Atlanta’s Paralympic Games represent many significant benchmarks for Paralympic and disability history. By the 1990s, an event that originated as a veterans assistance program had grown into a high-profile international sports competition. In the U.S., a decades-long backdrop of advocacy, activism, and legislation helped boost the scope of the event and gain momentum for bringing disabled athletes into the Olympic spotlight. Looking back at how these Paralympic Games came to be, across the globe and in Atlanta, a larger picture aligns with the arc of progress and public discourse for the disability rights movement.

Paralympic Games organizers, city leaders, and representatives of the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change gathered in August 1996 to kick off what was then the largest Paralympic torch relay to date and the first on U.S. soil. Just one day after the ceremonial close of the Olympic Games in Atlanta, this event marked the beginning of the summer’s Paralympic chapter.

Capitalizing on the symbolic message and local significance, the Paralympic flame was lit from the fire of the Eternal Flame that marks Martin Luther King Jr.’s tomb. This highlighted the close tie between the Civil Rights Movement and disability rights platform of the Paralympic Games. The flame was then flown to Washington, D.C., where the first torch of the relay was lit in a ceremonial event at the White House.

Over the next 10 days, supporters of the Games, disabled and able-bodied individuals, government representatives, Paralympians, and local celebrities participated in the relay. Runners, walkers, horseback riders, water skiers, wheelchair users, bicyclists, and even lawn mower drivers took part in the 1,000-mile route from D.C. to Atlanta. On August 16, 1996, Paralympians brought the flame into Centennial Olympic Stadium to light the Olympic Cauldron for the second time that summer and launch the Games.

Paralympic Torch Ceremony | C-SPAN, Washington, D.C., August 6, 1996 | Courtesy C-SPAN

Growth and Momentum at Home and Abroad

The Paralympic Games are younger than their Olympic counterpart. The 1960 Games in Rome are recognized as the first official Paralympic Games, but this was a retroactive designation, since the word “Paralympic” was not widely used until the 1980s. The 1960 event was an expansion of efforts begun by Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, a Jewish, German-born doctor, at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. Dr. Guttmann organized a one-day competition for British World War II veterans with spinal cord injuries. Timed to align with the 1948 Olympic Games in London, the competition was called the International Wheelchair Games.

The event, later called the Stoke Mandeville Games, became more common over the years and slowly integrated participants from other nations. The ninth iteration was hosted in Rome. By then, participation was no longer restricted to injured veterans, but it was still limited to those with spinal cord injuries. The event in Rome brought together 400 athletes from 23 countries to compete in eight sports.

Italian Paralympians | First official Paralympic Games, retroactively designated, Unidentified photographer, Rome, Italy, September 16, 1960. Courtesy Keystone / Stringer, Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Over the next few decades, the new Games grew and worked to establish their link with the Olympic Games—a goal that would ideally result in a unified, inclusive, and accessible showcase of international sportsmanship. From Rome forward, the Paralympic Games continued to take place in the same year as the Olympic Games. By 1976, winter games joined the regular Paralympic cycle. In that same year, the summer Paralympic Games in Toronto saw an increase in athletes with inclusion of individuals with disabilities beyond spinal cord injuries.

These were the early years of the Paralympic practice of classifying disabilities. Classifications enabled Paralympic organizers to include a broader section of the disability community in the Games, while balancing competition and ability. Early Paralympic competition classifications included vision impairment, amputation, cerebral palsy, and paraplegia.

Clip from A Triumph of Human Spirit commemorative video International Paralympic Committee and United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee, September 1996. Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The 1988 Games in Seoul marked the start of a greater link between the Paralympic and Olympic Games, when they were hosted in the same city, using the same facilities. One year later, sports officials and Paralympic advocates founded the International Paralympic Committee as the governing body for the international event. This agency provided central organization and advocacy, pushing for continued awareness of disability sports and equal rights for the disabled community.

In the U.S., the growth in scope and visibility of the Paralympic Games was largely in step with the progressive trajectory of disability rights. Prominent stories of wounded veterans coming home from World Wars I and II brought pressure on the government regarding its role in disability assistance and rehabilitation. Prior to this era, disabled individuals were mostly institutionalized or pushed to fit into a world without equal accommodations. In many cases, they were abused, marginalized, and denied their basic rights, with some undergoing forced sterilization.

