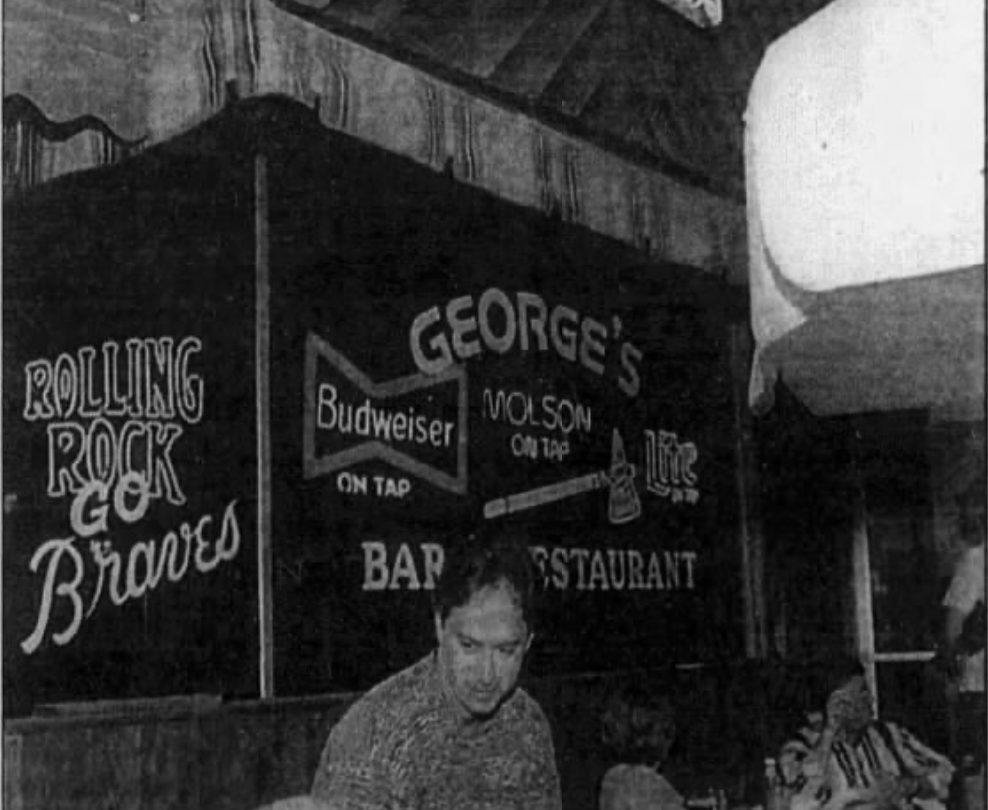

Businesses by the intersection of Virginia and Highland Avenues, Atlanta, Georgia. Moe’s and Joe’s and also Siegel’s Kosher Delicatessen, which George Najour later bought and turned into George’s Bar & Restaurant, can be seen. 1947. Courtesy of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Welcome to Virginia-Highland—or VaHi, as locals affectionately call it. Nestled in the heart of Atlanta, the neighborhood is bordered by Ponce de Leon Avenue to the south, Druid Hills to the east, Midtown and Piedmont Park to the west, and Morningside to the north.[1] Strolling down North Highland Avenue, past charming craftsman bungalows and brick storefronts shaded by century-old dogwoods, you’ll feel the character of a neighborhood that’s been charming Atlantans for over a century. Join us on a bar crawl through four legendary establishments: Atkins Park (est. 1922), Moe’s & Joe’s (1947), George’s Bar & Restaurant (1961), and Neighbor’s Pub (1985). More than just bars, these institutions have served as gathering places, landmarks, and cornerstones of the Virginia-Highland community across generations.

Early History

Long before there were bungalows and brick bars, this land belonged to the Muscogee (Creek) people—until a series of 19th-century land cessions and forced removals dispossessed the Muscogee of their land, clearing the way for white settlement under Georgia’s land lottery system, a state-run program that redistributed Indigenous land to white settlers through random drawings. [2]

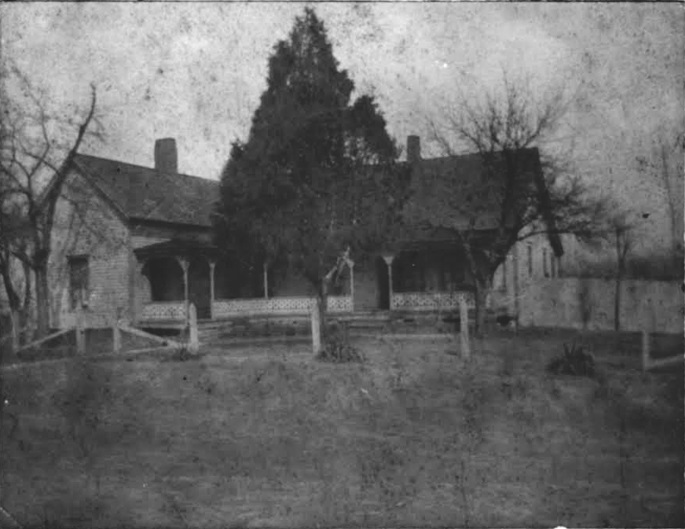

One such lottery winner, War of 1812 veteran William Zachry, claimed a 202.5-acre tract of land in the present location of the Virginia-Highland neighborhood in 1821. Zachry quickly sold the land in 1822 for $100 (approximately $2,700 today) to Richard Copeland Todd, a pioneer from Chester, South Carolina. [3] The following year, Richard Todd and his wife, Martha, established their homestead amid a forest of hickory, beech, and oak near present-day Ponce de Leon Place and Greenwood Avenue. The Todds farmed the land, raised five children, and lived out the rest of their lives on the property, eventually being buried at the nearby Todd family cemetery. [4]Their farmhouse stood for nearly a century before being destroyed by fire in 1910. [5]

A remnant of their legacy survives in Todd Road, one of the oldest streets in Atlanta. Originally a wagon trail connecting the Todd farm to the homestead of Richard’s brother-in-law, Hardy Ivy, the first European-American to settle in what is now downtown Atlanta in 1833, Todd Road still cuts a distinctive diagonal through the area’s otherwise orderly grid. Though now paved over, the small stretches of road that remain today offer a visible reminder of the area’s rural past. [6]

Through the late-nineteenth century, the area remained a patchwork of farmland and forest. Its high elevation, cool breezes, and proximity to the medicinal waters of Ponce de Leon Springs made it a popular retreat from city dwellers seeking health and respite. Productive farmland dominated the landscape, and grand country homes, like the Adair residence at the intersection of Virginia and North Highland Avenues, hosted lavish summer parties for Atlanta’s elite.[7] The area’s transformation began in the late 1880s with the arrival of the “Nine-Mile Circle” trolley, an electric streetcar line that would soon transform the quiet countryside into one of Atlanta’s first streetcar suburbs.

