Georgia in 1922 | After the Vote

As Georgia women began to elect their government and determine the laws that governed them, much of their post-1920 political activism continued in ways that were established before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. In the early 1920s, Georgia was fairly split between the sexes, with the female population taking a slight majority. Despite population gains, women were not represented in the legislature until 1922.

Opposition to the participation of women, Blacks, and non-elites in government did not dissipate after suffrage. In her book, The Weight of Their Votes: Southern Women and Political Leverage in the 1920s, Historian Lorraine Gates Schuyler validates this shortcoming:

In the South, debates over woman suffrage had been marked not only by apocalyptic predictions about the emasculation of white men and the demise of the white southern family but also by shrill cries of “the black peril” and states’ rights. For many white southerners, Reconstruction, Populism, and the days of vigorous Republican competition in the South were not distant memories but vivid historical lessons that seemed destined to recur should white southern Democrats weaken in their resolve. Electing women did not stop that.

The region’s elitist political ceiling made things more difficult for women hoping to be elected. At the time, according to Schuyler, “politics [was] viewed as the concern of a small, powerful elite who ‘inherited’ the right to govern by social and family ties. Individual citizens were not nor were they expected to be active in politics.” Indeed, while Georgia’s first women legislators worked hard before and after winning their legislative seats, they all benefited from the privilege of their racial and social status.

