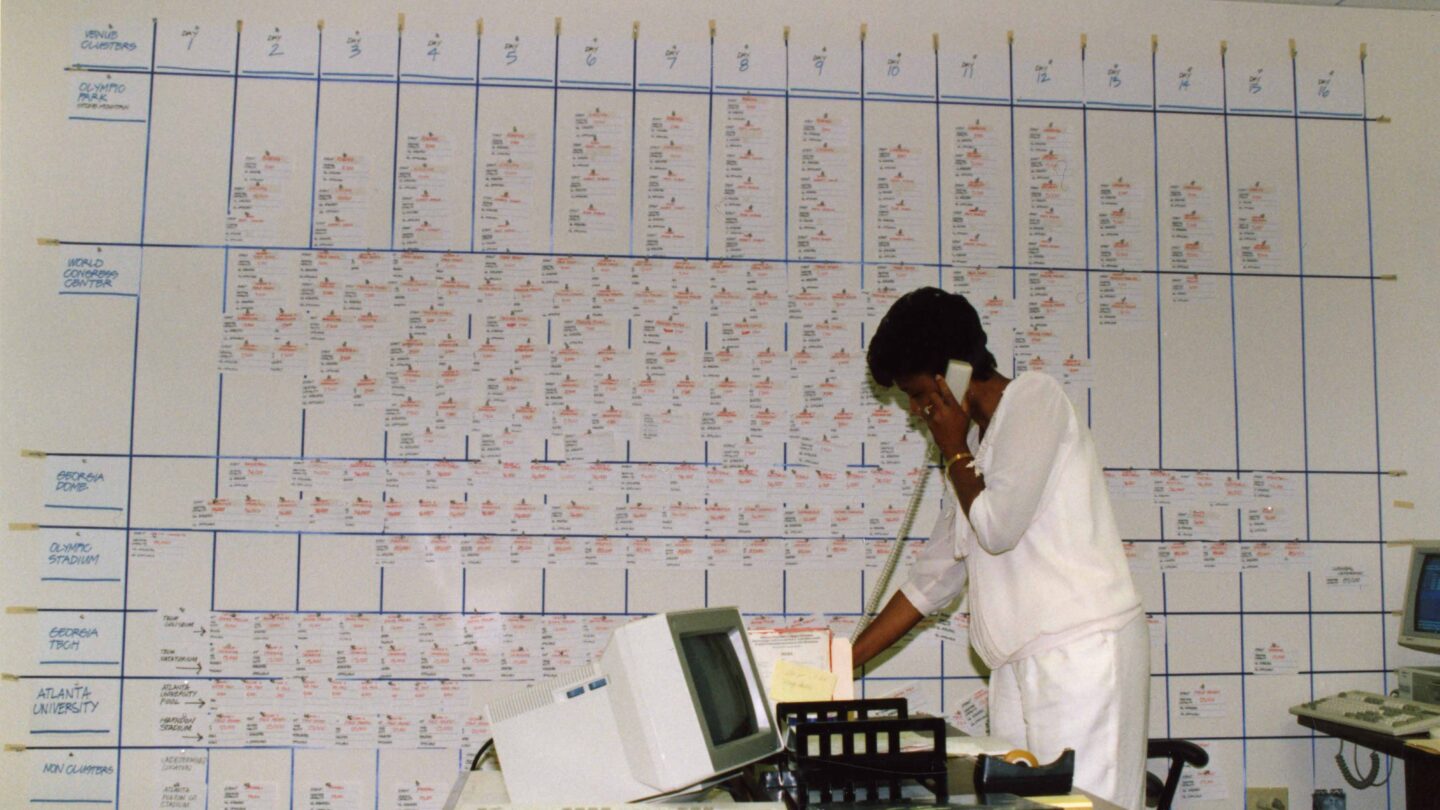

ACOG Staff Member in Office With Day-to-Day Games Schedule Board | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

By the 1990s, the digital revolution was in full swing. Personal computers were changing the way we worked, powering offices and quickly becoming accessible for U.S. households. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee’s “Information Management: A Proposal” hit desks at the European research center CERN aiming to develop a digital mesh to take advantage of interconnected computer networks used for science, research, and defense projects globally. His idea led to the creation of the World Wide Web. The Web’s capabilities and size snowballed during the decade, enabling individuals and companies to make use of a brand-new medium for connection, information, and business.