Birth of A Streetcar Suburb

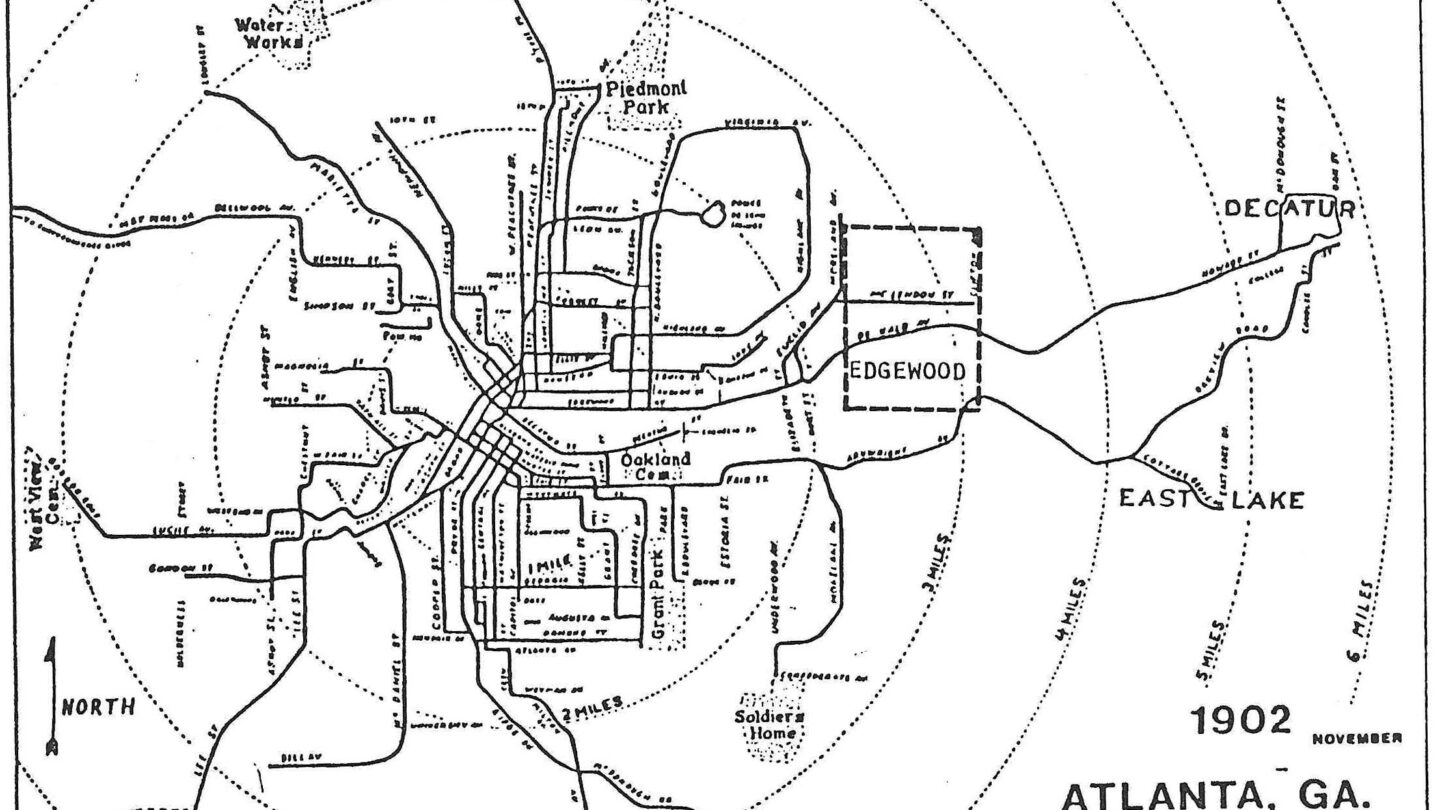

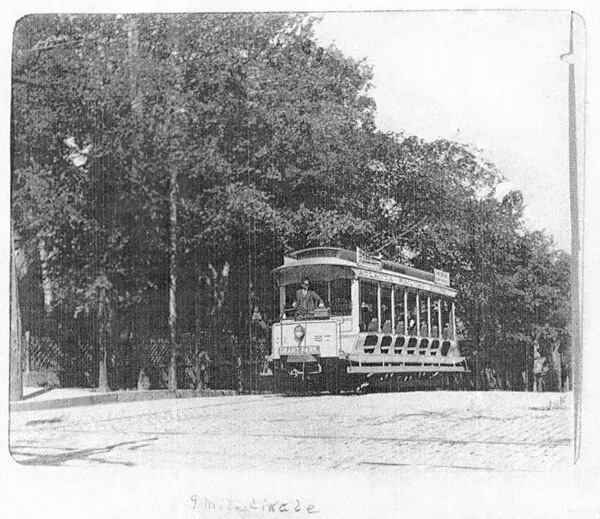

While horse- and mule-drawn trolley cars had operated in Georgia for decades, the electrically propelled streetcar was a new and exciting innovation. First proven successful in other cities—and locally by Joel Hurt’s Atlanta & Edgewood Street Railroad Company in August 1889, this innovation quickly sparked competition.[8] Later that same year, the Fulton County Street Railroad Company, led by Georgia Railroad executive Richard Peters and real estate developer George W. Adair, launched Atlanta’s second electric trolley system. Known as the “Nine-Mile Circle”, its route began downtown at Broad and Marietta Streets, ran north along Broad to Peachtree Street, then turned east onto Houston Street (now John Wesley Dobbs Avenue). From there, it followed Highland Avenue north to Virginia Avenue, curved west along Virginia, and turned south onto Boulevard (now Monroe Drive). It then looped back up to Highland and returned downtown via Houston and Peachtree, forming a complete circuit.[9]

For just five cents round-trip, city dwellers could escape to the wooded northeastern section of the city, which quickly became a popular destination for weekend picnickers.[10] In the 1890s, it was common for picnic groups to charter a trolley car, spread lunch in the woods and return to the city at dusk. On Sunday afternoons the trolleys were so crowded that men and boys hung on the steps outside the cars.[11]

As the Nine-Mile Circle brought reliable transportation to this rural area, developers rapidly bought and subdivided land.[12] Between 1904 and 1927, at least 18 subdivisions were laid out in Virginia-Highland, with the bulk of development occurring from 1905 to 1936.[13] The neighborhood’s grid layout was no accident. In fact, it was carefully designed to maximize access to trolley stops, since proximity to the line often determined property values. Some of the neighborhood’s oldest homes can be found along the trolley lines.[14] Small commercial blocks also sprang up just steps from trolley stops to capitalize on both trolley riders and neighbors alike. The Nine-Mile Circle’s path remains visible today in the distinctive curves at key intersections—most notably the gentle arc where North Highland and Virginia Avenues meet. Far from an aesthetic flourish, these wide turning radii were designed to accommodate the streetcars. A similar curve also exists at the intersection of Monroe Drive and Virginia Avenue today as well.[15]

To maintain the trolleys, service barns were constructed near the intersection of Virginia Avenue and Monroe Drive. These long, industrial buildings housed trolleys while they were undergoing repairs. Well-suited for long vehicles, they were later repurposed by MARTA as bus maintenance facilities until their demolition in 1988.[16]

The new subdivisions offered affordable single-family homes to a growing middle class of white professionals, salesmen, and shopkeepers, alongside a strong immigrant population from the Middle East, Greece, and Eastern Europe, who established local businesses.[17] Yet while diversity thrived in some aspects, Black Atlantans were barred from purchasing property in Virginia-Highland, as most developers included restrictive racial covenants as a condition of purchase.[18]

Architectural variety flourished. The Craftsman bungalow—Georgia’s most popular early 20th century home style—dominated the landscape, with its clipped-gable front porticos, exposed rafters, knee braces, grouped windows, and Doric columns. English Vernacular Revival cottages, Colonial Revival homes, American Foursquare, and Mediterranean-style houses and Neoclassical designs also proliferated, creating a rich architectural tapestry.[19] As demand for housing grew, particularly after World War I, developers added apartment buildings to the neighborhood. Between 1927 and 1937, the number of apartment buildings in Virginia-Highland increased from six to more than 23. These housed middle-class white tenants—salesmen, insurance agents, bookkeepers, and shopkeepers—who worked in the bustling commercial corridor. The garden-styleColonnade Court Apartments, the St. Charles, and the Wilsonian were among the earliest. The Briarcliff Hotel, a nine-story luxury building opened by Asa Candler Jr. at the corner of North Highland and Ponce de Leon avenues, offered an upscale alternative to single-family homes. All four of these historic buildings still exist today.[20]

