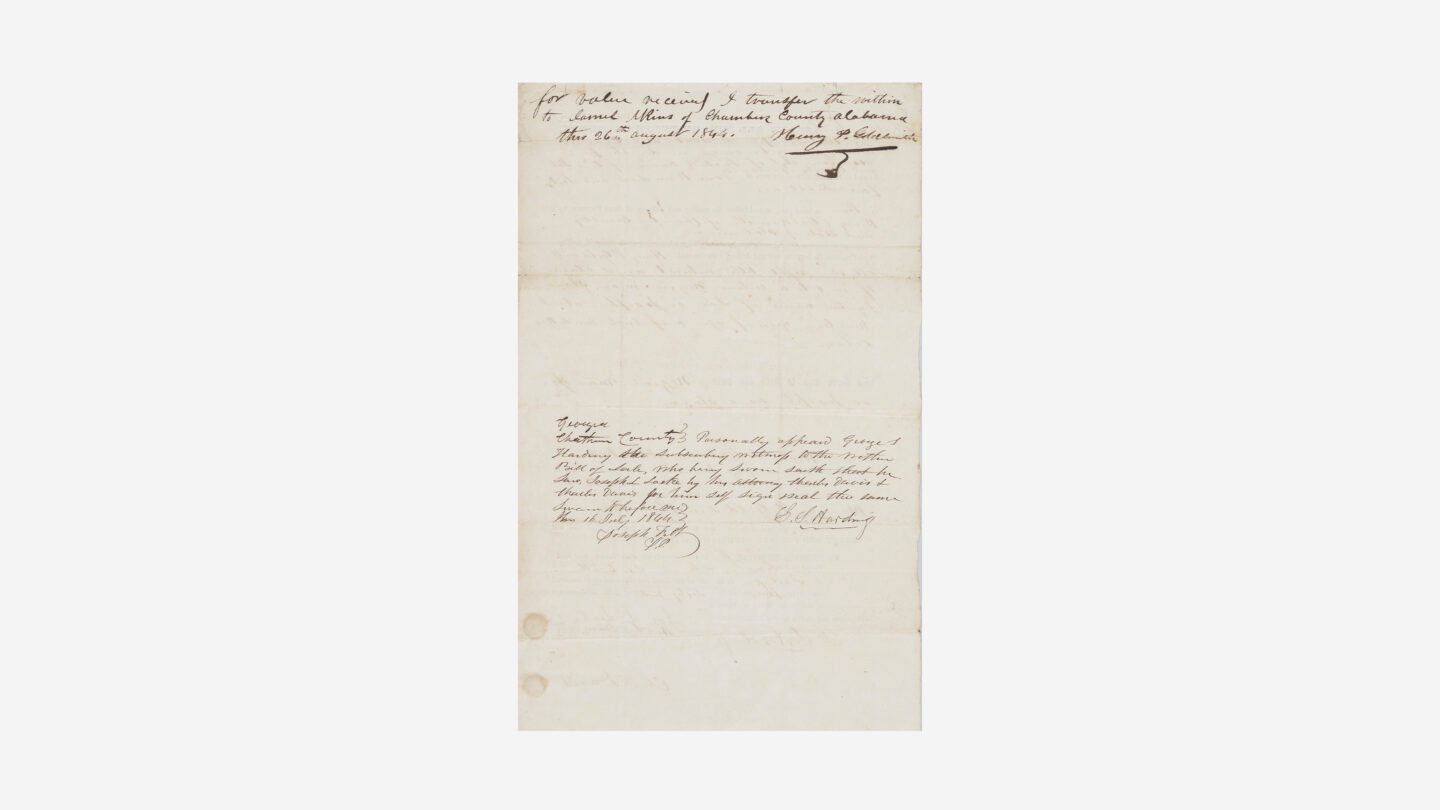

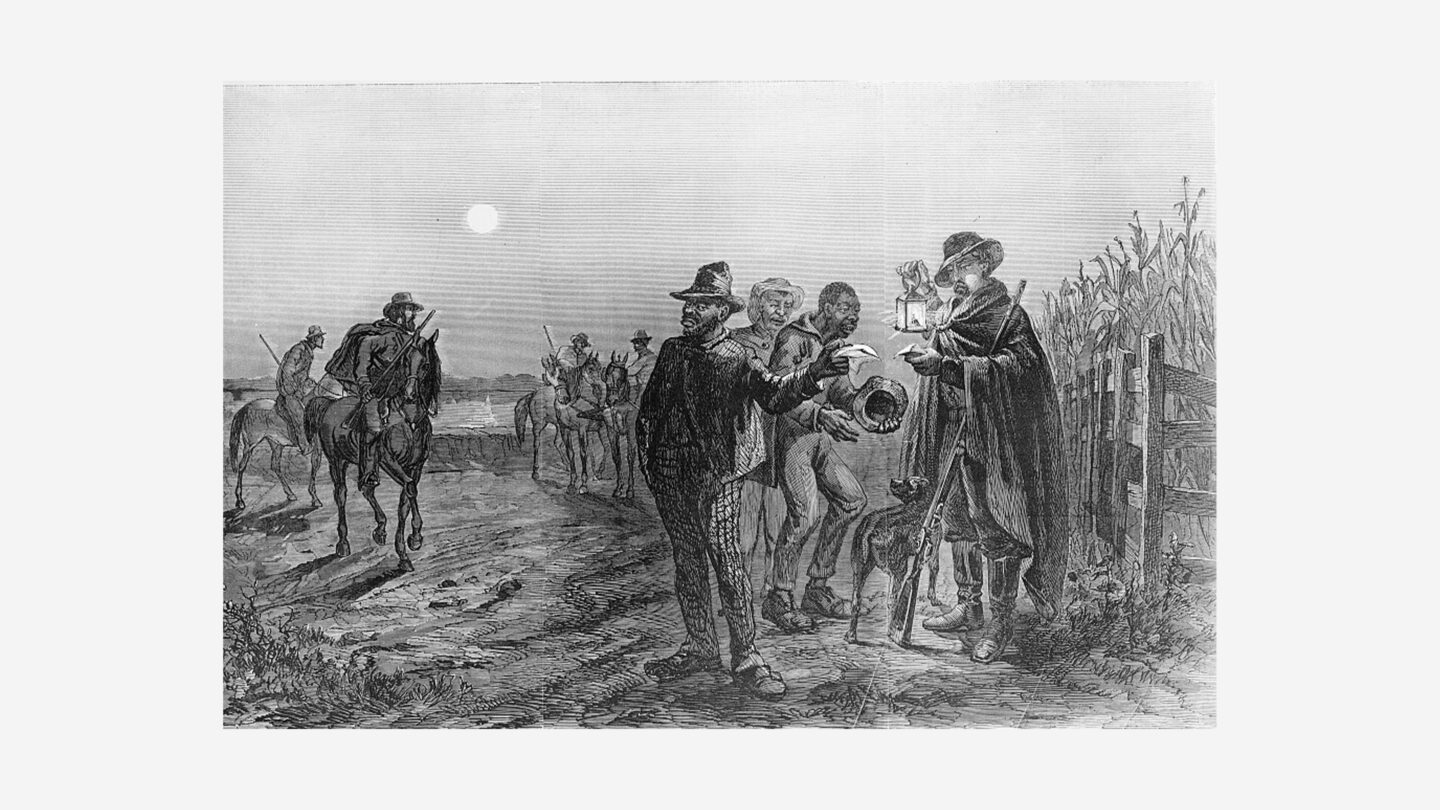

George Womble was born in 1843 in Clinton, Georgia. He was sold twice eventually being owned by Jim Womble of Talbotton, Georgia where he was located during the Civil War. Jim Womble joined the Confederate army declaring he “would wade in blood up to his neck to keep the slaves from being freed.” On the Womble plantation however, George remembered late night secret meetings in the woods where enslaved of the Womble plantation met to sing and pray for freedom. “I knew that someday we’ll be free and if we die before that [time] our children will live to see it.” Union soldiers raided Womble plantation taking all the livestock they could find, tearing up the beds of Jim Womble’s family, and pouring syrup in the mattresses.

The arrival of Union soldiers did not bring freedom to the Womble enslaved as hoped. George was forcibly bound over and kept by the Womble family who refused to release him despite being legally free. At one point, Mrs. Womble helped him escape, but he was later caught. When found, they tied a rope around his neck and made him run back to the plantation as the others watched and rode on horseback. George’s second attempt at escape was successful. He soon established his own blacksmith shop where he made his living for many years. Later he decided to move and settle in Atlanta in his old age.