The use of cell phones also expanded in the ‘90s. The PDA—a predecessor for smart phones—was introduced. Innovations brought entertainment as well as convenience and interconnectedness. Computer graphics innovation improved the look of animated movies and video games. Nintendo 64 sold out on shelves everywhere after its 1996 release. And an old medium, the book, found a new place on the pages of an e-commerce site launched in 1995: Amazon.

The rush to be on the forefront of change is ever-present in the tech world, and the opportunities of the 1990s only increased the pace. The spotlight moved fast from new ideas to product launches to achievements. Innovators in the tech field sought interested audiences and media attention to help gain momentum for their projects in a sea of hungry competitors. In advance of the 1996 Olympic Games, Olympic organizers in Atlanta worked to capture some of this spotlight, using new technology to convince the world to select Atlanta and showcase the city as cutting edge and progressive—just as many host cities before them had done.

Innovations have been part of the Olympic Games since they were aligned with World’s Fairs and international expositions in the early 1900s. The Games are an enabler for hosts to display their nations’ technological advancements and prowess, companies to obtain funds for new projects, and innovations to receive widespread testing and attention. Past Olympic Games have highlighted major advances in broadcast technology, manufactured materials, and timing devices. By the late 1980s to 1990s, Olympic organizers had even more possibilities and media at their disposal.

Decades of fiber optic installation and experimentation provided the foundation for communication advancements. Players in the technology field, including academia and the corporate world, were looking for a forum for their equipment and projects. Atlanta’s Games benefited from this surge in interest, resources, and activity in new technology.

Virtual Venues

Partnering with researchers at Georgia Tech and a coalition of big telecommunications and technology companies, Atlanta’s Olympic organizers harnessed the impressive powers of burgeoning technology in the early stages of the city’s bid process.

Excerpt From Atlanta Organizing Committee’s Bid Presentation Video | Interactive Media Technology Center, Georgia Tech, 1989 | Courtesy Georgia Institute of Technology Library and Information Center, | Archives and Records Management Department

In the late 1980s, Georgia Tech’s then-president Pat Crecine pitched that researchers from the school’s Interactive Media Technology Center could create a special presentation to introduce the international delegates to an Atlanta of the future—an Atlanta of 1996. This was not a slideshow or video, but an immersive and interactive tour of how the city would accommodate the Games, complete with models of new venues and clips of athletes in action. It was a cutting-edge proposal for a time when virtual reality and computer-generated environments were not mainstream concepts.

To create the simulation, researchers combined an array of techniques and data—video footage, aerial photography, topographic data, digital models, computer graphics, and animation—into one multimedia production. Despite now seeming commonplace, “multimedia” was a new frontier in technology in the late 1980s. The idea of combining a variety of different media into one electronically delivered, interactive experience was only possible because of digital files—audio data, video data, photography, geographic information, and more—that could be interconnected in the digital world.

There’s a chance—more than a slim one and less than a sure thing— that Atlanta will become the center for a technology so important it is sure to change your world. The technology is called ‘multimedia.’

Georgia Tech’s project tested their own limits, but placed Atlanta apart from its Olympic bid competitors. To finish the unprecedented visual presentation, researchers used computers across Tech’s entire campus. They also used Georgia State University computer labs to help process the huge data files in time for Olympic bid meetings. And they made connections with big corporations on the forefront of multimedia work, including PIXAR and IBM.