The First Georgia Women Elected and Appointed to Legislatures

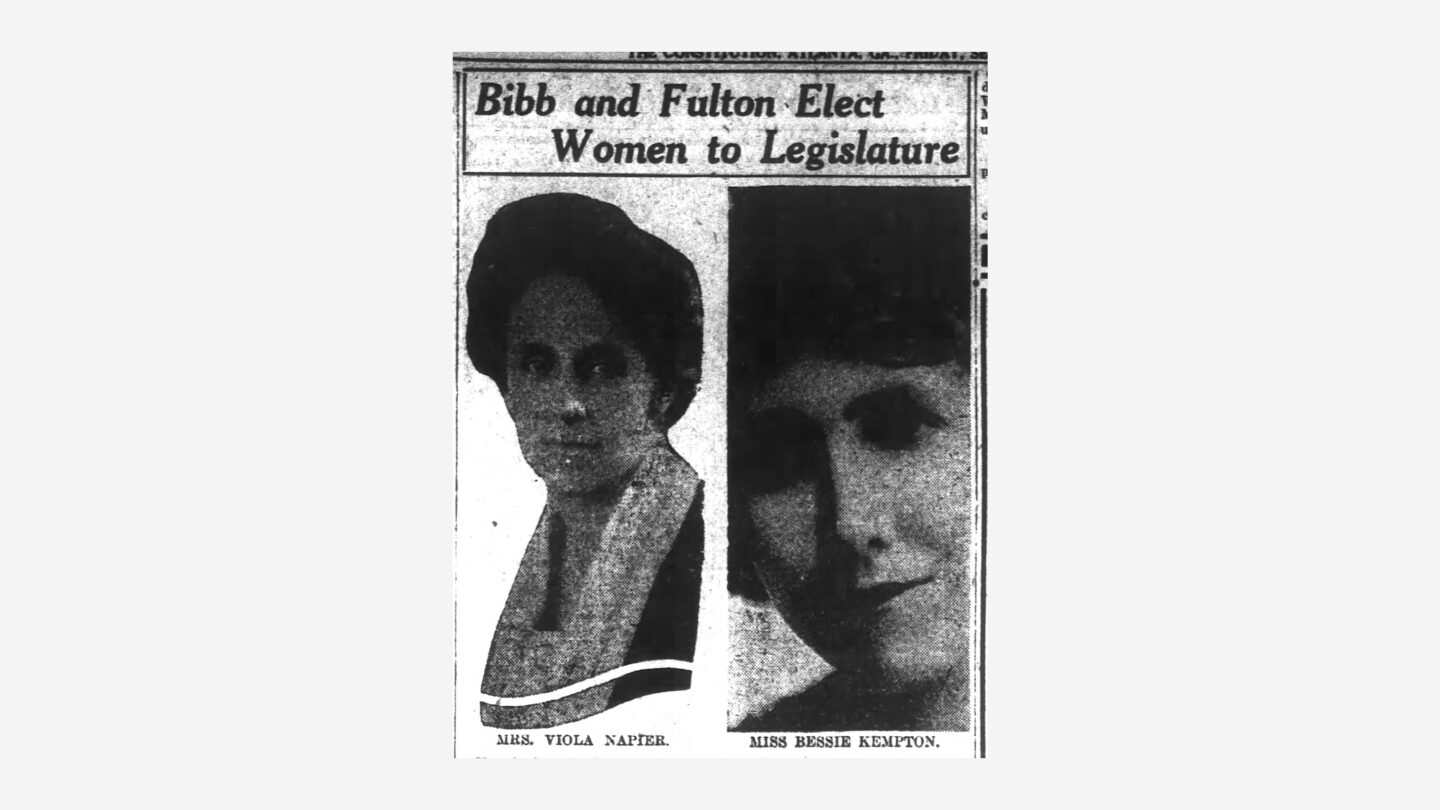

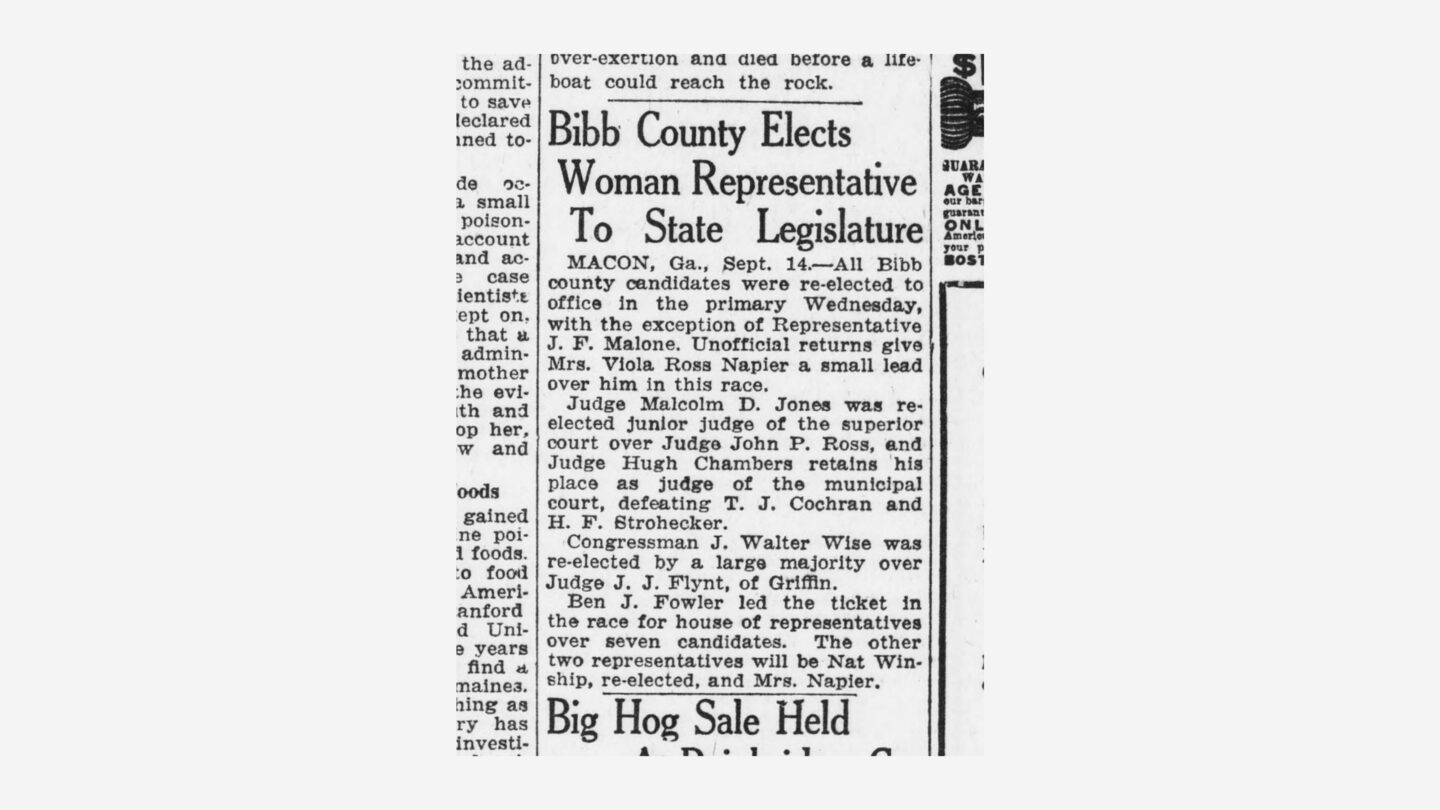

On September 13, 1922, Viola Ross Napier and Bessie Kempton Crowell became the first women elected to the Georgia House of Representatives. While they share this place in history, their paths to the legislature and careers after the legislature were very different.

“Going Underground to Understand Atlanta History,” V12 Productions/YouTube.

Bessie Kempton Crowell (1893–1981) in the Georgia House of Representatives (Fulton County) September 13, 1922–1931

Before running for and winning a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives, Bessie Kempton Crowell, then Bessie Kempton, was an Atlanta Constitution reporter and a well-connected young leader in Atlanta society. In 1914, she was the president of the Pan-Hellenic Council of Atlanta, which included the federated forces of 18 college sororities in the city. She graduated from Shorter College and was a member of Alpha Kappa Psi.

At the Atlanta Constitution, she covered a broad range of issues. Her wide-ranging investigations included reporting about highway construction and better methods for strengthening highway bridges for heavy motor traffic, disenfranchisement, and women in the business world. Because of her reputation as a community leader and respected journalist, supporters urged Kempton Crowell to run for the Georgia General Assembly as early as October 1921.

Ultimately declaring her candidacy in June 1922, she broke from traditional campaign protocol, announcing in an article in the Atlanta Constitution that she was “running without any platform promises.” In the write-up she emphasized that “candidates have always been willing to accept any vote-catching doctrines that time decays” and that she was “not going to fall into [that] error.” Of