Editor’s note: Atlanta History Center is uncovering and sharing the histories of the descendants of Forsyth County’s Black residents who were expelled in 1912. If you are a descendant of the 1912 Forsyth County displacement, contact us at forsyth1912@atlantahistorycenter.com.

In 1912, more than 1,000 Black people fled racial violence in Forsyth County. White residents of the county had begun terrorizing Black Forsythians, lynching one Black man and convicting two others, after the sexual assault and murder of local white resident Mae Crow. When Black Forsythians were forced out, they left behind their homes, property, churches, schools, and cemeteries. They also left the interconnected community they built as they dispersed across Georgia and the United States.

Newspapers documented the lynching and banishment of Black residents from Forsyth County, but the questions remain: Who were they, and where did they go when they left? As part of an ongoing project in the Digital Storytelling department at Atlanta History Center into the history of the 1912 lynching of Rob Edwards and subsequent expulsion of African Americans in Forsyth County, the department has conducted research into the locations of these residents before and after the 1912 expulsion using census records, marriage licenses, death certificates, draft registrations, and more.

Map of Black population across all 12 districts of Forsyth County in 1910. Atlanta History Center

Black Population of Forsyth County in 1912

| District | Population | Households Owning | Households Renting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barker | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Bells | 92 | 2 | 13 | |

| Big Creek | 208 | 11 | 26 | |

| Chattahoochee | 63 | 2 | 8 | |

| Chestatee | 11 | 1 | 2 | |

| Coal Mountain | 61 | 0 | 10 | |

| Cumming | 354 | 17 | 55 | |

| Hightower | 62 | 1 | 12 | |

| New Bridge | 37 | 1 | 6 | |

| Rolands | 66 | 2 | 12 | |

| Settledown | 12 | 0 | 1 | |

| Vickery Creek | 149 | 3 | 24 | |

| 1,117 Black Residents | 40 Households Owned | 170 Households Rented |

Table of Black population across al 12 districs of Forsyth County in 1910. Atlanta History Center

Forsyth County in 1910

In 1910, the United States Census Bureau abstract for Georgia reported 11,940 people living in Forsyth County. Of those 11,940, the bureau reported 10,842 white and 1,098 Black residents. However, the 1910 Census enumerates the Black population of the county as comprising 667 Black and 450 Mulatto residents, or 1,117 people, making up 9% of the population of Forsyth. Black Forsythians lived across the county, but most lived in or near the city of Cumming and the southwest part of Forsyth, which was closest to the Georgia state capital in Atlanta.

Occupations

The occupations of residents of Forsyth were consistent with other rural populations in the state. Like many rural populations, farming was the primary occupation in the county in white and Black households. Thus, most Black residents, primarily Black men, farmed in some capacity. They were sharecroppers, laborers, or farm owners. Black women typically worked on their family’s farm, as domestic servants, or kept house. In addition to farming, some Black residents held occupations supporting the greater Black community, including teaching, blacksmithing, carpentry, and clergy.

Property

About a quarter of Black households in Forsyth County owned property. Of the 210 Black households listed on the 1910 census, 40 owned properties and 170 rented. The 40 Black landowners in Forsyth owned hundreds of acres of land. The 23.5% of Black households in Forsyth who owned land were on par with the national average of 23.7% of Black households who owned land across the United States in 1910. Statewide, the quarter of Black households that owned property in Forsyth County was statistically higher than the Georgia average for Black household ownership which was 15.3%.

When white residents in Forsyth County began forcing Black residents out of the county in 1912, some Black landowners sold their land early at a loss, but most had to abandon their properties. They were never able to return and claim their land because white residents barred Black people from entering or living in the county through threats, intimidation, and violence. White residents also took over the land as their own once it was legally declared abandoned. As Forsyth County transitioned from a rural to a suburban area, white families sold this land to business entities and the local government to create neighborhoods, shopping centers, and schools. Today, the average selling price for a property in Forsyth County is more than $900,000.