As the residential core matured, commercial growth followed. While a few small commercial establishments had clustered near the intersection of Virginia Avenue and North Highland Avenue, most commercial development at this intersection began in 1925. At the same time, commercial development had also begun to change the other areas along North Highland Avenue, including the portion near Atkins Park.[21] The nearby Ford Motor Company plant which opened in 1915 and the massive Sears and Roebuck distribution center, now Ponce City Market, built in 1926 on Ponce de Leon Avenue also provided steady employment for a large number of residents in the neighborhood and contributed to its continued growth.[22]

By the end of the 1920s, Virginia-Highland had largely completed its rapid transformation from farmland to a thriving streetcar suburb.Nearly all the large tracts of open land around Virginia-Highland had been developed and built on by 1936.[23] Unlike many other areas of Atlanta, Virginia-Highland saw relatively little change during the post–World War II boom. Only a handful of infill homes were added in scattered locations.[24]

Threats and Transformation: The Interstate Crisis

By the mid-1920s, the rise of the automobile fundamentally reshaped how Atlantans lived and traveled. As cars became more affordable and widespread, new subdivisions emerged farther from trolley lines.[25] The streetcar, once the lifeblood of Virginia-Highland, faded quietly from daily life. Bus lines and automobiles gradually replaced electric trolleys, and by the time the last streetcar rolled through Atlanta in 1949, few residents noticed.[26]

Though Virginia-Highland remained stable through the 1940s, the postwar suburban boom drained its population. Like many of Atlanta’s intown communities—Midtown, Inman Park, Grant Park, and West End among them—Virginia-Highland entered a prolonged period of decline. The rise of the automobile, the lure of the suburbs, the response to school integration, and the looming threat of a highway that was planned to cut through the neighborhood, prompted many families to leave.[27] As they left, many single-family homes were subdivided into apartments or rented out. Property values and incomes decreased. Commercial areas deteriorated as once-thriving neighborhood businesses shuttered, replaced by low-rent tenants such as pawn shops.[28] By the early 1970s, residents described a neighborhood seemingly trapped in irreversible decline—its houses decaying, its streets quiet, and its future uncertain.[29] Then came Virginia-Highland’s greatest existential threat: Interstate 485.

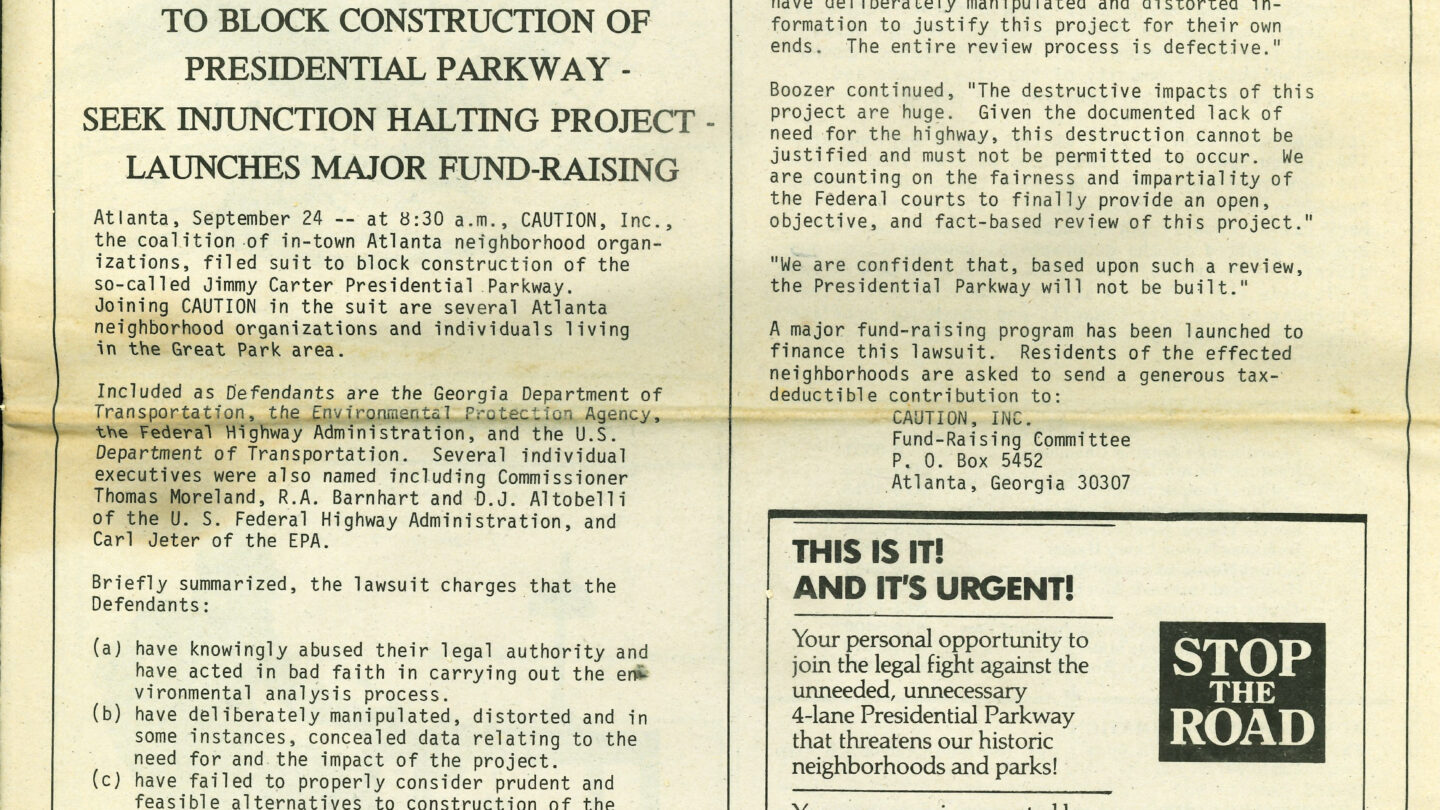

In the mid 1960s, the Georgia Department of Transportation proposed a six-lane freeway that would have cut directly through the heart of Virginia-Highland.[30] The proposed route ran north to south, threatening to bisect not only Virginia-Highland but also several other historic intown neighborhoods along the way.[31] The state began buying up properties along the proposed corridor, demolishing homes and marking many more for demolition.[32] But the community rallied and resisted. By 1971, a group of concerned residents organized the Virginia-Highland Neighborhood Association, giving the neighborhood both its name—drawn from the intersection of Virginia and North Highland Avenues—and a collective voice. Until then, the neighborhood lacked a formal identity. In fact, a pro-highway group had even claimed to speak for the neighborhood under the name “Highland-Virginia Civic Association.”[33] The new anti-highway association quickly joined forces with other neighboring civic associations across the city, forming a broad coalition of grassroots activists, homeowners, preservationists, and concerned citizens determined to stop the highway.[34]

At the same time, a new wave of young professionals and middle-class families began to move back into Atlanta’s intown neighborhoods. Attracted by the charm and affordability of the older homes—and later spurred on by the gasoline crisis of the 1970s—these “urban pioneers” began renovating neglected properties and reviving community life. Vacant storefronts and utilitarian businesses gave way to restaurants and boutique shops.[35] In Virginia-Highland, homeownership rose between 1972 and 1975, and property values increased by 20 to 50 percent. By 1972, the neighborhood launched its first “Bungalow Tour of Homes” to showcase renovation projects and galvanize support for preservation.[36]

This resurgence infused the anti-highway movement with new energy and leadership. In June 1975, local activist and future City Council member Mary Davis helped transform the neighborhood association into the Virginia-Highland Civic Association (VHCA), which would spearhead the fight against I-485. The VHCA evolved from the earlier neighborhood groups and coordinated legal challenges, public opposition, and political pressure to stop I-485. Years of sustained resistance paid off as the highway plant was ultimately abandoned. It was a landmark victory—not only for Virginia-Highland, but for grassroots urban preservation efforts across Atlanta.[37]

After the project was defeated, the Georgia Department of Transportation began disposing of properties it had acquired for the freeway’s right of way. Most of the lots were purchased for infill housing, except the land intended for the proposed Virginia Avenue exit.[38] Here, the 11 demolished home sites were transformed into a public park. Named for John Howell, a “well-known and well-loved” neighborhood activist who was instrumental in stopping the construction of the interstate, John Howell Memorial Park remains a well-trafficked recreational area.[39]

By all accounts, the revitalization that began in the 1970s and accelerated in the following decade stabilized Virginia-Highland and charted a new course for its future. What had once seemed like a neighborhood in terminal decline became a case study in grassroots preservation.