course, according to the article, Kempton Crowell had “definite ideas about new and remedial legislation needed by Fulton county and the state of Georgia,” but she did not want to make any claims or promises until she did her research. She strongly voiced her concerns, saying, “It would be pure folly for me to state what my present attitude is” without the benefit of time and due diligence. The Atlanta Constitution also captured Kempton Crowell campaigning in August 1922 and noted that she had “wonderful qualities as a public speaker and always holds her audience in close attention.” At the time, she was one of 12 candidates—and the only woman—running for the Fulton seat in the statehouse. But she rejected any gendered rhetoric and stated, “I am … not running as a woman, but because I believe I can be of good service to the people of Fulton county.”

After taking her seat in the Georgia House of Representatives in September 1922, Kempton Crowell deployed her diligence strategy to become an esteemed and effective legislator. In 1923, she introduced a bill that created a new division in the Fulton superior court. In 1925, she was noted in the City Builder as a member of the small group of representatives deserving special praise for “taking the initiative and steer[ing] the [Viaduct Bill] to speedy success.” One Atlanta resident at the time considered the passage of the Viaduct Bill “a clarion call to Atlanta to rally now for the most remarkable era of growth we have ever known.” Kempton also apparently had a well-received sense of humor that she took with her to work. As a joke, she co-sponsored and introduced a proposed bill to tax red neckties, variegated socks, colored shirts, and stockings with runs in them. Some took the measure seriously and wrote to the Atlanta Journal in dismay. She seemed to both enjoy and respect her time as a legislator.