Identity

In early census recordings, census takers identified the Black population of Forsyth as either “Black” or “Mulatto.” Mulatto is an outdated and offensive term used in the census to categorize mixed-race individuals in the United States with both Black and white ancestry. This term was used in multiple census reports to describe Black individuals who identified as, or appeared to be, mixed race. In 1910, census takers listed 658 Black residents in Forsyth County as Black and 440 as Mulatto. The mixed-race population made up 40% of the Black population in Forsyth. Nationally, census takers reported 23.4% of the Black population as mixed-race in 1910, making Forsyth County’s reported mixed-race residents almost double the national average.

Many prominent Black families in Forsyth shared last names with prominent white families such as Bagley, Strickland, or Julian. The white Strickland families in Forsyth County owned the largest enslaved population in the county. Bagleys and Julians also enslaved people. Because census records of enslaved populations did not list names of enslaved people but rather whom they were enslaved by, there is no way to know how many Black families who shared last names with white families were formerly enslaved by or biologically related to them. Given that the sexual abuse of enslaved women by white enslavers was common and many of the older generations of these Black families in 1910 were formerly enslaved, it is not farfetched to deduce that some former enslavers and their descendants expelled Black families they formerly enslaved or to whom they were biologically related.

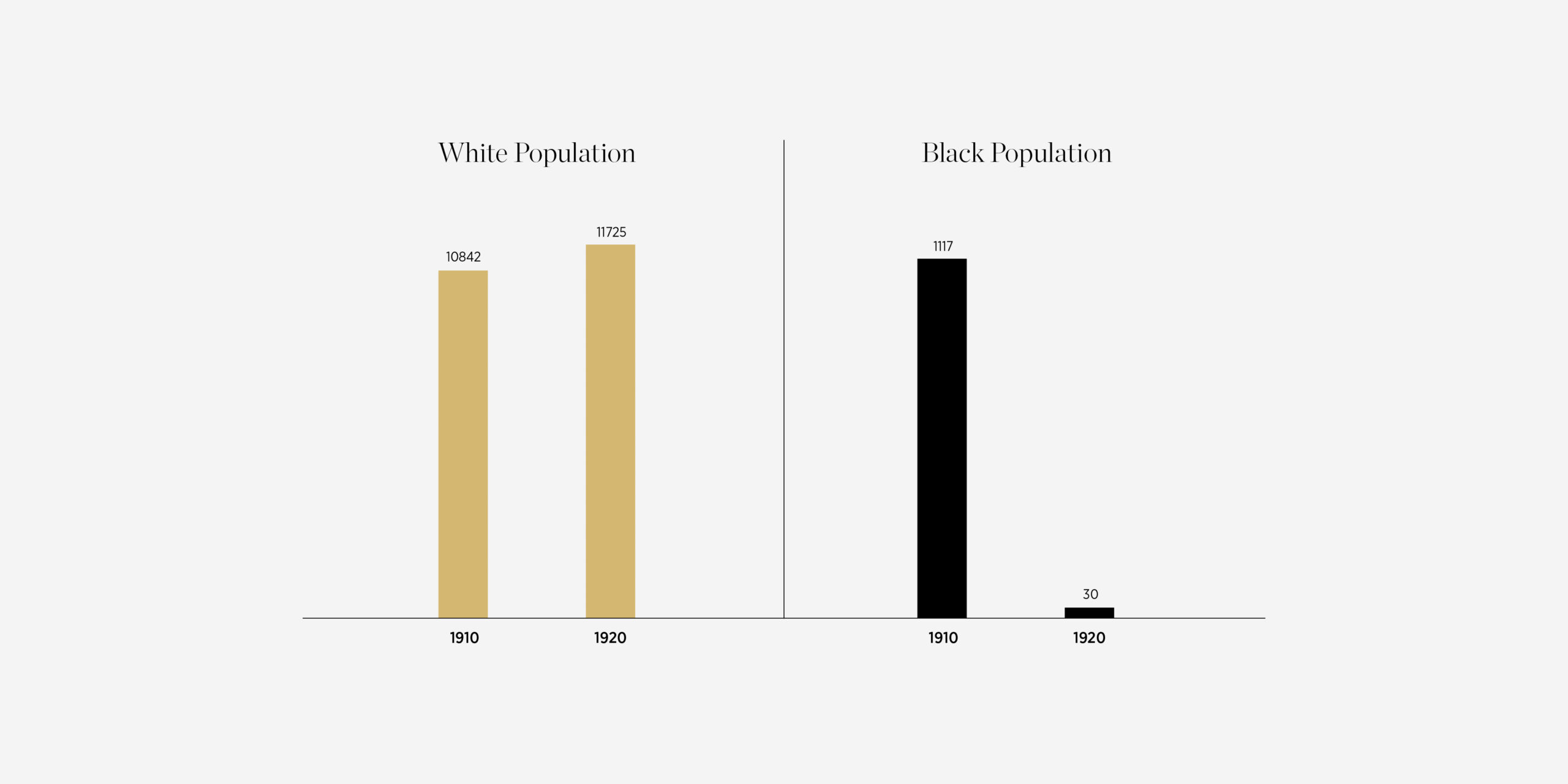

Changes in the Black and white population of Forsyth County in 1910 and 1920. Atlanta History Center

Forsyth County from 1920 to 1980

In 1920, the U.S. Census Bureau reported 11,755 people living in Forsyth County. Of those 11,755, the bureau reported 11,725 white residents and 30 Black residents. While the total population decreased by 1.6%, the white population increased by 8.1% and the Black population decreased by 97.3%. All the reported Black residents in the 1920 Forsyth County census lived in Big Creek, the southernmost district of Forsyth County, which today borders Fulton County.