Four Taverns, One Historic Neighborhood

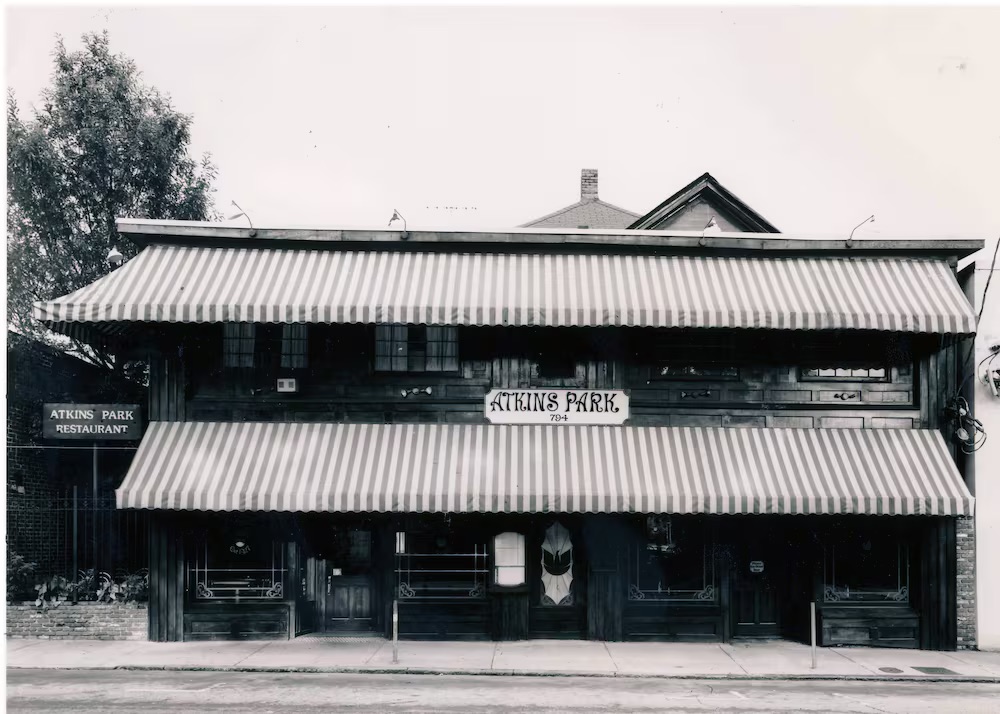

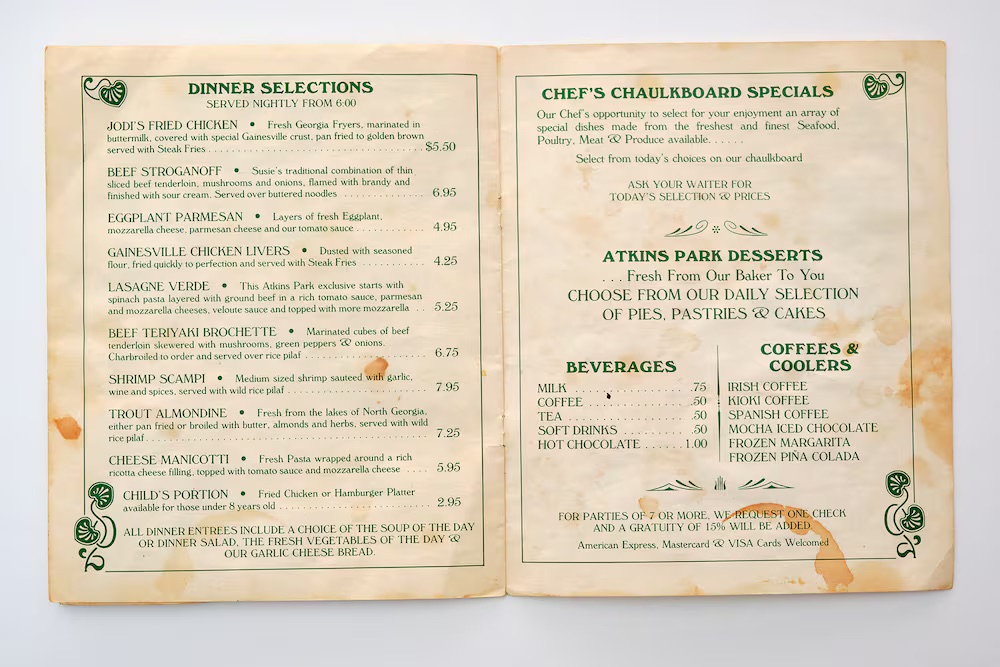

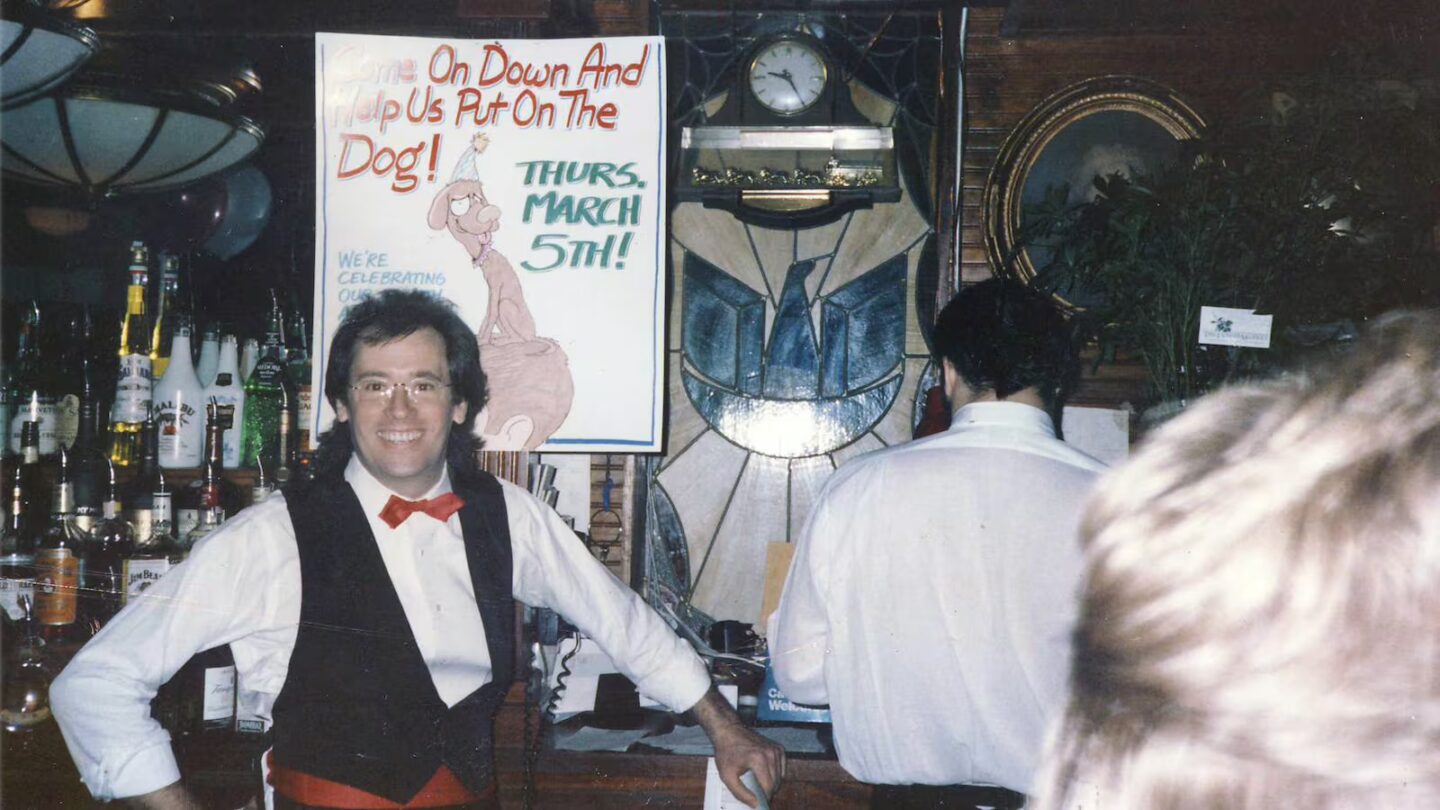

Atkins Park (Est. 1922) Atkins Park proudly holds the title of Atlanta’s oldest continuously licensed tavern.[40] Originally built as a private home around 1910, the structure was lifted twenty feet in the 1920s to make way for a delicatessen below, which opened in 1922. After prohibition ended, the deli began serving beer and sandwiches, securing a beer and wine license in the early 1930s that it has held ever since (the liquor license was added in 1980).[41] Eventually, “Delicatessen” was dropped from the name and Atkins Park became a beloved neighborhood pub. The bar was a popular hangout for decades and continued plugging along in the 1970s as a hangout for painters and construction workers. In 1983, Warren Bruno—an energetic family man with a passion