Adaline Willis

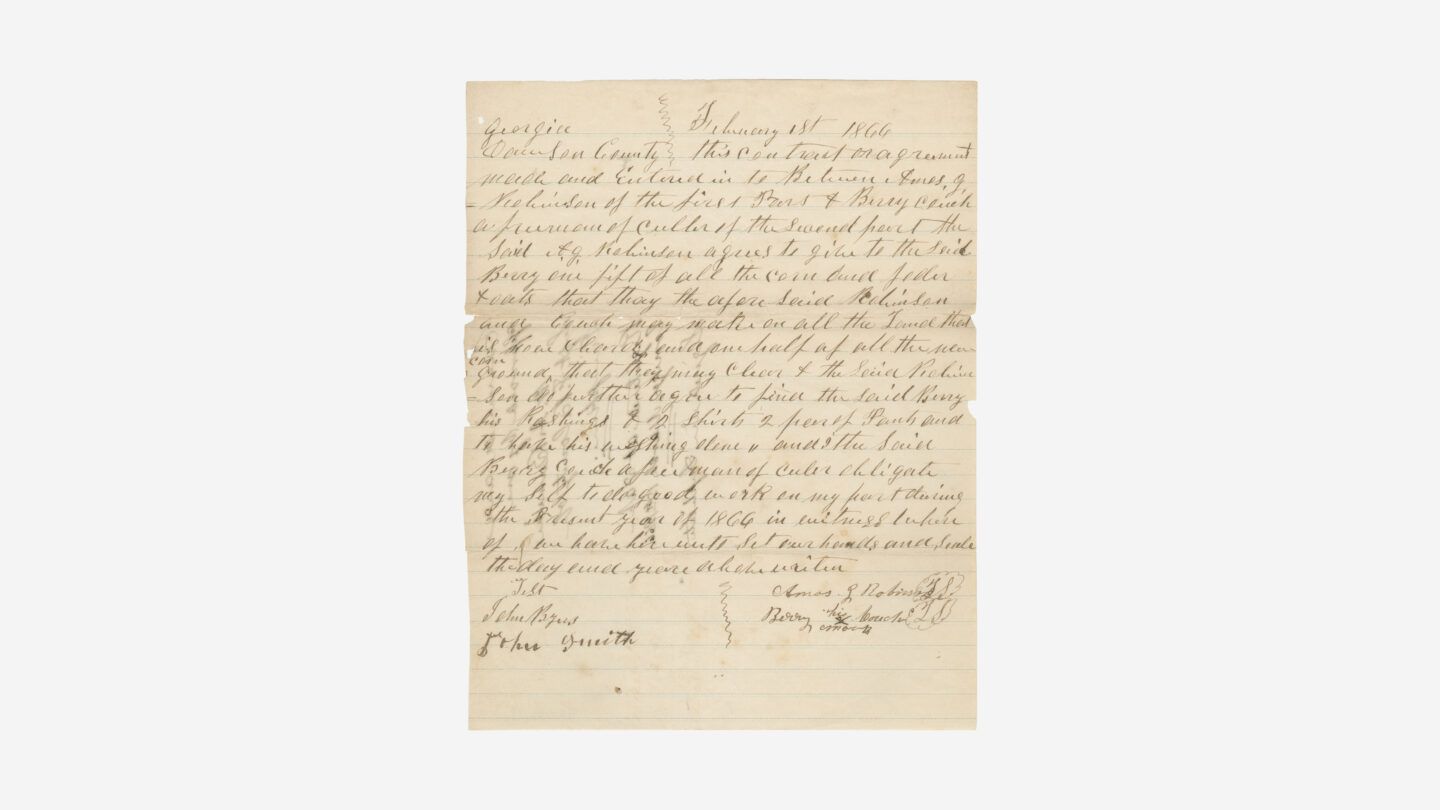

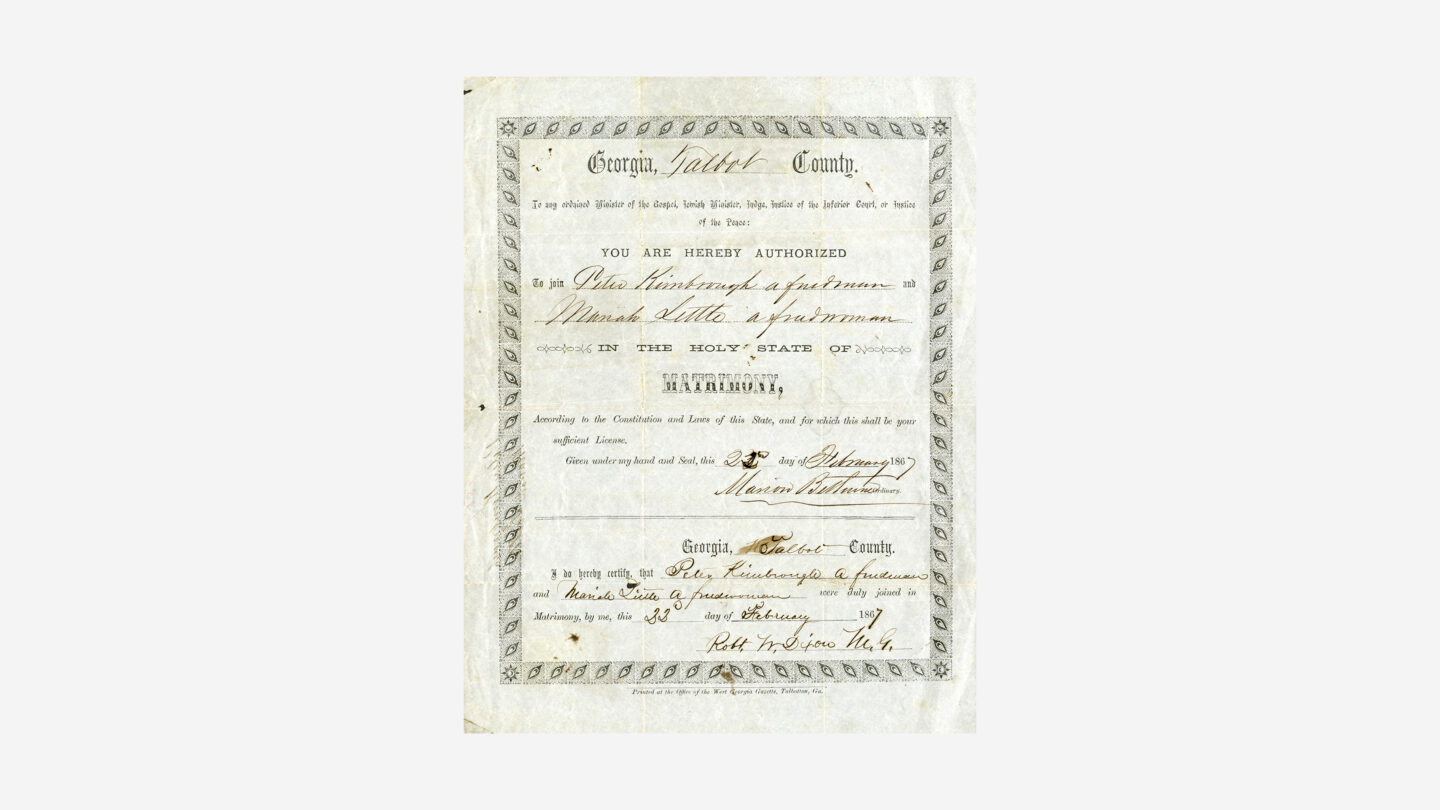

Adaline Willis was born on the Wright plantation in Oglethorpe County around 1835. She was brought to Wilkes County when one of the Wright family’s daughters married William Turner. It was here that she met and married Lewis Willis who was enslaved on a neighboring plantation. To marry, Adaline and Lewis required the permission of both of their enslavers. Once they received permission, William Turner married the two by having them jump over a broomstick. Enslaved people were not permitted to be legally married before the Civil War. Ceremonies and marriages were symbolic rather than legally binding.

Before being emancipated, Lewis was required to get permission and a pass from his enslaver to visit Adaline and their children during the week. When freedom was announced, Lewis immediately made his way over to the Turner plantation to retrieve Adaline and their children. However, this was more complicated than Lewis hoped. Adaline did not know the people who enslaved Lewis or how they would treat her. Because of this, they continued to live on separate plantations for a few years until Adaline joined him. They eventually returned to the Turner plantation together where she worked for them until she retired.