The project resulted in a few versions of the presentation. The main experience pulled out all the stops for the Olympic bid presentation and required an elaborate set-up. There were three seven-foot-tall projection screens for the video content. The viewer could control the tour, flying from one proposed venue to another, by touching different buildings on a Lucite model of the city’s core.

One of the other versions resulted in a more compact arcade game-like experience. Users stepped up to the console and rolled a “track ball” to control their path through the Atlanta of 1996, flying through a representation of a premier city filled with new stadiums, parks, hotels, and convention centers. The interactive station was installed at SciTrek, Atlanta’s Science and Technology Museum, the summer before the Olympic bid. It attracted crowds of Atlantans and tourists to the museum, eager to experience the futuristic work of the candidacy process for themselves and try their hand at a track ball.

Atlanta Organizing Committee’s Exhibition Booth at 96th IOC Congress | Unidentified photographer, Tokyo, September 18, 1990 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The main presentation was first presented to International Olympic Committee (IOC) delegates in 1989 at a forum in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It was showcased again in full just a little over one year later at the 96th IOC Congress in September 1990 alongside more traditional booths set up by the five other candidate cities. The IOC members were wowed by the display of new technology. It was deemed Atlanta’s “secret weapon” by those who were involved in the bid process. And it solidified IOC’s reasoning that Atlanta would be an apt location to welcome the Olympic Games into its second century—a future-looking, innovative hub for the Centennial Games.

Atlanta Online

“Online” was a new venue for Atlanta’s Olympic committee and media outlets to contend with in the years prior to the summer of 1996. Partnerships in the technology field once again pushed organizers to try something new and cutting edge.