for the community—revitalized the space, transforming it into the lively bar and restaurant it is today. The interior still features its original copper ceiling tiles and tiled floor dating back to its deli days over 103 years ago.[42] Since Bruno’s passing in 2012, his wife Sandra Spoon has carried on the legacy, keeping Atkins Park a cornerstone of the southern end of Highland Avenue.[43]

Moe’s & Joes (Est. 1947)

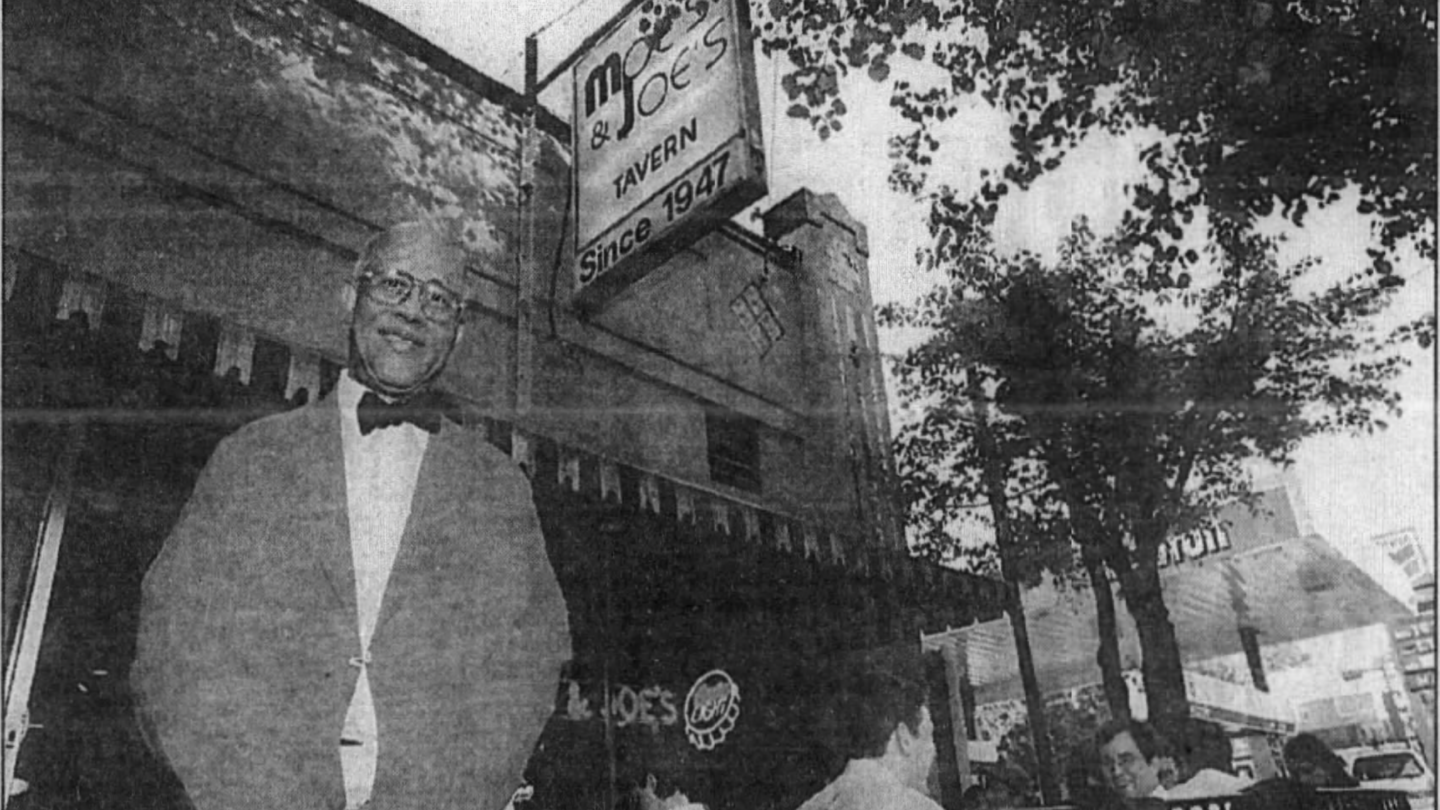

Brothers Moe and Joe Krinsky returned from World War II and opened Moe’s & Joe’s in 1947. At the time, the bar sat just inside Fulton County, conveniently across the county line from what was then a dry DeKalb County. They owed much of their early success to drawing thirsty DeKalb residents across the border. Specializing in cold beer, hot dogs, and hamburgers, the bar quickly became a hangout for neighborhood residents and generations of Emory students.[44]