The Civil Rights Movement presented more opportunities for disability rights advocates and disabled individuals to make their causes and experiences known. Issues of employment equity and equal access to public spaces and transportation aligned with struggles of race-based injustices. Disabled people across the U.S. began to organize locally and then nationally. They sought rights, institutional change, and legislation that would support independent living and self-determination of medical treatment.

These actions moved the discourse to ways to empower or support disabled individuals rather than fix or cure disability.

The pressure resulted in an initial win on the federal stage with the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Modeled on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, this legislation took a first stand at removing societal barriers for disabled individuals and barring discrimination. Activism and advocacy ramped up over the next decade. In the mid-1980s, groups called ADAPT, or Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, began popping up in cities across the U.S.

Atlanta’s chapter formed in 1986 and their work brought pressure on the MARTA transit system to install accessible lifts across its bus fleet. Continued activism, court decisions, and healthcare initiatives in Georgia coalesced a community of engaged disability rights advocates, activists, and allies.

In Atlanta, the Shepherd Spinal Center opened in 1975, filling a gap for a healthcare center that focused on spinal cord injury care and rehabilitation in the Southeast. Alana and Harold Shepherd and their son James, whose injury prompted the founding, quickly found themselves at the center of disability awareness discussions in Atlanta. The center operated a prominent disability sports arm for rehabilitation and became involved in accessibility issues and disability events across the city. It assisted in launching a wheelchair division of Peachtree Road Race by the late 1970s.

Wheelchair Competitor Crosses the Finish Line at Peachtree Road Race, Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, July 4, 1979, Courtesy Atlanta Track Club

In July 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) into law. The act made civil rights protections of people with disabilities far more comprehensive than its 1973 predecessor. It also solidified a cultural shift in the country’s perception of the disabled community. The act secured equal accommodations for the disabled in employment, public spaces, public services, transportations, and telecommunications. It launched changes to our built environment that ensured new public schools, venues, and buildings were truly accessible to all the public.

The years surrounding the signing of ADA into law were the backdrop for Atlanta’s path to Paralympic host city. This context highlights how disability sports are often a tool to help expand recognition for the disabled community and leverage continued social change.

It’s Atlanta Again

In September 1990, Atlanta was selected to host the 1996 Olympic Games to great fanfare and press coverage. The bidding process for the Paralympic Games, however, was separate, and the host for 1996 remained up in the air. At the time, the Paralympics did not have an audience base in the U.S. comparable to the Olympics. Many people outside of the disabled community were just learning the terms, “Paralympic” and “Paralympian.” The freshly signed ADA helped draw new attention to the question of future Paralympic plans.

“People understand what used to be an invisible minority is one much larger than everybody had realized. …The timing of this event in Atlanta could not be better.”

Advocates in Atlanta assembled to draft a plan for securing the Games. The international Paralympic community was interested in continuing the momentum set in Seoul by hosting Olympic and Paralympic Games at the same site, as the alignment elevated the profile of the event and drew new awareness. However, uncertainty about funding and logistics meant that Atlanta had to work for it. Early advocates formed the Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee (APOC). It included Andy Fleming, chairman of the U.S. Paralympic Task Force; Al Mead, a gold medalist at the 1988 Paralympic Games in Seoul; Harald Hansen, chairman of First Union National Bank of Georgia; and representatives of Shepherd Spinal Center.

By summer 1991, APOC members were in negotiations with the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG). Paralympic organizers presented their Olympic counterparts with plans to make Atlanta the host city for both events. They hoped the larger Olympic Games could underwrite or at least assume much of the costs and planning efforts.

However, the bid processes for the Paralympic and Olympic Games were quite separate, and Atlanta Olympic organizers had planned for only a very specific event scope. As a result, Olympic organizers were unable to assume the additional fundraising and planning needed for the additional event. Adjusting budgets and proposals over the next few months, APOC came to a deal with ACOG. The Olympic organizers agreed to share venues and provide event support services, thus confirming that Paralympic events would have space in Atlanta and enabling APOC to move forward with a proposal to the International Paralympic Committee.