While there are Black residents reported in the 1930, 1940, and 1950 censuses as living in Forsyth County, it is much more likely these residents lived in a town that bordered the county called Sheltonville and, later, Shakerag. This area is current-day Johns Creek in Fulton County. Sheltonville/Shakerag is identified on maps at different times as being in Forsyth, Milton, and Fulton counties. This area sat on the border between Forsyth and current-day Fulton County on McGinnis Ferry Road. Will Strickland, his wife Carrie, and their children are examples of a Black family who lived in Big Creek in 1910 and 1920. However, descendants of this family explained that their ancestors later fled to the Johns Creek area. Therefore, it is possible the Stricklands were able to remain in Forsyth by living close to the border, but they could have also crossed just over the border to safety in Shakerag.

This is further supported by information provided in the 1930, 1940, and 1950 censuses. Lula Emerson, her husband John, and their children lived in Big Creek in 1910. In 1920, the Emersons were in the first district of Milton County, where Sheltonville/Shakerag was located. Milton County was later incorporated into Fulton County. In 1930, Lula Emerson was again in Milton County living on Sheltonville Road in the Milton first district. However, in 1940 and 1950, her location was listed as Forsyth County, still on Sheltonville Road.

One of Lula Emerson’s neighbors, Paul Rogers, followed the same pattern. In 1920, he lived in the Milton first district and was the son of Nathan Rogers, who had been forced to leave Forsyth County. Rogers was Emerson’s neighbor in 1930 on Sheltonville Road in Milton County and in 1940 in Forsyth County. They remained neighbors on Sheltonville Road. Lula Emerson’s obituary further reiterates that she was a Milton/Fulton County resident. So, while Black residents were listed on the census as being in Forsyth County from 1920 to 1950, they were all near the border in Sheltonville/Shakerag. This mistake on the part of the census takers fails to accurately reflect how white residents in Forsyth County maintained an all-white county. Newspapers documented racial violence against any Black person who entered Forsyth County.

As early as 1915, newspapers reported the ways in which Forsyth County maintained an all-white county. This included multiple instances of white residents chasing Black chauffeurs of prominent white men out of the county. As late as 1980, a relative of Mae Crow attempted to murder a Black man, Miguel Marcelli, after white residents saw him attending a work party at Lake Lanier. Descendants of expelled Black residents told of the warnings passed down from their ancestors never to enter the county. For many descendants, that fear still exists.

