Editor’s note: Starting with the “firsts” in 1922 and ending with possible new “firsts” in 2022, this article (and subsequent articles in this series) celebrates women and reflects on the journey Georgia women have had to take to be elected and appointed to legislatures in the state.

“Social advance depends as much upon the process through which it is secured as upon the result itself”

“I may be the first woman member of Congress,” Montana Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin said, “but I won’t be the last.” A century of women legislators has proven her right. On August 29, 1916, Rankin became the first woman in the nation elected to Congress and entered the U.S. House of Representatives four years before most women in the United States even had the right to vote.

It has been 100 years since the first woman was elected to the Georgia legislature and 100 years since the first woman, a Georgian, was elected to the United States Senate. Bessie Kempton Crowell and Viola Ross Napier were both elected to the Georgia House of Representatives on September 13, 1922, and Rebecca Latimer Felton was appointed to the United States Senate on November 21, 1922. However, the question remains: To what degree did these gender milestones impact women’s political power?

The historical perception for a long time after women secured the right to vote in 1920, was that women made little use of it, became inactive, and were ineffective in politics until the 1960s feminist wave. Many historians now challenge this argument. Through their work in suffrage, enfranchisement, and as legislators, Georgia women have proven the opposite: That over the course of a century, Georgia women have continued to fight to expand and protect voting rights, have remained politically active despite the odds, have increasingly sought public office, and have led the implementation of significant legislation.

Before Georgia Women Could Win Elections, They First Had to Win Suffrage

The path to gender political parity was a circuitous one. Women’s suffrage and enfranchisement and women in elected and appointed political office are inextricably connected on the path to gender political parity. Therefore, a refresher on suffrage and enfranchisement is instructive and shows that women, especially women of color, had to continue to fight for voting rights and political position after the 19th Amendment and after the first women were elected and appointed to legislatures.

Before the 19th Amendment: Suffrage and Anti-Suffrage

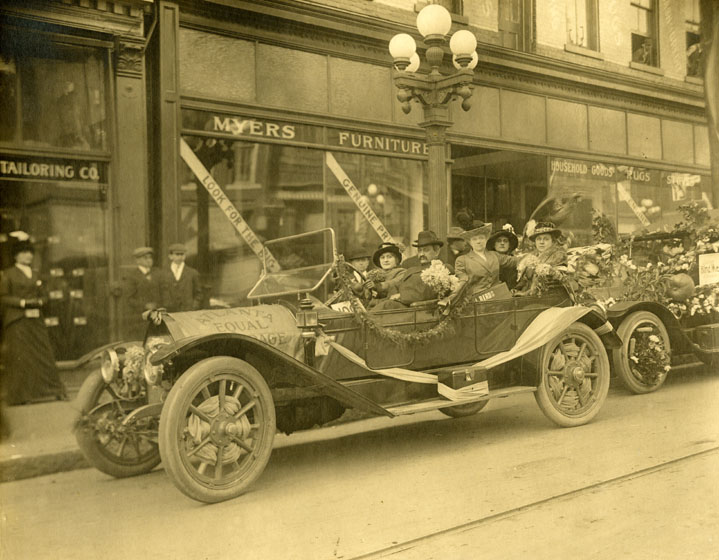

The journey began when women first organized and collectively fought for suffrage at the national level in July 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention and in the late 1800s regionally. Because of the suffrage movement’s ties to abolitionism, Southern women’s suffrage groups were slower to organize as compared to groups in other regions. The three leading state associations working for the enfranchisement of white Georgia women were Georgia Women Suffrage Association (created in 1890), Georgia Woman Suffrage League (created in 1913), and the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia (created in 1914). All three were affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and often joined forces to offer citizenship and parliamentary procedure classes to women, circulate petitions, stage rallies, or lobby for women’s suffrage legislation.

In Georgia, like most Southern states, suffrage efforts were largely segregated. African American Georgia women such as Janie Porter Barrett, Mary McCurdy, and Adella Hunt Logan were largely kept out of Georgia state-wide suffrage efforts but were instrumental in advancing women’s suffrage on a national scale. Another gender parity facilitator, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW), founded in 1896, was an umbrella group for women’s organizations at the state and local levels. It operated through a series of departments and served as an instrument to unite African American women and to educate them in the science and techniques of reform. Black women’s advocacy for women’s suffrage was also closely tied to the parallel campaign for the re-enfranchisement of Black men.