Submitting Atlanta’s Bid for the 1996 Paralympic Games, Lynne Harty (Siler), photographer, Tignes, France, March 29, 1992, Courtesy Barb Trader

In March 1992, members of APOC travelled to Tignes, France, to officially present their bid for the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta. The bid presentation coincided with the 1992 Winter Paralympic Games in Tignes-Albertville. It was successful. On March 31, 1992, a headline on page A9 of Atlanta Constitution read: “It’s Atlanta Again.”

APOC members and supporters took on a big fundraising effort to gain revenue for what they planned as the world’s second largest sporting event in 1996. With major funding support from the Olympic organizers unavailable, Alana Shepherd of the Shepherd Center led the charge. The Shepherd Center donated a significant amount to the budget, provided staffing offices for the organizers, and Alana took on the big asks for corporate sponsorships.

Due to Olympic sponsorship protections, Paralympic organizers were required to prioritize sponsorship deals with existing Olympic sponsors. Provided with category exclusivity, sponsors who declined funding for the Paralympics could prohibit Paralympic organizers from soliciting funding from any product competitors. Alana Shepherd deemed the companies that did not support and blocked organizers from approaching competitors the “Sinful Six,” a shaming that gained traction in the press at the time.

Despite hurdles, sponsorship was a major source of revenue for the Games. Atlanta’s Paralympic Games, in fact, were the first to acquire significant corporate sponsorships. The initial projected budget for the Paralympic Games was around $40 million. When all was said and done, the Games cost about $84 million. A little more than $20 million was provided through federal funding. The rest came mostly from sponsorships, donations, ticket sales, broadcast fees, merchandise, and other concessions.