Former Black Residents Movement by Georgia County

| Georgia Counties | Number of Residents Located After 1912 | |

|---|---|---|

| Barrow | 5 | |

| Bartow | 28 | |

| Bibb | 1 | |

| Cherokee | 35 | |

| Clayton | 7 | |

| Cobb | 104 | |

| Dekalb | 32 | |

| Douglas | 28 | |

| Forsyth | 9 | |

| Franklin | 4 | |

| Fulton | 85 | |

| Gwinnett | 70 | |

| Hall | 46 | |

| Jackson | 17 | |

| Jeff Davis | 3 | |

| Milton | 39 | |

| Morgan | 6 | |

| Pickens | 3 | |

| Polk | 21 | |

| Walker | 4 | |

| Webster | 2 | |

| Total Found in Georgia Counties After 1912 | 549 |

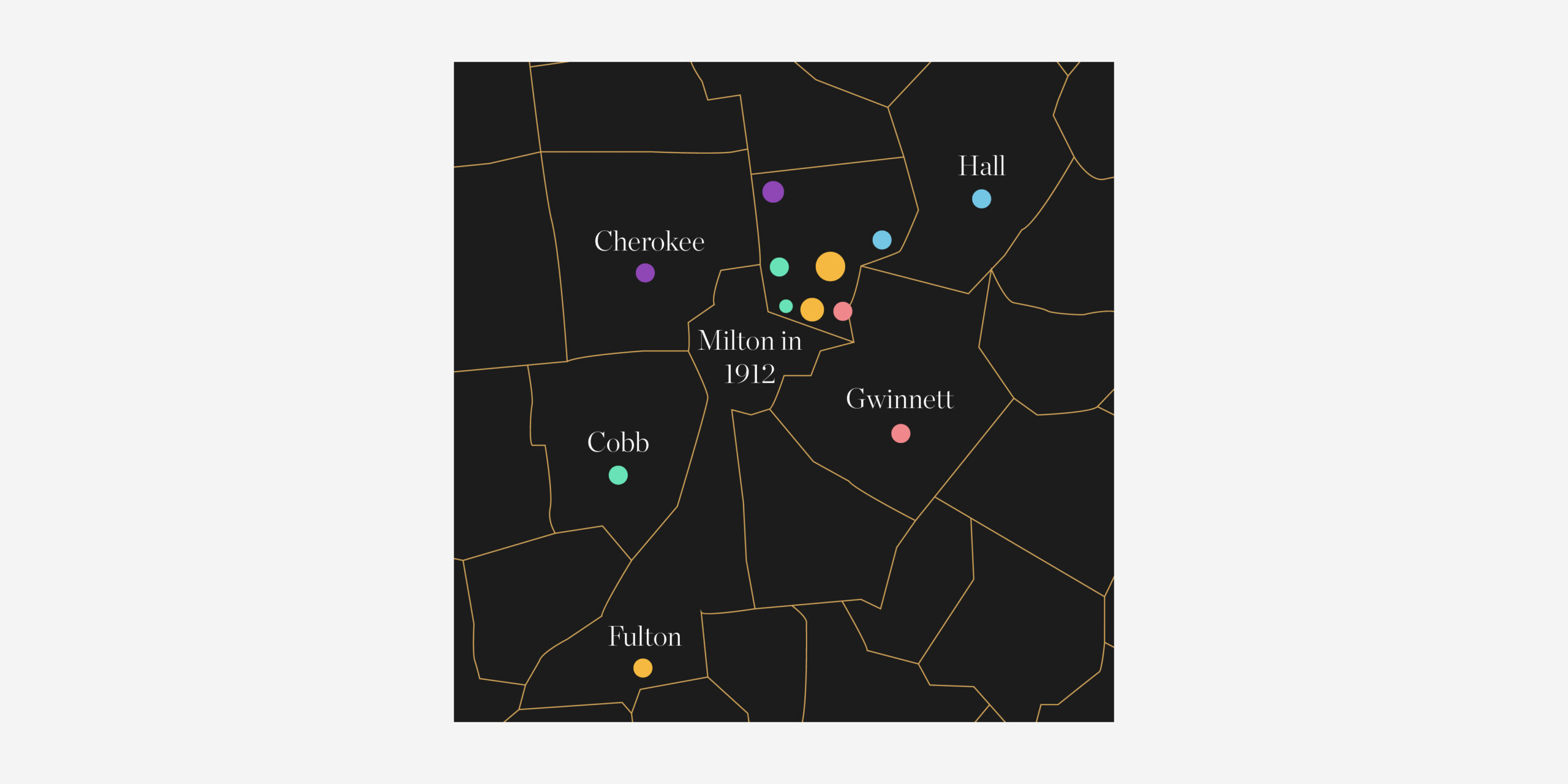

Data on the displacement of former Black Residents of Forsyth County by Georgia Counties. Atlanta History Center

The Movement of Black Residents

Of the 1,117 Black residents in the 1910 census, the Digital Storytelling Department has been able to compile data on the locations of 705 residents in the years after 1912. For most, the earliest information on their next location is the 1920 census, taken eight years after the expulsion. Other records, such as World War I draft registrations or death certificates, give earlier location information. Unfortunately, some former residents only have new locations in 1930 or even 1940, limiting our ability to know their earliest location post-1912.

While the locations of the 705 found residents give us essential information on Black residents of Forsyth County after 1912, there are still 412 individuals unaccounted for, leaving room for more exploration into their whereabouts. The 705 we can account for spread across 21 Georgia counties and nine states. Of the 705, there were 41 who were deceased in the years following the expulsion. Of the remaining 664, 549 fled to various Georgia counties.

Oral histories passed down to descendants explain how their ancestors fled Forsyth County, taking only what they could carry or put on wagons. Many of the Black people who left Forsyth County in the face of racial violence seem to have remained where they first fled. Milton, Gwinnett, Cherokee, and Hall counties bordered Forsyth and were some of the most common places to which they fled. Most settled in Cobb and Fulton counties, which had higher populations and more job opportunities.