The path of suffrage meandered locally and nationally from the mid-19th century, and for 42 years, some version of the 19th Amendment or similar suffrage legislation was introduced at every session of Congress but was either ignored or voted down. While many may have some understanding of local, regional or national suffrage movements, most do not have a working knowledge of anti-suffragists, who placed roadblocks to women’s voting rights. Georgia anti-suffragists successfully lobbied the Georgia House of Representatives to reject suffrage amendments for more than seven years and were a primary reason that Georgia became the first state to vote against the ratification of the 19th Amendment. White anti-suffragist Georgians contended that voting women challenged the Southern sacraments of patriarchy, white supremacy, planter-industrialist politics, and women’s moral superiority. Major anti-suffrage organizations that lobbied against the vote for women in Georgia included the Georgia Chapter of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, whose leadership included Mildred Lewis Rutherford of the Lucy Cobb Institute in Athens and the Georgia president of the UDC.

Inside page from The Cedartown Standard featuring an article about women getting the right to vote. The Cedartown Standard, Cedartown, Georgia, November 11, 1920

Despite substantial setbacks, the 19th Amendment finally passed Congress in 1919. In May, the House of Representatives passed it by a vote of 304 to 90; two weeks later, the Senate approved it 56 to 25. After it passed the U.S. House and Senate, the amendment went to the states for ratification. Ultimately, the legal right of women to vote, women’s suffrage, was established nationally in the United States with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in August 1920. Even though the future still held decades of struggle to include African Americans and other minority women in the promise of voting rights, the face of the American electorate was forever changed.

Georgia women were not able to vote nationally until 1922

While women across the United States were able to vote in the 1920 presidential election, Georgia women were not able to cast their ballots in the 1920 national election because of a rule requiring voters to register six months before an election. Unlike many other states, the state of Georgia refused to waive this registration rule and made all, but one Georgia woman wait until 1922 to take part in a national election. Only Mary Jarett White of Stephens County, a devoted suffragist, registered in time for the 1920 national election. She appeared at the registrar on April 1, 1920, to register and pay her poll tax. On Election Day, White cast her ballot; in doing so, she became “the first and only woman in Georgia who would legally vote in the November presidential election.” Georgia did not ratify the 19th Amendment until February 20, 1970, nearly 50 years later.