Kempton Crowell’s legislative legacy remains visible even today. The “Viaduct Bill” she helped pass authorized the construction of the viaducts that lifted downtown storefronts above the railroad tracks and created what came to be known as Underground Atlanta. The area is currently undergoing a phased redevelopment that some claim will “redefine” downtown Atlanta. In 1931, her legislative career ended, and Kempton Crowell went on to become the editor and publisher of the Fulton County Daily Report, which her father founded in 1890. She died in 1981.

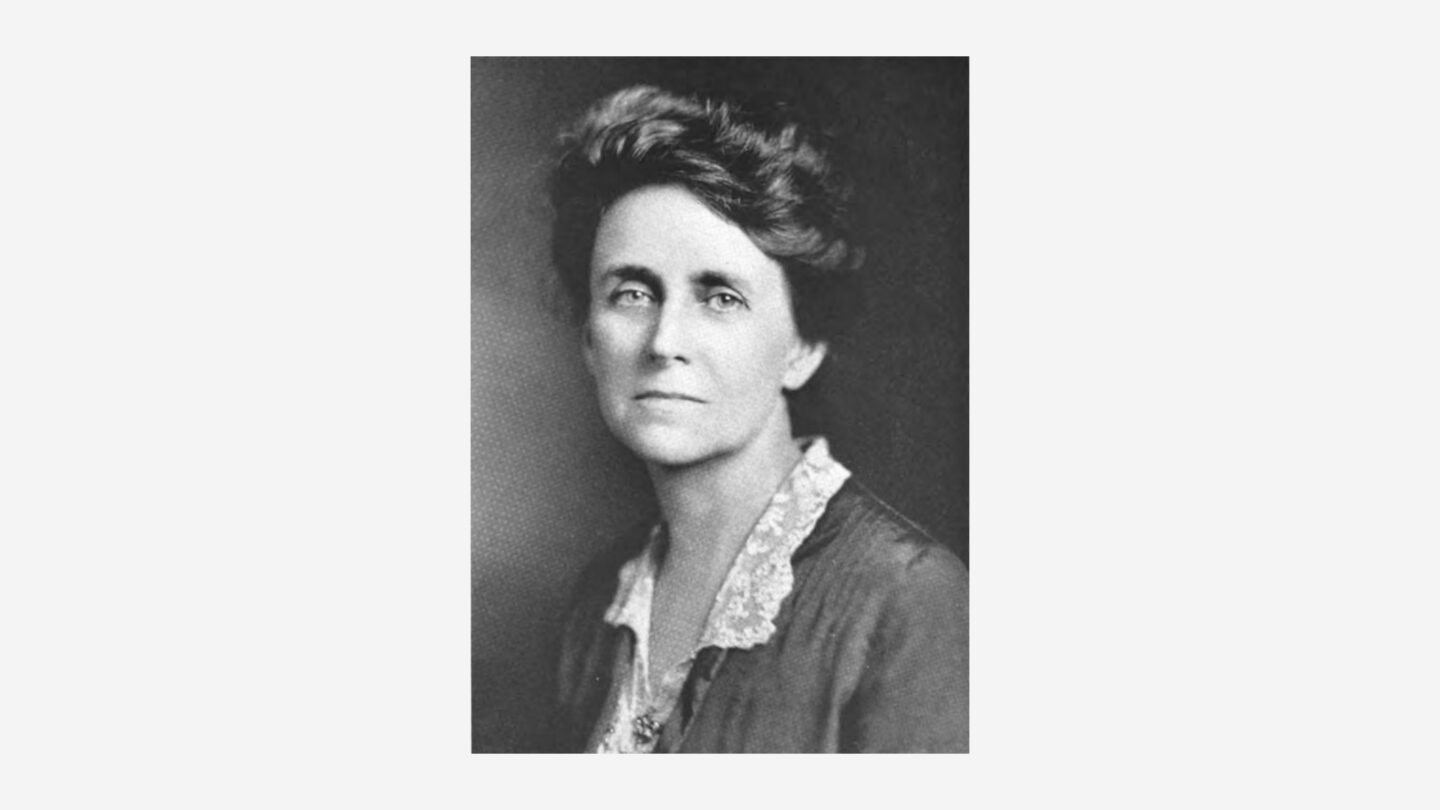

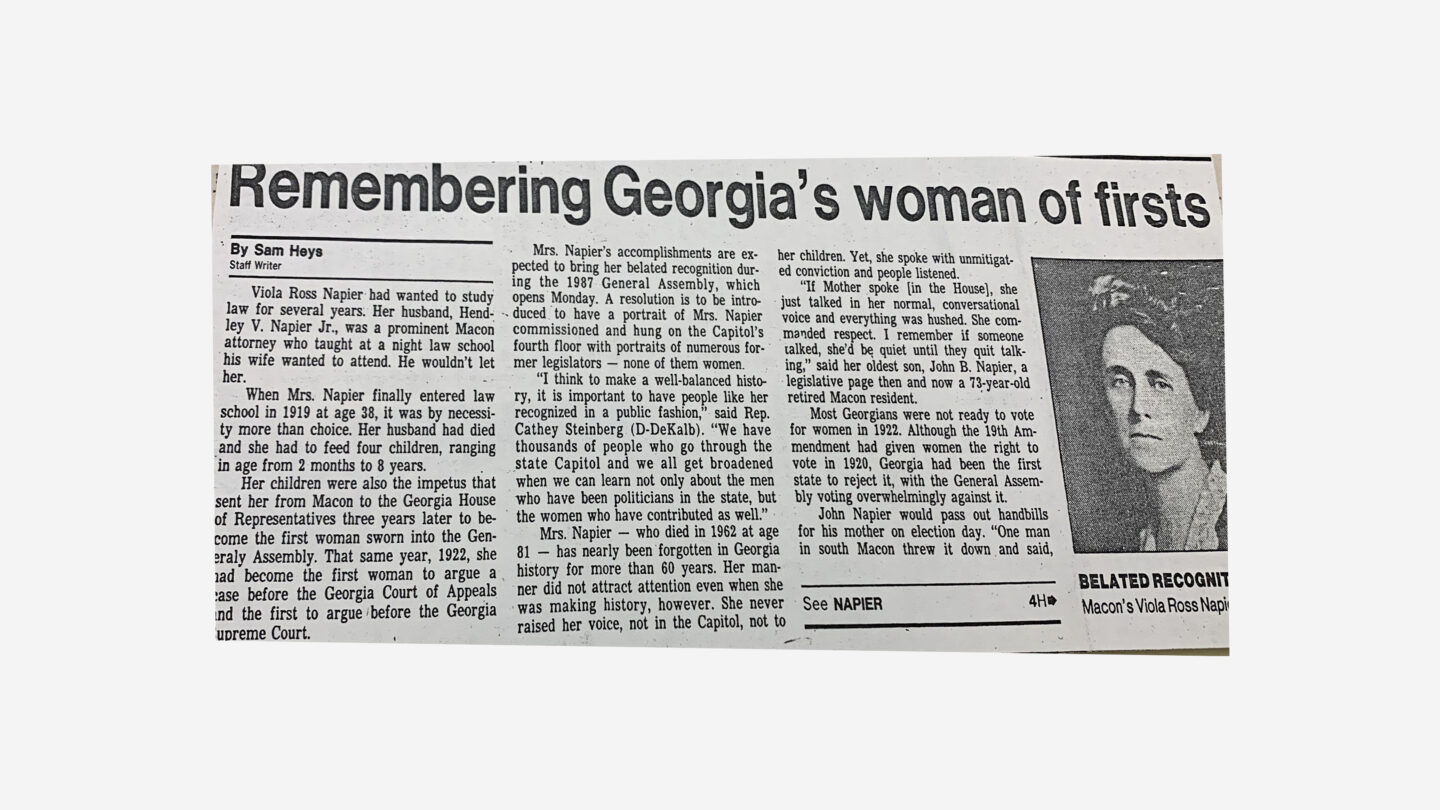

Viola Ross Napier (1881–1962), Georgia House of Representatives (Bibb County) September 13, 1922–1926

Viola Ross Napier earned a resume of historic firsts. In addition to her shared designation as the first woman legislator in the Georgia General Assembly, she was the first female lawyer to argue in front of the Georgia Court of Appeals and the Georgia Supreme Court, as well as the first woman to win a pardon for a convicted client before the client served any of her sentence.