Bryant Huff

Bryant Huff was born in Warren County and enslaved by Mr. Rigerson. Like many other enslaved people, Bryant’s family was separated before the war. His sister was enslaved by a judge on a neighboring plantation while his brother and father were sold from the Rigerson plantation after rebelling multiple times against mistreatment. The Civil War and emancipation allowed for the family to be reunited. His sister left the plantation she had lived on and joined the family. His father was able to flee and return to the Rigerson plantation a few months before the war ended. However, his brother passed away before he was able to reunite with his other family members.

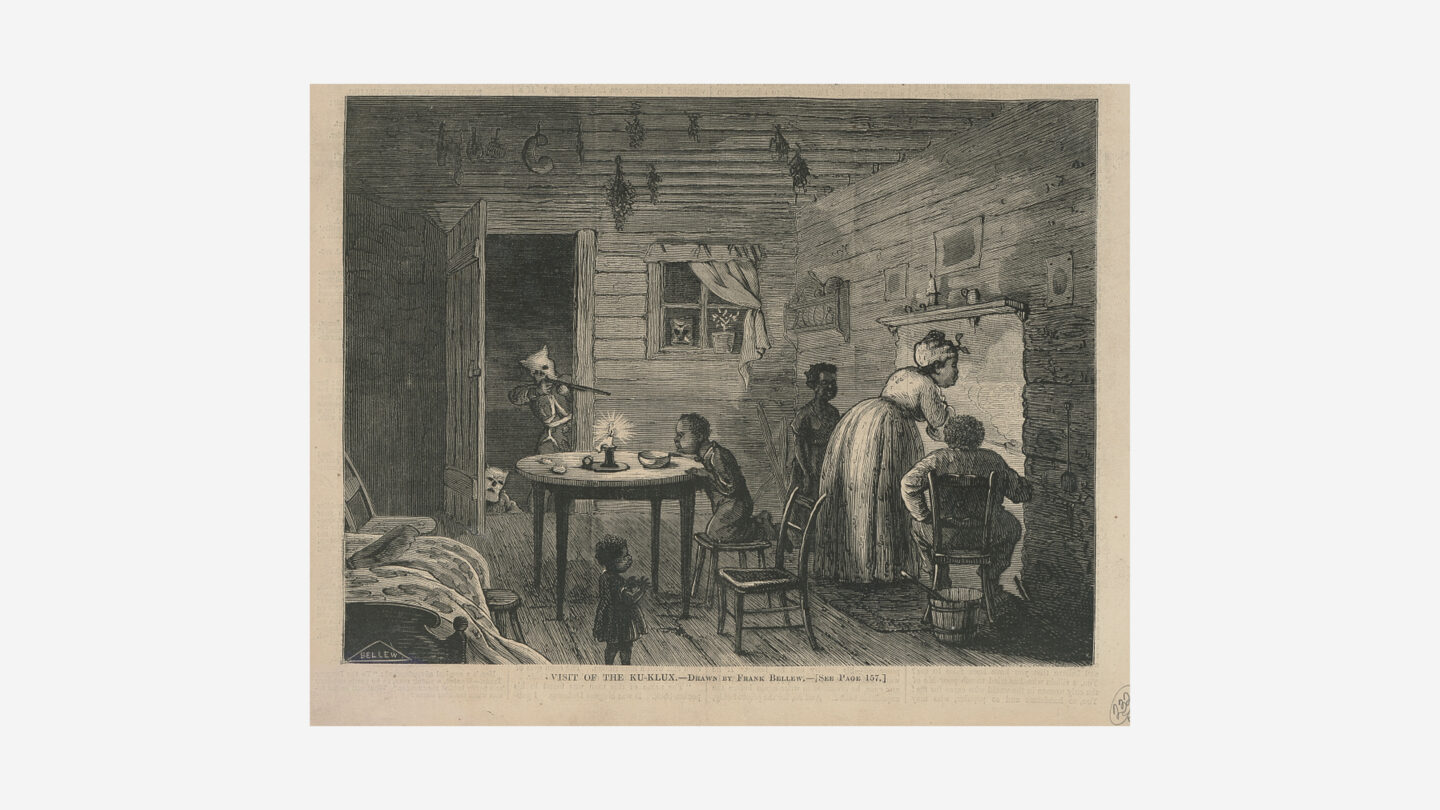