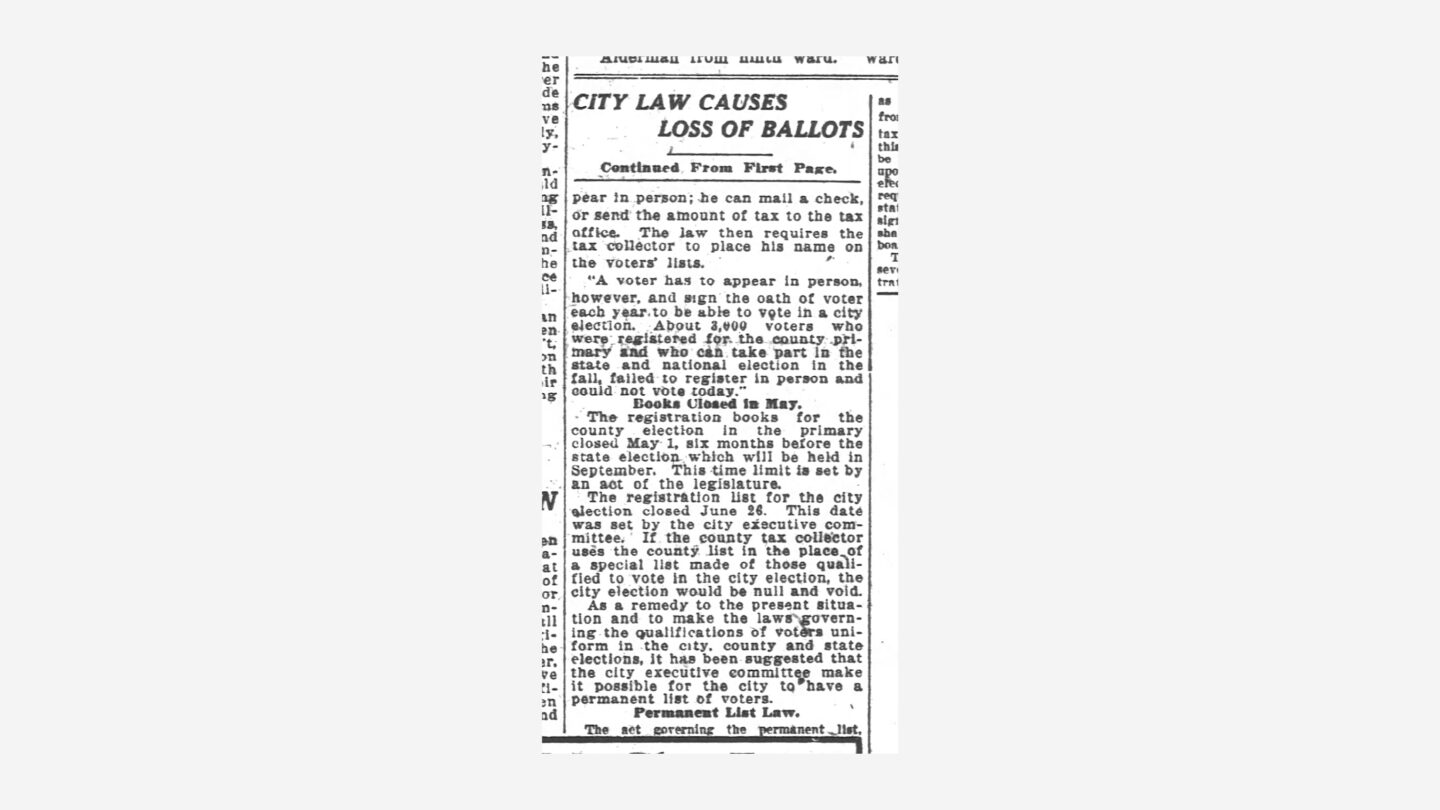

Complete Enfranchisement for Women

Without a centralized or federal enfranchisement organizational structure in place, the voter registration process for women played out differently depending on an individual’s race, ethnicity and geographic location. Accordingly, complete women enfranchisement was not immediate and would not be realized by some women until 1975. Some Georgia voting rules, such as the Voting Act of 1913, disenfranchised not only women and people of color, but also some white men. One of our first women legislators, Bessie Kempton Crowell, wrote about the Act of 1913 in a July 29, 1920, newspaper article.