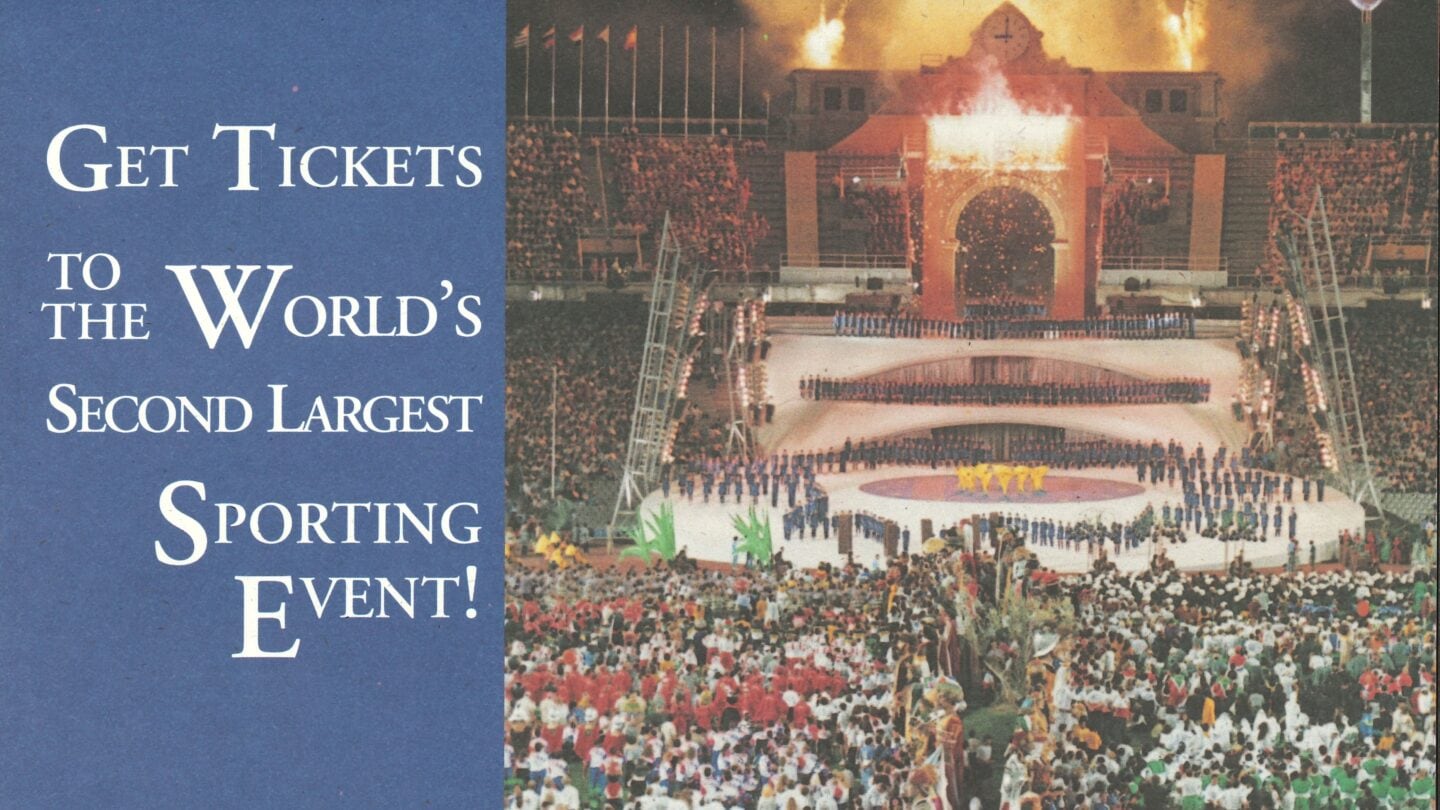

“Get Tickets to the World’s Second Largest Sporting Event” Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee, 1996. 1996 Olympic Games Subject Files – Paralympics, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The Second Largest Sporting Event of 1996

The Paralympic Games in Atlanta opened on August 16, 1996, and closed on the 25th. The sports schedule was complemented by programs and events that took place throughout August 1996. Those represented various facets of the Paralympic Movement’s mission, including physical achievement and advocacy for social inclusion. Atlanta hosted the world’s first Cultural Paralympiad with arts programs, exhibitions, and more.

The week before the Opening Ceremony, Paralympic organizers put on the Third International Paralympic Congress, a five-day conference that brought disability rights advocates, activists, and professionals. Arriving from all corners of the world, participants discussed solutions to issues facing the disability community. Topics included access to sports opportunities and issues of unemployment. The congress even included a Disability Film Festival. The festival showcased dozens of new films that featured disabled individuals in leading roles and affirming depictions of disability.

“A Triumph of Human Spirit” commemorative video, International Paralympic Committee and United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee September 1996. Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Opening and Closing Ceremonies for the Games featured celebrity appearances, performances, and theatrical productions. Christopher Reeve served as the emcee for the event and audiences were treated to appearances and performances by Aretha Franklin, Liza Minnelli, and others. With Muhammad Ali’s memorable cauldron lighting top of mind for viewers, the Paralympic Games had to make a splash. Through a feat of strength, Paralympian Mark Wellman hoisted himself up the side of the cauldron with mountain climbing gear to relight the fire.

Wellman’s climb kicked off a schedule of 19 sporting events. Nearly 4,000 athletes from 104 countries competed. Just like in the Olympic Games, Paralympic events change from year to year as sports are added or removed from the schedule. In 1996, fans could watch standards, such as swimming or track and field, or learn less-familiar sports, including goalball, lawn bowl, or wheelchair fencing. Over the duration of the Games, athletes broke 269 world records.

Blaze the Phoenix, Mascot of the 1996 Paralympic Games Stuffed animal, Dakin, Woodland Hills, California, circa 1996. Gift of Dr. David Apple, 2019

Audiences across the U.S. watched Paralympic events on television for the first time. Some followed along on the first official Paralympic website, which received about 120,000 hits per day. And nearly 400,000 people bought tickets and attended in person. Ticket sales were helped by a popular marketing campaign with a slogan, “What’s Your Excuse” (created by Atlanta agency BrightHouse) that appeared on television and in print.