Further data also reflects how the starting locations of Black residents impacted where they fled. For example, those on the county’s west side were more likely to flee towards Cobb County, while those in the south were more likely to move to Gwinnett, Milton, and Fulton County. In the north, Cherokee County and the state of Tennessee were likely destinations, while those on the east side fled to Hall and Gwinnett County. This data provides a broader picture of the terror experienced by Black residents fleeing to the nearest border.

Map showing where most Black residents fled to by district. Atlanta History Center

Former Black Residents Movement by State

| State | Number of Residents Located After 1912 | |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 5 | |

| Indiana | 9 | |

| Kentucky | 2 | |

| Maryland | 1 | |

| Michigan | 14 | |

| North Carolina | 1 | |

| Ohio | 9 | |

| Tennessee | 64 | |

| Total Found in Other State After 1912 | 105 |

Data on the displacement of former Black Residents of Forsyth County by state. Atlanta History Center

As residents fled and settled elsewhere, characteristics of the population changed over time. While most residents were still engaged in farming, especially in Georgia, those who moved out of state were more likely to take on industrial or service jobs. Additionally, many households consolidated into multigenerational and multifamily households. For example, relatives living in separate households in 1910 were found with parents, grandparents, or siblings later. Families struggled to bounce back economically after losing their homes, possessions, and occupations when they fled.

Changes in economic status are further reflected in changes to property status. Out of the 40 households that owned land in 1910, we found the later whereabouts of 32 of these households. Only one-third of former households which owned property in 1910 still owned property after 1912. Three of these former property owners were deceased by 1920, and other members of the household owned land in 1920. While some households continued to own property, two-thirds of 1910 property owners rented after white residents expelled them from the county.

Former Black residents did not just stay in Georgia; 105 moved to other states. Knoxville, Tennessee, was the most common destination, but other residents who moved to Indianapolis, Detroit, and Cleveland show how some former residents were part of the Great Migration.

Data on the locations and characteristics of the former Black population of Forsyth County gives us insight into where they went and ways in which their lives were forever altered by racial violence that forced them from their homes and community.