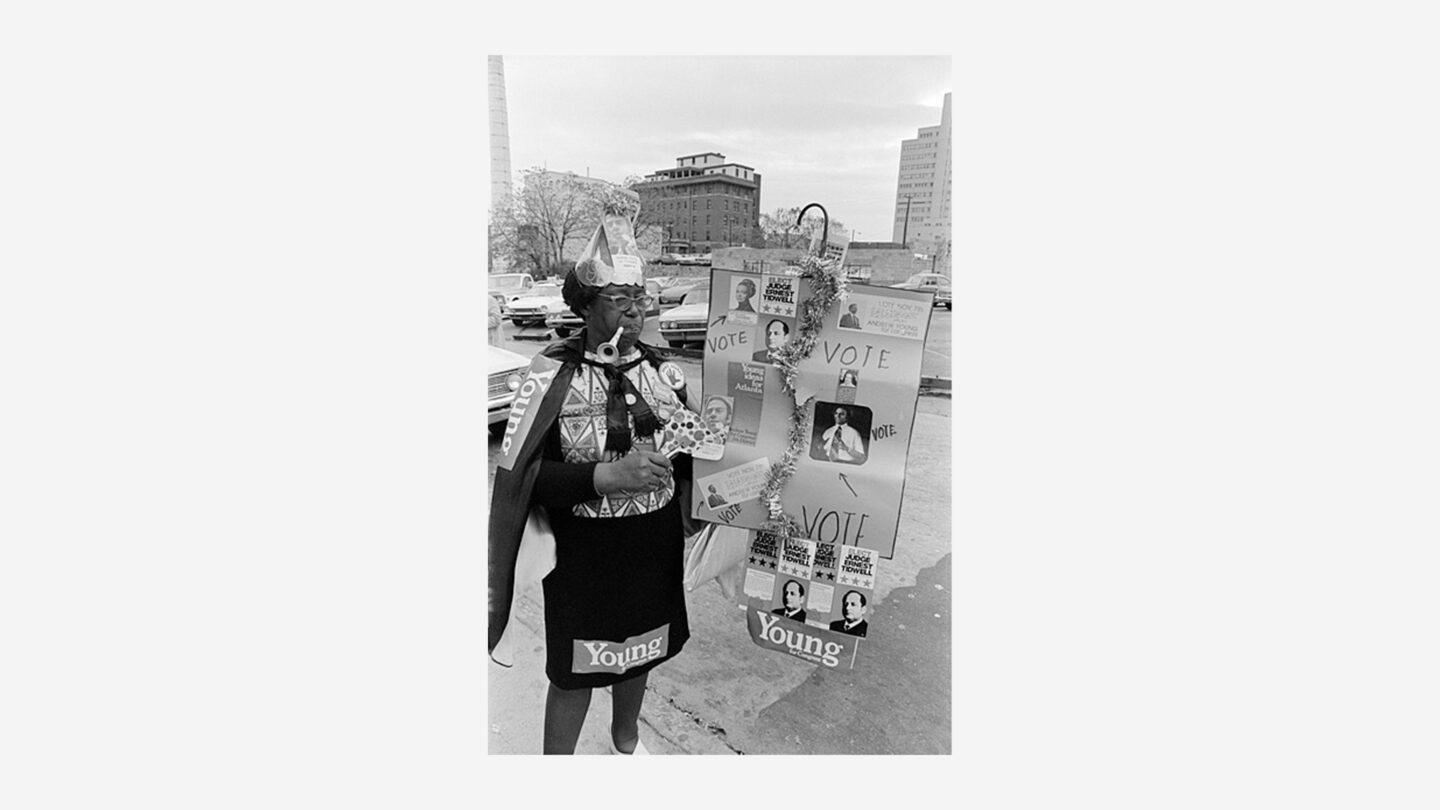

The path was more arduous for some; and it would be several decades before all women, particularly women of color or women speaking a foreign language, were able to exercise their voting rights. While the 19th Amendment made it legal for Black women to vote, other impediments—including white only primaries, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, poll taxes and racial terrorism—prevented many black women and men from casting their ballots. The 1924 Snyder Act granted Native Americans citizenship rights, including the right to vote. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 sought to overcome legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented racial minorities from exercising their right to vote as guaranteed under the 15th and 19th Amendments to the Constitution. The 1975 extension of the Voting Rights Act ended discrimination against “language minorities,” including those who speak Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Spanish languages, by requiring certain jurisdictions to provide translation materials for voter registration information and ballots.

The Legacy of Suffrage: Voting and Women Legislators

The battle for the right to vote mobilized and supplemented other women’s issues. Many of the same women who fought for suffrage argued for the right for safe working conditions, the right to operate and transact businesses without the involvement of familial men, the right to own property, and the right to have more control over their bodies, including the right to birth control. Legislative reform, better legislation for women, and our first women legislators are a part of the legacy of women’s suffrage. The movement provided information and a mobilization apparatus for women and men politicians to draw on after the vote was extended to white women. Together, both post-suffrage activism and electoral incentives were essential for reform and provide an instructive reminder for feminist mobilization today.

Re-examining suffrage and the history of women’s participation as elected officials in Georgia is both timely and relevant as we are experiencing a resurgence of certain elements of Southern patriarchy locally and nationwide. Laws related to women’s rights and their bodies are being enacted and retracted by majority male leadership. Voters’ rights are at risk, and new disenfranchisement laws are springing up locally and nationwide. Alas, even after 100 years of Georgia women in the legislature, not enough women have a seat at the legislative tables.

As we commemorate and celebrate this centennial milestone, we must also reckon with the reality that the legacy of women legislators suffers from the same dichotomy that women’s suffrage endured: equality and exclusion. While many professed a desire for equal voting rights and the resulting and complementary right to run for elected office for some, these same “equality” advocates actively and successfully excluded women of color from voting and from elected positions in Georgia for decades after white women were voting and being appointed and elected to legislatures. It reminds us that the gains that women have won have rarely ever been equally experienced.

Certainly, the path to gender parity is becoming easier to traverse and more well-traveled. The 2022 Georgia political campaign season has already made history. Ten state executive offices are up for election in 2022, from governor to two public service commissioners; and for the first time ever, a woman is running for every available seat. In some cases, more than one woman is running for the office. After the November 2022 elections, we will see if elected officials in Georgia finally become a better reflection of the actual population of women citizens and voters, but according to the Center for American Women in Politics, the following firsts are a possibility in Georgia for 2022:

- Former State Representative Stacey Abrams (D) was unopposed in the Democratic primary for governor of Georgia. She will challenge incumbent Governor Brian Kemp (R) in November, marking a rematch of the 2018 gubernatorial election where Abrams lost to Kemp by 1.4 points. Abrams became the first Black woman to be a nominee for governor of any state in 2018; if successful this year, she will be the first Black woman governor in the U.S. as well as the first woman governor of Georgia. She would also be the first Black woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.

- State Representative Bee Nguyen (D) won the Democratic nomination to challenge incumbent Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger (R). If successful in November, Nguyen will be the first Asian American woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.

- Janice Laws Robinson (D) won the Democratic nomination to challenge incumbent Insurance Commissioner John King (R). If successful in November, she will be the first Black woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.

- Alisha Thomas Searcy (D) won the Democratic nomination to challenge incumbent Superintendent of Public Instruction Richard Woods (R) in November. If successful, she will be the first Black woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.

- Shelia Edwards (D) won the Democratic nomination to challenge incumbent Public Service Commissioner Fitz Johnson (R, District 3) in November. If successful, she will be the first Black woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.

- Nakita Hemingway (D) won the Democratic nomination for commissioner of agriculture. If successful, she will be the first Black woman elected to statewide executive office in Georgia.