Before becoming an attorney, Napier was a schoolteacher until her attorney husband died in the 1918 flu epidemic. She attended Judge E. W. Maynard’s night school and passed the bar exam in 1920. After Macon law firms refused to hire her, she started her own practice and blazed an impressive trail of firsts from the courtroom to the State House of Representatives.

During Napier’s time in the legislature, she often focused on education, children’s rights, and protection for citizens with special needs. In 1923, she worked with Kempton Crowell and the American Bar Association to introduce a bill compelling the teaching of the principles of the State and United States Constitutions in public schools. In 1925, she worked with the Children’s Code Commission and introduced a bill comprising eight laws affecting “dependent, delinquent, neglected, and defective” children. As chairman of the state legislative committee for the DeKalb County League of Women Voters, she presided over an all-day citizenship school on legislation in June 1927 and remained active in various voting groups.

After she lost her election in 1927, she became the city clerk of the court in Macon. However, her duties in that role far exceeded the scope of a typical court clerk. In service to Macon and at least five Macon mayors, she provided unofficial legal counsel, maintained minutes of city council meetings, managed the sales and inspection of city business licenses, managed the city pound, and wrote mayoral speeches. After a distinguished career, she retired as Macon city clerk at 72 and died in 1962.

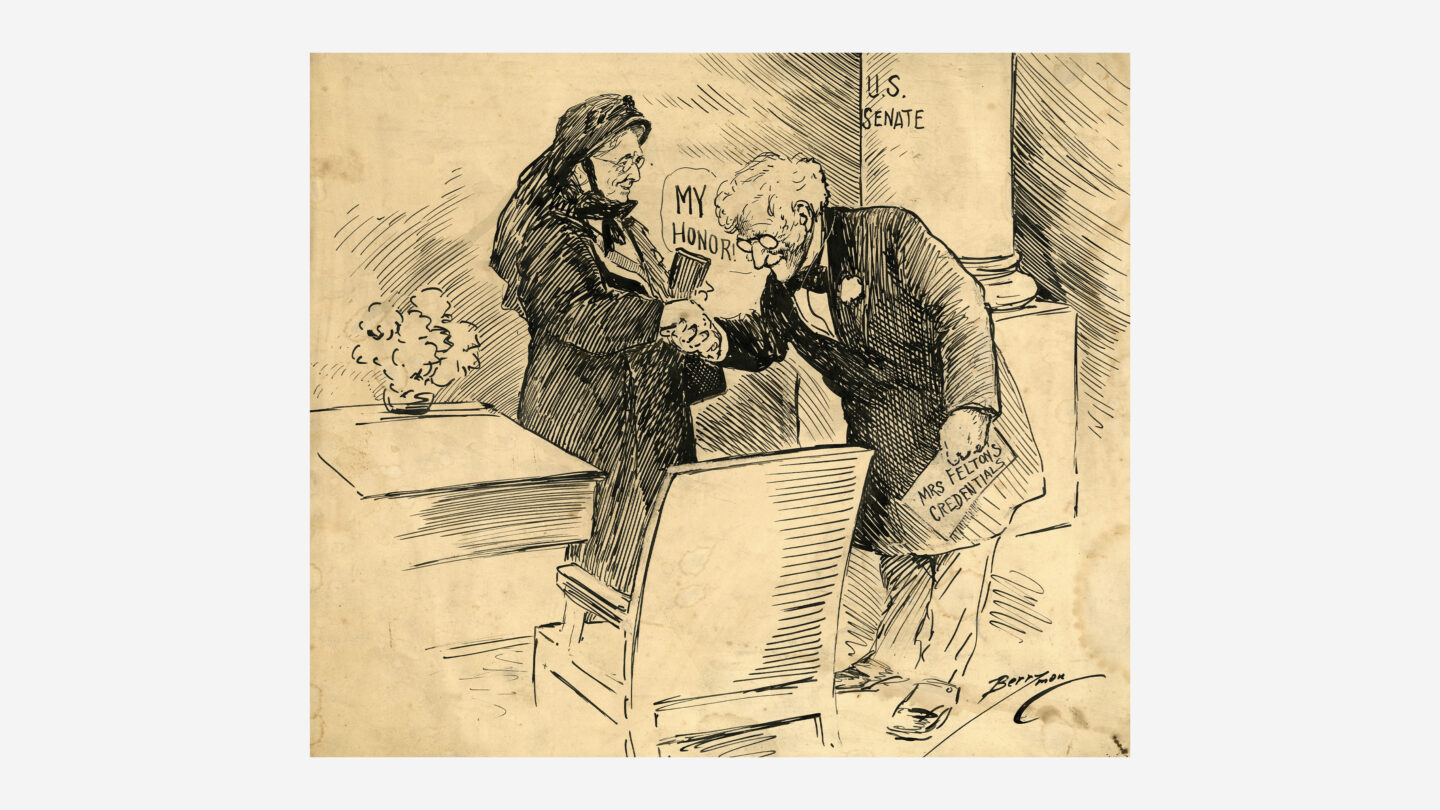

Rebecca Latimer Felton (1835–1930), U.S. Senate term November 21, 1922–November 22, 1922)

On November 21, 1922, Georgia native Rebecca Latimer Felton became the first woman to serve in the United States Senate when she was appointed for a term of one day. She was appointed to replace U.S. Senator Thomas Watson, who had just died. Although Walter F. George had run for and won the special election to replace Senator Watson, Georgia’s women suffragists campaigned to get Felton the short appointment and convinced Walter F. George to wait and allow Felton to be sworn in.