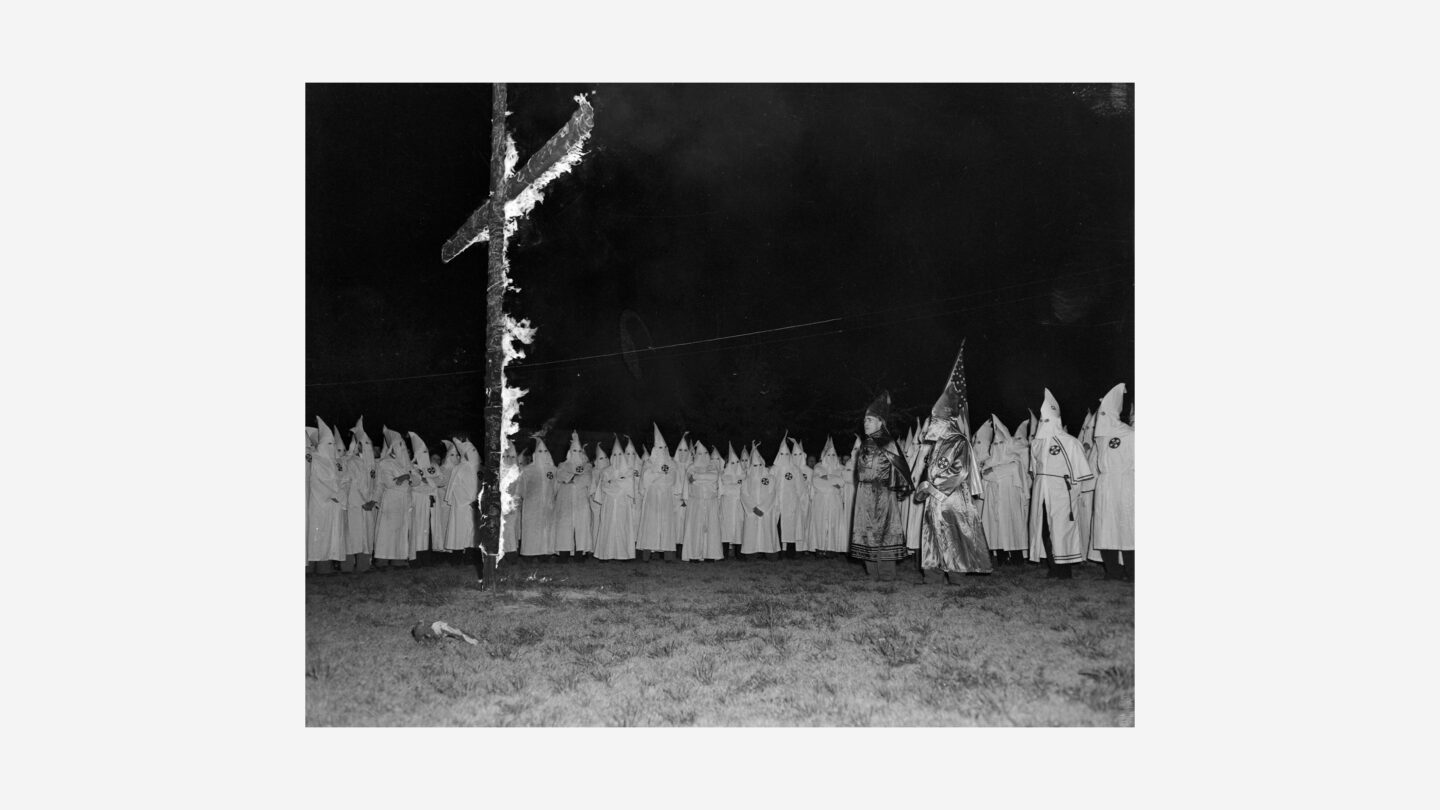

The family then moved off the plantation hoping for better treatment than what they had experienced during slavery, but Bryant described this as a “leap from the frying pan into the fryer.” The formation of the Ku Klux Klan complicated freedom as they worked to control the liberties of freedmen. The Huff family was attacked and threatened in their home by the KKK on suspicion of being part of an organized Anti-KKK group. The plantation owner of their new home had organized the attack, and the Huff family was forced to flee back to the Rigerson plantation. Bryant eventually left his family in pursuit of an education. He went on to teach at the same school he had attended.