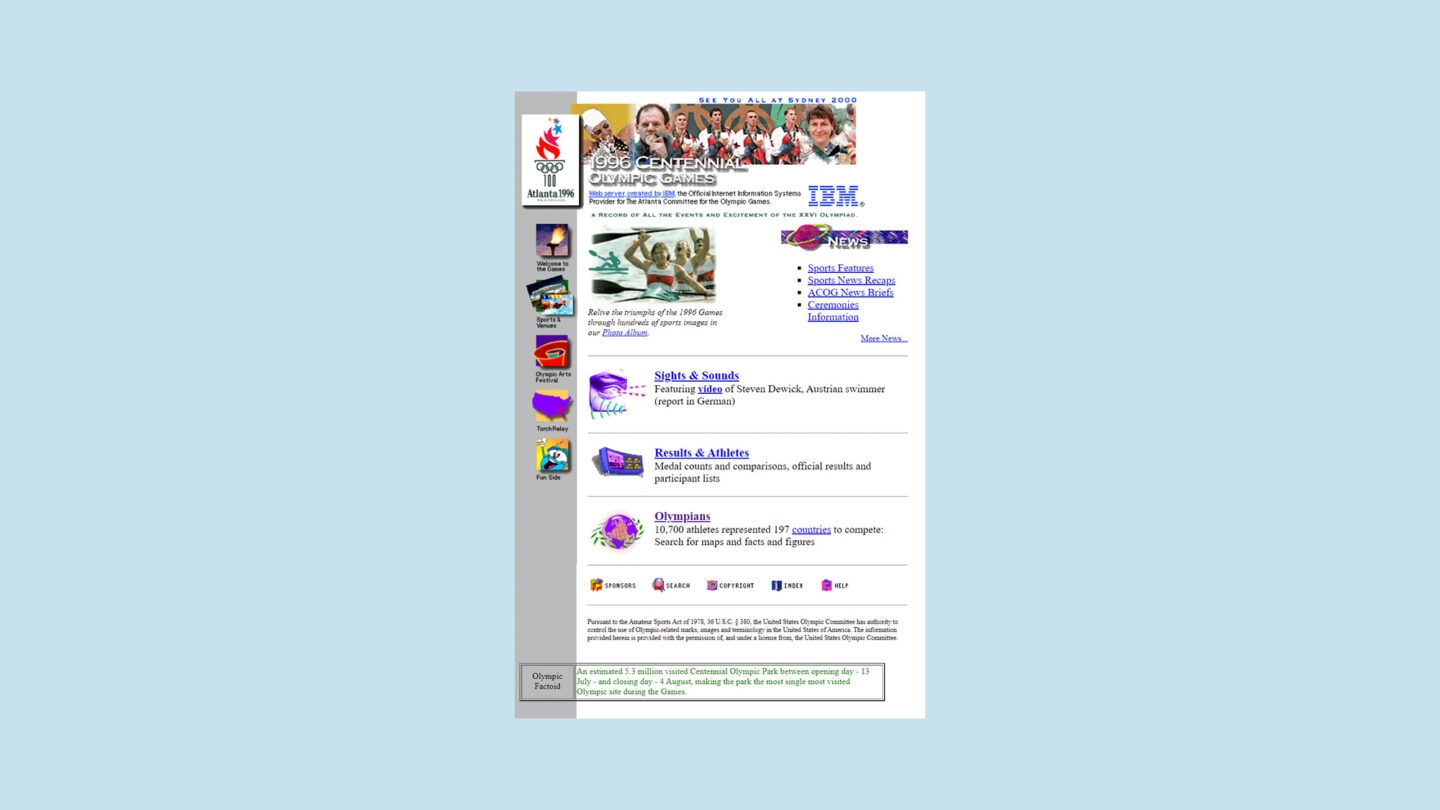

By the 1990s, IBM had held a multi-decade corporate relationship with the Olympic Games. The tech giant established their relationship for the 1960 Winter Games in Squaw Valley, California, when their job focused solely on providing hardware to the organizing committee. As the tech landscape changed rapidly in the late 1980s to early 1990s, IBM sought to expand their role in the Games. They hoped to demonstrate the company’s adeptness at larger-scale computing services as well as their ability to make a foothold in the new field: the internet. When Netscape web browser launched in October 1994, the idea of personal and commercial use of the internet caught on quickly. IBM convinced IOC and ACOG staff to create the first official website for an Olympic Games.

Interior of IBM Surf Shack in Olympic Village | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, circa 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