Felton captures the essence of how white women of a particular social status must have felt after winning the vote and elected office, writing in her book, The Romantic Story of Georgia’s Women:

Many and extraordinary have been the changes throughout Georgia and throughout the world in these years. Yet it is doubtful whether there has been anything more remarkable than the changes that have affected women. Their place in community life, their work, their customs, their whole point of view, have been turned upside down within my memory. They have emerged from a subdued background to a place in the sun.

Felton was a veteran political operative. Before her Senate appointment, she managed her husband’s political campaigns and served as his press secretary. When Dr. William Harrell Felton was elected to his second U.S. Senate term in 1876, a newspaper headline read, “Mrs. Felton and Her Husband Returned.”

Felton was a woman of dynamic dichotomies. Of her political and social views, biographer John E. Talmadge diplomatically noted, “[h]er prejudices and loyalties were not readily changed by foreign ways or new experiences.” She was a white supremacist and spoke vigorously in favor of lynching. Felton, Congress’s last former slave owner, also spoke out against the convict leasing system. While seeking suffrage for women, she decried voting rights for Black people.

Felton was a voracious writer before and after her one-day Senate term. She wrote a column for the Atlanta Journal for nearly 20 years. She authored three books: Country Life in Georgia in the Days of My Youth (1899), My Memoirs of Georgia Politics (1911), and The Romantic Story of Georgia’s Women (1930). Felton died in 1930.

With the elections and appointments of Bessie Kempton Crowell, Viola Ross Napier, and Rebecca Latimer Felton, Georgia women made the first step toward political parity.

In the next part of our “100 Years of Georgia Women Legislators,” we will focus on women elected or appointed to the General Assembly from 1925–1950.

For Further Reading

Today in Georgia History: September 13 – Viola Ross Napier and Bessie Kempton Crowell

Today in Georgia History: November 21 – Rebecca Latimer Felton