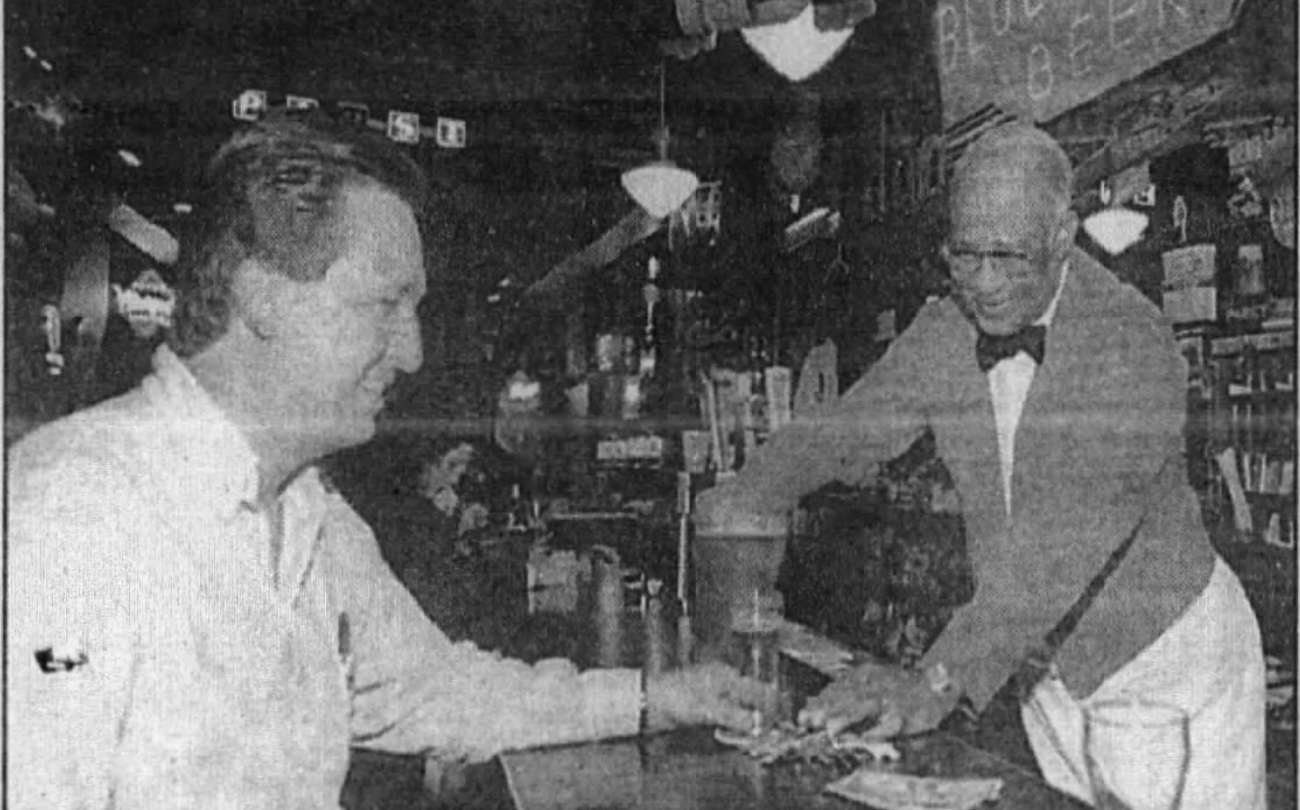

In 1948, they hired their first employee, the enormously popular Horace McKinnie. Always dressed in a bow tie, suspenders, and formal jacket, McKinnie, with his warmth, reliability, and signature style would go on to work at Moe’s & Joe’s for an astonishing 52 years. A mural of him adorning the south side of the building now honors his legacy.[45]

Over the years, Moe’s & Joes” expanded, knocking a hole through a wall to create an archway into what was once a bar next door called The Cavern.[46] The result was a larger, livelier space that retained its original charm, wooden booths, vintage cash register, and smoke-stained wallpaper.

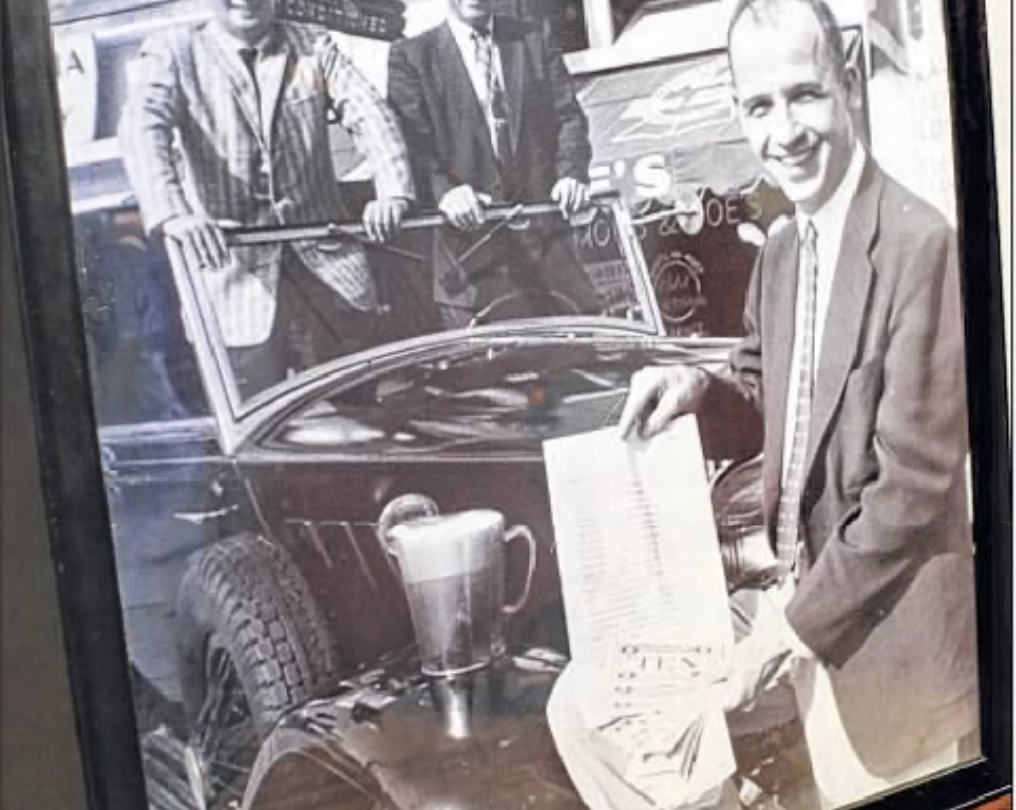

Among the bar’s most colorful tales is when a regular customer once traded his 1947 Rolls-Royce to the Krinsky brothers in exchange for 1,700 pitchers of beer. The brothers printed up fake dollars for the deal, and—according to family lore–the customer redeemed pitcher-by-pitcher, until every last one was gone.[47]

George’s Bar & Restaurant (Est. 1961)