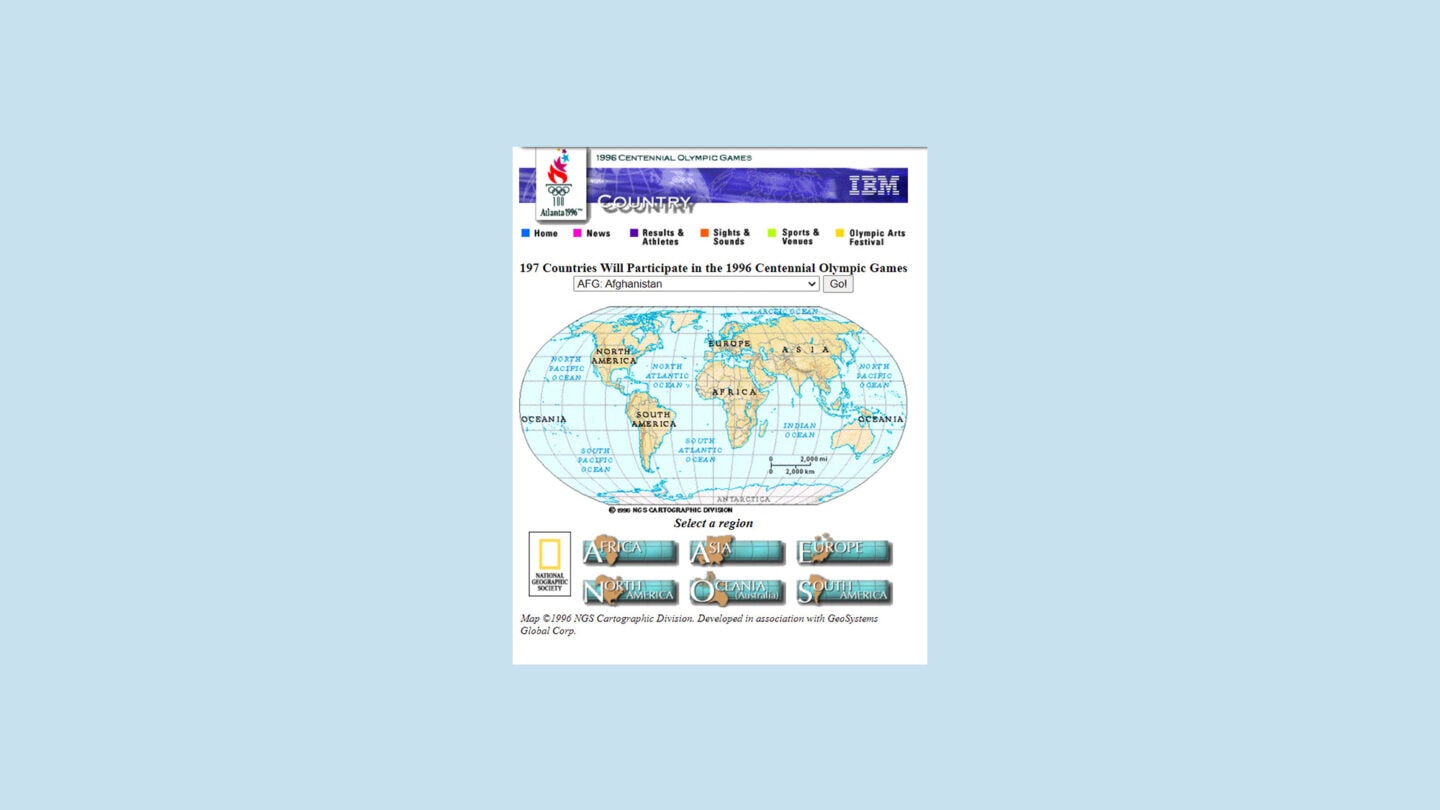

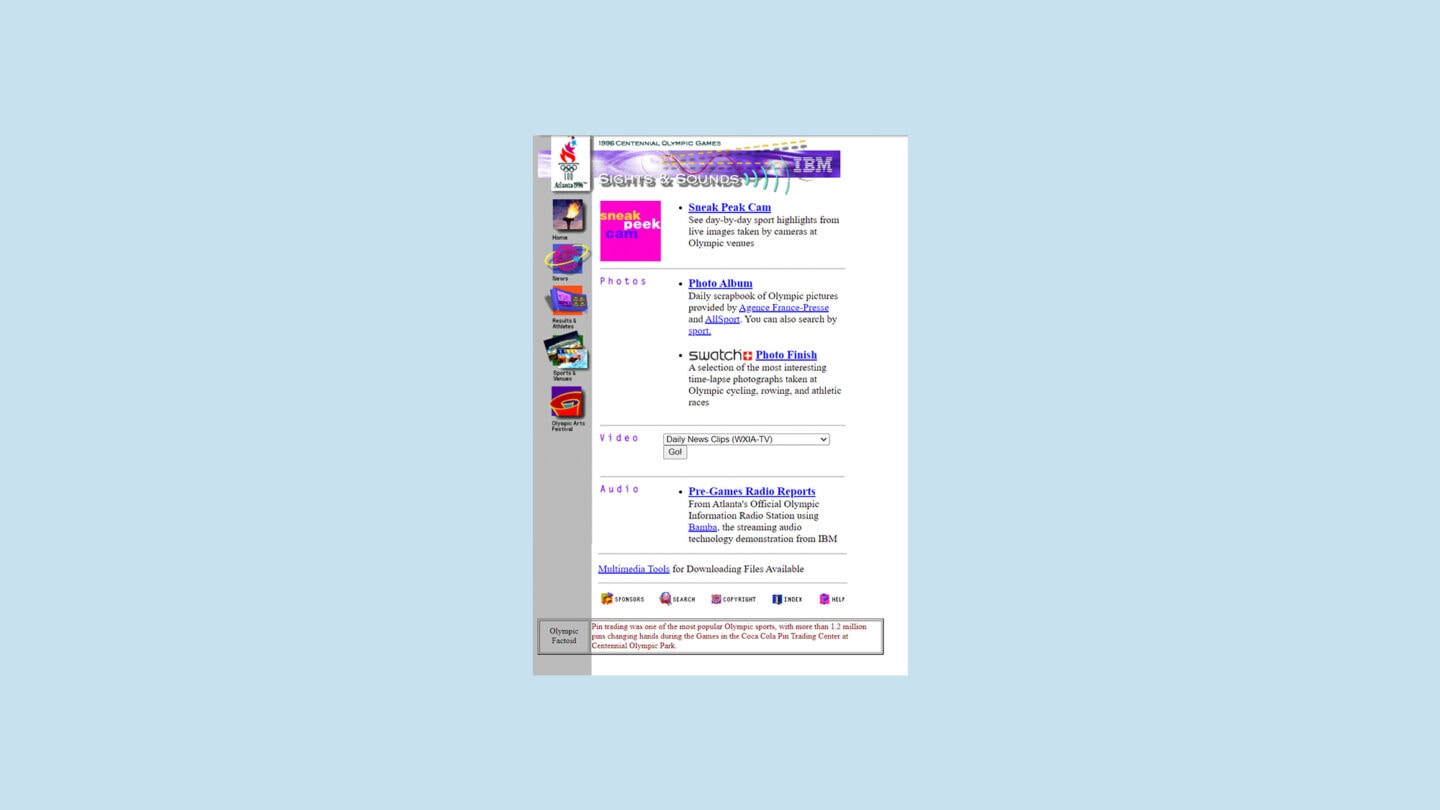

The site went live in April 1995. It was planned to be a hub of information for all things related to the Games. The website quickly attracted traffic and attention, and joined a community of sites and pages dedicated to Olympic-related content as the summer of 1996 approached. It averaged about 10,000 hits per week in advance of the Games with significantly greater activity during the two weeks of the Games. During the Games, staff uploaded between 300-400 photographs of events to the site each day. It included an interactive map of all participating nations, narratives of Olympic history, and a detailed day-to-day schedule. When tickets were released in the months before the Games, organizers even arranged to sell tickets online, joining the early e-commerce surge of the mid-1990s. The site was kept current with results reporting from sporting events.

There was even a section devoted entirely to the athletes. Each Olympian could set up their own personal homepage and send and receive “FanMail” through an email account hosted by IBM. The virtual Olympics craze spread. Fans and media outlets launched websites in time for the Games or experimented with new web-based content to keep up with the excitement of the event. Journalist Lisa Napoli posted on a corner of The New York Times’ website called “CyberTimes Olympic Coverage.” She talked about the new experience of keeping up with an event “virtually” and regularly checked in on the latest edits to athlete homepages and fan mail content.

IBM also built the first official Paralympic Games website, launching around the same time as its Olympic counterpart. These projects were a reach for the company, as the then-small internet division built what was possibly the largest website project yet attempted by its launch in 1995.

Instant Info and Instant Glitches

The website was just one component of IBM’s big stretch for the Games in Atlanta. Around the time of the 1994 Winter Games in Lillehammer, Norway, the company convinced the International Olympic Committee to let IBM provide all IT infrastructure for the Games. This meant the company typically in charge of just providing computing hardware would develop an “integrated solution” for all tracking and reporting needs of the Games as well.

We were part of a wave of innovative, experimental projects that were trying out all kinds of new Web applications.

IBM’s system would ensure that all various timing and scoring systems were networked together, so that results would get to Games officials, press, and published logs on the website in real time. The plan aimed to make technology the big news of the 1996 Games. IBM dubbed this one-stop-shop network “Info ’96.” The project even included public kiosks installed near Olympic venues that allowed visitors to access daily event schedules, transportation information, and athlete bios.