The popularity of Atlanta’s Paralympic Games was obvious from more than just ticket sales and broadcast data. Blaze, the mascot for the Games, gained a solid fan base. The colorful phoenix bird received more favorable press than its Olympic friend Izzy. Designed by artist Trevor Irvin, Blaze was recognizably connected to Atlanta’s traditional symbol, the phoenix. Souvenirs in all the popular varieties of the time sold by the masses: t-shirts, playing cards, water bottles, and of course pins.

“What’s Your Excuse” commercial | BrightHouse | Crawford Communications, May 11, 1995 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

A Continuing Legacy

The 1996 Paralympic Games made strides for the Paralympic platform, engaged in activating a new era of U.S. disability rights, and made a strong case for closer unity and parity between the Olympic and Paralympic organizing agencies.

Bigger-than-before marketing efforts, combined with new spotlight on the disability community, brought more visibility to Atlanta than to past Paralympic hosts. Yet the Games left tangible legacies as well. Stadiums built for the Olympic Games in Atlanta were some of the first major U.S. public facility construction projects to incorporate ADA’s legislation on architecture and accessibility. Many disability rights advocates and Paralympic organizing committee members in Atlanta ensured that architects and construction teams met new standards and exercised compliance. These efforts shaped public understanding of truly accessible design in big arenas and venues.

On the individual level, organizers of the Games took on issues of widespread unemployment in the disability community and continued the practice of expanding inclusivity. APOC advocated for Games sponsors to consider their own actions related to the disability community. Several companies, including Randstad and The Home Depot, initiated employment placement initiatives for disabled people. They even recruited from the Paralympian community. Atlanta’s Games continued the practice of expanding inclusivity and were the first Games to include participants with intellectual disabilities.

The successes of Atlanta’s Games were recognized within the international Olympic and Paralympic communities and prompted lasting change. As a result, Paralympic and Olympic organizers committed to work closely together for the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia. That commitment became an official agreement between the International Olympic Committee and the International Paralympic Committee after the Games in Sydney. Recently, Olympic and Paralympic Games use the same torch, their torch relays share the same flame, and their mascots, logos, and medals are closely related. The “One City, One Bid” agreement exists for Games scheduled through the end of the 2020s, ensuring the Paralympic Games have a path to greater equity. In 2019, the name of the U.S. governing committee was updated to the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee. This is the first Olympic Committee in the world to include the word “Paralympic” in its name.

Additional. Resources.

1996 Paralympic History

“Atlanta 1996 Paralympic Games”

International Paralympic Committee

A Triumph of the Human Spirit: 1996 Atlanta Paralympic Games

Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee, 1996

“Legacy Lives on from when Atlanta Hosted the Paralympic Games 20 Years Ago”

Saporta Report

Maria Saporta

August 15, 2016

“Welcoming the Disabled, Atlanta Lets the Games Begin, Again”

The New York Times

Ronald Smothers

August 15, 1996

Paralympic History

“Access for All: The Rise of the Paralympic Games”

Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health

John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold

May 1, 2007

Paralympic Games Explained

Ian Brittain

Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2016

“History of the Paralympic Movement”

International Paralympic Committee

“IPC Highlights from the First 25 Years”

International Paralympic Committee

“The Paralympic Games and 60 Years of Change (1948–2008): unification and restructuring from a disability and medical model to sport-based competition”

Sport in Society

David Legg and Robert Steadward

2011

U.S. Disability History

Disability History

Smithsonian, National Museum of American History

“Disability History: The Disability Rights Movement”

National Park Service

Disability History of the United States

Kim E. Nielsen

Beacon, 2020

“Disability Rights Movement”

New Georgia Encyclopedia

Matthew Darby and Aisha Yaqoob

November 21, 2016

Georgia Disability History Collection Finding Aids

Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies

University of Georgia

“How the Americans with Disabilities Act Transformed a Country”

National Geographic

Amy McKeever

July 30, 2020

Major support of this exhibition has been generously provided by the James M. Cox Foundation, Marine and John Fentener van Vlissingen, Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, The Coca-Cola Company, Martha and Billy Payne, The UPS Foundation, Martie and Dennis Zakas, and The Rich Foundation.