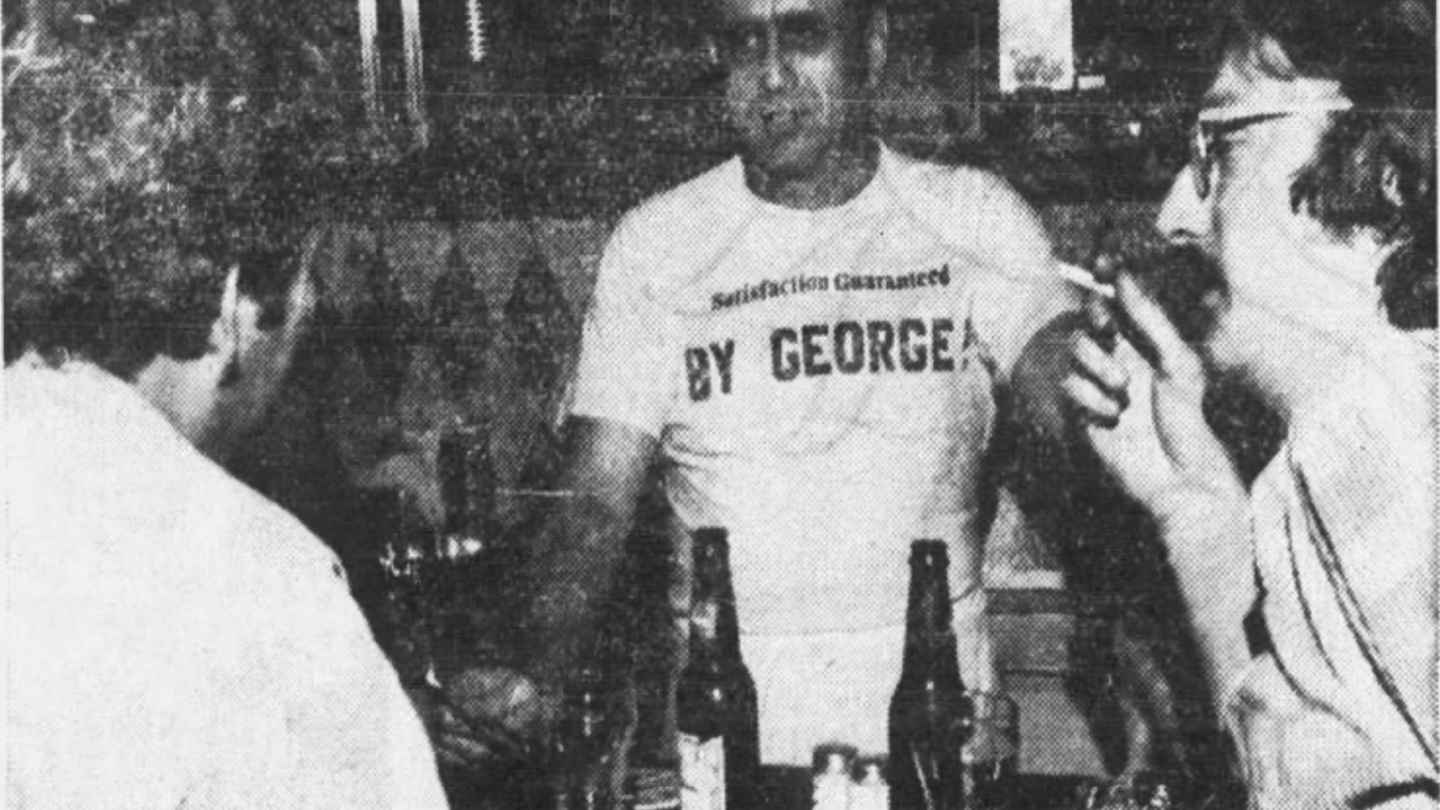

George Najour, a WWII veteran and former minor league baseball player, took a chance on the sleepy Virginia-Highland neighborhood in 1961. He purchased Seigel’s Delicatessen and renamed it George’s, combining a Middle Eastern grocery and deli in the front with a bar in the back, serving cold beer and sandwiches.[48] George positioned himself behind the bar, not just running a business but building a community. They “didn’t have a home,” he later said, “so I had to build a home for them.”[49]

Early advertisements in 1966 promoted “Greek & Arabic Foods,” reflecting Najour’s Lebanese heritage and the neighborhood’s growing immigrant presence.[50] By the 1970s, George’s had become a beloved local hangout. A 1977 article described the bar’s famously graffiti-covered men’s room wall—so thoroughly scribbled with messages that George eventually nailed a tin sheet over it. Loyal customers, “out of fondness for Najour,” brought special pens and continued to write on the tin. “They love him, and he loves them,” the article concluded.[51]

Known for its easy going atmosphere, George’s adopted the slogan “no cover, no minimum,” and became, in the words of one profile, “the nerve center for the politically active.”[52] George was said to know most customers by name, and treated those he didn’t know as if he did.[53] At closing time, Najour famously blew “Taps” with his mouth to signal last call.[54]

In 1983, with the help of his son, G.G. Najour, George’s added a kitchen and rolled out a limited menu that included the now-famous George’s burger, as well as some appetizers, salads, and other items. The business was officially renamed George’s Bar & Restaurant. As the bar underwent renovations, an article went out in the Atlanta Constitution assuring nervous regulars: “The beer will still be the coldest in town, an opinion corroborated by nine out of 10 customers.”[55]

Neighbor’s Pub (Est. 1985)

A true late-night staple of Virginia-Highland, Neighbor’s Pub has been serving up cold drinks, good food, and fun times and since 1985.[56] Neighbor’s quickly became more than just a bar—it became a hub for fostering community. In 1995, Neighbor’s supported Atlanta’s beautification efforts before the 1995 Olympic games, delivering free lunches to volunteers cleaning vacant lots on Greenwood Avenue.[57] It also played a pivotal role in Georgia’s craft beer scene, becoming the first bar to put SweetWater Brewing Company on tap around the early 2000s, helping launch what is now one of the Southeast’s largest craft breweries.[58]

Virginia-Highland Today: A Thriving Historic Hub

Virginia-Highland remains one of Atlanta’s most vibrant neighborhoods, blending historic charm with dynamic growth. Its tree-lined streets, classic bungalows, and proximity to the BeltLine, Piedmont Park, and lively shops and restaurants make it a destination for locals and visitors alike. From its early 20th-century roots to the activism that saved it from destruction, the community has continually reinvented itself while honoring its past. The enduring presence of iconic local bars like George’s, Moe’s & Joe’s, Atkins Park, and Neighbor’s Pub reflects the neighborhood’s deep sense of identity and community spirit.

Atlanta History Center will host its Virginia-Highland Party with the Past with a bar crawl across these four historic bars on June 25. Join us to learn more about the history of this vibrant neighborhood.

Ambrose, Andy. Atlanta: An Illustrated History. Hill Street Press, 2003.

Atkins Park. “Atkins Park.” Accessed June 17, 2025, https://www.atkinspark.com/.

Atlanta-Midtown. “The John Howell Park Project.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20160323214953/http://atlanta-midtown.com/nonprofit/howellpark/.

Carlisle, Lola, and Jack White. Virginia-Highland. Arcadia Publishing, 2018. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=AcJHDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Crenshaw, Holly. “Early Spring Cleaning.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 12, 1995. https://www.newspapers.com/image/402954562/?match=1&terms=%22Neighbor%27s%20Pub%22.

Garrett, Franklin M. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of People and Events, Vol. I, 1820s–1870s. University of Georgia Press, 1969.

Garrett, Franklin M. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of People and Events, Vol II, 1880s–1930s. University of Georgia Press, 1969.

George’s Restaurant. “History.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://www.georgesbarandrestaurant.com/history.

Gigantino, Jim. “Land Lottery System.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Sep 28, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/land-lottery-system/.

Graham, Keith. “Cedar Outside Won’t Change George’s Food Inside.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 4, 1982. https://www.newspapers.com/image/399058428/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22.

“Greek & Arabic Foods.” The Atlanta Journal, November 20, 1966. https://www.newspapers.com/image/969836065/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22.

Hall, Van. “The Interstate That Almost Was.” Morningside‑Lenox Park Association Newsletter 22, no. 3 (Fall 2003). PDF file. Accessed June 17, 2025. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/interstate_that_almost_was.pdf.

Hansberger, Angela. “A Helping of History.” 17th South, September 2017. https://www.17thsouth.com/a-helping-of-history/.

Henry, Derrick. “George Najour, 81, Owned Atlanta Tavern.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 2, 2002. https://www.newspapers.com/image/422934182/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22.

Hill, Denzel H., Jr. “A Night With George and His Regulars.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1977. https://www.newspapers.com/image/398855106/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22.

“History of Virginia-Highland.” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf.

Hobson-Pape, Karri, and Lola Carlisle. Virginia-Highland. Arcadia Publishing, 2011. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Keen, Raymond. “Todd Road.” History Atlanta, November 11, 2014. http://historyatlanta.com/todd-road/.

Kline, Emily. Virginia-Highlands Historic District. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf.

Lee, Conor. “Atlanta Fire Station No. 19.” History Atlanta. April 22, 2014. https://historyatlanta.com/fire-station-19/.

Merrill, Linda. “History of Virginia-Highland.” https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/HistoryVaHi1.pdf.

Moe’s & Joe’s. Menu. Viewed by author, May 26, 2025.

Neighbor’s Pub. “Neighbor’s Pub.”Accessed June 17, 2025. https://neighborsatlanta.com/.

Powell, Kay. “Moe Krinsky, Created Landmark.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 26, 2006. https://www.newspapers.com/image/422930782/?match=1&terms=%22Moe%27s%20%26%20Joe%27s%22.

“Spring: Get to know Atlanta on neighborhood walking tours.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 17, 1990. https://www.newspapers.com/image/400052030/?match=1&terms=%22Moe%27s%20%26%20Joe%27s%22.

SweetWater Brewing Company. “About Swetwater.” Accessed June 17, 2025, https://www.sweetwaterbrew.com/about/.