IBM Staff Members With Info ’96 Kiosk in ACOG Offices | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, 1995 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The project was groundbreaking for the IBM team and there were a lot of unknowns in what they were attempting. Would the website hold up to an unknown amount of traffic? Did they have enough computing power to support all the information transfers? As the Games commenced, the website experience received positive feedback and IBM’s networks successfully transferred results to scoreboards and judges across the venues. However, the data delivery system that communicated this information to members of the press worldwide stumbled. Glitches in the system resulted in delayed communications and misinformation sent to news outlets, which in turn resulted in bad press for IBM and the Games.

Fast-Paced Fields of Play

Like other Olympic Games, Atlanta was a stage for advancements and achievements of all kinds. The advent of the commercial internet captured much of the attention, but the summer of ’96 introduced innovations across the board. Georgia Tech’s partnership generated new traffic management technologies, solar power efficiency experiments, and athletic performance studies.

Telecommunications professionals laid 1700 miles of new fiber optic cable in the Olympic core during construction phases of venues and the Olympic Village.

Outside of Atlanta, companies tested new materials and equipment designs for sportswear, bicycles, and more.

ACOG Staff Members in the Ticket Office | Marilyn Suriani, photographer, Atlanta, 1995 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The history of technology and digital innovation can help bring to light the trial, error, effort, and resources it took to develop the digital infrastructure and technological capabilities we may take for granted today. Its face-paced evolution is always continuing. Limitations of hardware and infrastructure have often abutted imagined possibility of new media and technology, creating many failures on the way to breakthroughs. Technology has transformed the way we work, live, and engage with each other in so many ways. These stories often conjure feelings of nostalgia from those who remember older devices and processes, or deep unfamiliarity from younger individuals.

The Olympic Games continue to be a stage for these developments. The postponed 2020 Games in Tokyo have announced the goal of being “the most innovative in history.” Robot fleets will fill the Olympic core of the city, helping with wayfinding, heavy lifting, delivery, and other tasks. High speed city transit will help with congestion and transportation. And new 5G technologies aim to make the Games hit benchmarks for connectivity. New technologies are also advancing environmental goals and changing architecture. Who knows what will be next?

Learn more about the technology created surrounding the Atlanta Olympic and Paralympic games at our newest exhibition, Atlanta ‘96: Shaping an Olympic and Paralympic City.

Additional. Resources.

- Atlanta Magazine | What is it? An oral history of Izzy, the mascot marketing snafu of Olympic proportions | Max Blau, June 23, 2016

- The Baltimore Sun | Access Puts Many on the Same Page Internet, Web Sites Provide Instant Info | Kevin Langbaum, July 18, 1996

- CERN | A Short History of the Web

- The Christian Science Monitor | Race to Get Information Out is Olympic Event | Kristen A. Conover, July 16, 1996

- Forbes | IBM, Olympics Part Ways After 40 Years | August 22, 2000

- Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine | Vol. 73, No. 1 1996

- International Olympic Committee | Tokyo 2020 Games Innovative Initiatives

- New York Times | CyberTimes Olympics Coverage | Lisa Napoli, July–August 1996

- New York Times | I.B.M. Seeks Its Footing After Atlanta Stumble | Peter H. Lewis, July 29, 1996

- Ohio State Press Books | CG Historical Timeline

- Popular Mechanics | In Atlanta in ’96, Low-Tech Internet Revolutionized the Olympic Games: Time Machine July 1996 | October 1, 2009

- Memories from the 1996 Atlanta Olympics | Irving Wladawsky-Berger, August 20, 2012

Major support of this exhibition has been generously provided by the James M. Cox Foundation, Marine and John A. Fentener van Vlissingen, Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, The Coca-Cola Company, Martha and Billy Payne, The UPS Foundation, Martie and Dennis Zakas, and The Rich Foundation.