Townsend, Bob. “Atlanta Classics: Virginia-Highland Landmark Atkins Park Has Stood the Test of Time.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 21, 2022. https://www.ajc.com/things-to-do/atlanta-restaurant-blog/atlanta-classics-virginia-highland-landmark-atkins-park-has-stood-the-test-of-time/7KFB2WOXKRBTTGJM7IC535DMJM/.

Townsend, Bob. “Mixing It Up at Moe’s and Joe’s.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 30, 2014. https://www.newspapers.com/image/424510225/?terms=Moe%27s.

Townsend, Bob. “Tapping into Success.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 2006. https://www.newspapers.com/image/422809711/?match=1&terms=%22Neighbor%27s%20Pub%22.

Weiss, Joey. “The Wild History of Atkins Park Restaurant & Bar, A Neighborhood Icon.” Atlanta Eats, October 3, 2023. https://www.atlantaeats.com/blog/atkins-park-neighborhood-icon/.

Woolner, David. “Deli Meeting Helps Bridge Political Split.” The Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1978. https://www.newspapers.com/image/972878555/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22.

Notes

[1] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 5. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[2] Conor Lee, “Atlanta Fire Station No. 19,” History Atlanta, April 22, 2014, https://historyatlanta.com/fire-station-19/; Jim Gigantino, “Land Lottery System,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Sep 28, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/land-lottery-system/

[3] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 22. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[4] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 9. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[5] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 22. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[6] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf; Linda Merill, “History of Virginia-Highland,” 1-2. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/HistoryVaHi1.pdf; Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 17. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false; Raymond Keen, “Todd Road,” History Atlanta, November 11, 2014. http://historyatlanta.com/todd-road/

[7] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[8] Franklin M. Garrett, Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of People and Events, 1880s-1930s (University of Georgia Press, 1969), 191. 189-191

[9] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf; Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 23. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf; Franklin M. Garrett, Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of People and Events, 1880s-1930s (University of Georgia Press, 1969), 191.

[10] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 23. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[11] Franklin M. Garrett, Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of People and Events, 1880s-1930s (University of Georgia Press, 1969), 191.

[12]“History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[13] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 16. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[14] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 5-6. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[15] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf; Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 23. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[16] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf; Lola Carlisle and Jack White, Virginia Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011),13.https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[17] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[18] Lola Carlisle and Jack White, Virginia-Highland (Arcadia Publishing, 2018), 7, https://books.google.com.na/books?id=AcJHDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

[19] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 23. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[20] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 24-5. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[21] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[22] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 24-5. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[23] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[24] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 24-5. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[25] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 20, 26. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf;

[26] Andy Ambrose, Atlanta: An Illustrated History (Hill Street Press, 2003), 146; Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 27. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf; Lola Carlisle and Jack White, Virginia-Highland (Arcadia Publishing, 2018), 13, https://books.google.com.na/books?id=AcJHDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

[27] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[28] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[29] “Spring: Get to know Atlanta on neighborhood walking tours,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 17, 1990, https://www.newspapers.com/image/400052030/?match=1&terms=%22Moe%27s%20%26%20Joe%27s%22

[30] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[31] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[32] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 27. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[33] Van Hall, “The Interstate That Almost Was,” Morningside-Lenox Park Association, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Fall 2003) 6, https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/interstate_that_almost_was.pdf

[34] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

[35] Karri Hobson-Pape and Lola Carlisle, Virginia-Highland, (Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 7. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=M37J3BPg-zcC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false; Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 27-8. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[36] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 27. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[37] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 13. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf; “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf

[38] Emily Kline, “Virginia-Highlands Historic District,” United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, September 25, 2000, 27-8. https://vahi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/national_reg_historic_places_regstration_form.pdf

[39] “History of Virginia-Highland,” City of Atlanta, Department of Planning, Develop and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20040602180005/http://www.vahi.org/pdfs/history.pdf; “The John Howell Park Project,” Atlanta-Midtown, accessed June 17, 2025, https://web.archive.org/web/20160323214953/http://atlanta-midtown.com/nonprofit/howellpark/

[40] “Atkins Park,” Atkins Park, accessed June 17, 2025, https://www.atkinspark.com/

[41] Bob Townsend, “Atlanta Classics: Virginia-Highland Landmark Atkisn Park Has Stood the Test of Time,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 21, 2022, https://www.ajc.com/things-to-do/atlanta-restaurant-blog/atlanta-classics-virginia-highland-landmark-atkins-park-has-stood-the-test-of-time/7KFB2WOXKRBTTGJM7IC535DMJM/; Joey Weiss, “The Wild History of Atkins Park Restaurant & Bar, A Neighborhood Icon,” Atlanta Eats, October 3, 2023, https://www.atlantaeats.com/blog/atkins-park-neighborhood-icon/

[42] Angela Hansberger, “A Helping of History,” 17th South, September, 2017, https://www.17thsouth.com/a-helping-of-history/

[43] Lola Carlisle and Jack White, Virginia-Highland (Arcadia Publishing, 2018), 18, https://books.google.com.na/books?id=AcJHDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

[44] Moes & Joes, Menu, viewed by author May 26, 2025.

[45] Moes & Joes, Menu, viewed by author May 26, 2025.

[46] Bob Townsend, “Mixing It Up At Moe’s and Joe’s,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 30, 2014, https://www.newspapers.com/image/424510225/?terms=Moe%27s

[47] Kay Powell, “Moe Krinsky, Created Landmark,” The Atlanta Constitution, April 26, 2006, https://www.newspapers.com/image/422930782/?match=1&terms=%22Moe%27s%20%26%20Joe%27s%22

[48] Bob Townsend, “Mixing It Up At Moe’s and Joe’s,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 30, 2014, https://www.newspapers.com/image/424510225/?terms=Moe%27s; Keith Graham, “Cedar Outside Won’t Change George’s Food Inside,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 4, 1982, https://www.newspapers.com/image/399058428/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22; George’s Restaurant, History, accessed June 17, 2025, https://www.georgesbarandrestaurant.com/history

[49] Denzel H. Hill Jr., “A Night With George and His Regulars,” The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1977, https://www.newspapers.com/image/398855106/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[50] “Greek & Arabic Foods” The Atlanta Journal, November 20, 1966, https://www.newspapers.com/image/969836065/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[51] Denzel H. Hill Jr., “A Night With George and His Regulars,” The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1977, https://www.newspapers.com/image/398855106/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[52] Denzel H. Hill Jr., “A Night With George and His Regulars,” The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1977, https://www.newspapers.com/image/398855106/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22; Ann Woolner, “Deli Meeting Helps Bridge Political Split,” The Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/image/972878555/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[53] Denzel H. Hill Jr., “A Night With George and His Regulars,” The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1977, https://www.newspapers.com/image/398855106/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[54] Derrick Henry, “George Najour, 81, Owned Atlanta Tavern,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 2, 2002, https://www.newspapers.com/image/422934182/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[55] Derrick Henry, “George Najour, 81, Owned Atlanta Tavern,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 2, 2002, https://www.newspapers.com/image/422934182/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22; Keith Graham, “Cedar Outside Won’t Change George’s Food Inside,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 4, 1982, https://www.newspapers.com/image/399058428/?match=1&terms=%22George%27s%20Delicatessen%22

[56] “Neighbor’s Pub,” Neighbor’s Pub, accessed June 17, 2025, https://neighborsatlanta.com/

[57] Holly Crenshaw, “Early Spring Cleaning,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 12, 1995, https://www.newspapers.com/image/402954562/?match=1&terms=%22Neighbor%27s%20Pub%22

[58] Bob Townsend, “Tapping into Success” The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 2006, https://www.newspapers.com/image/422809711/?match=1&terms=%22Neighbor%27s%20Pub%22; “About Swetwater,”SweetWater Brewing Company, accessed June 17, 2025, https://www.sweetwaterbrew.com/about/