Cover of the French magazine, Le Petit Journal, October 7, 1906, depicting a drawing, titled “Massacre of Negroes at Atlanta.” Atlanta History Photo VIS 170.1374.001, graph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

On Saturday, September 22, 1906, thousands of angry whites gathered at the corner of Pryor and Decatur Streets in downtown Atlanta. Fueled by sensationalized news reports of Black men brutalizing white women, many who gathered there sought to violently attack anyone who was Black.

Mayor James G. Woodward and other city officials unsuccessfully tried to calm the group. Woodward told the crowd, “For God’s sake, men, go to your homes quietly and leave this matter in the hands of the law —I promise you that every Negro shall receive justice and the guilty shall not escape.”

Despite Woodward’s pleas for order, the violent swarm of whites hunted and killed Atlanta’s Black residents into the night on Decatur Street, Pryor Street, Central Avenue, and the central business district, attacking hundreds of Black Atlantans and their businesses.

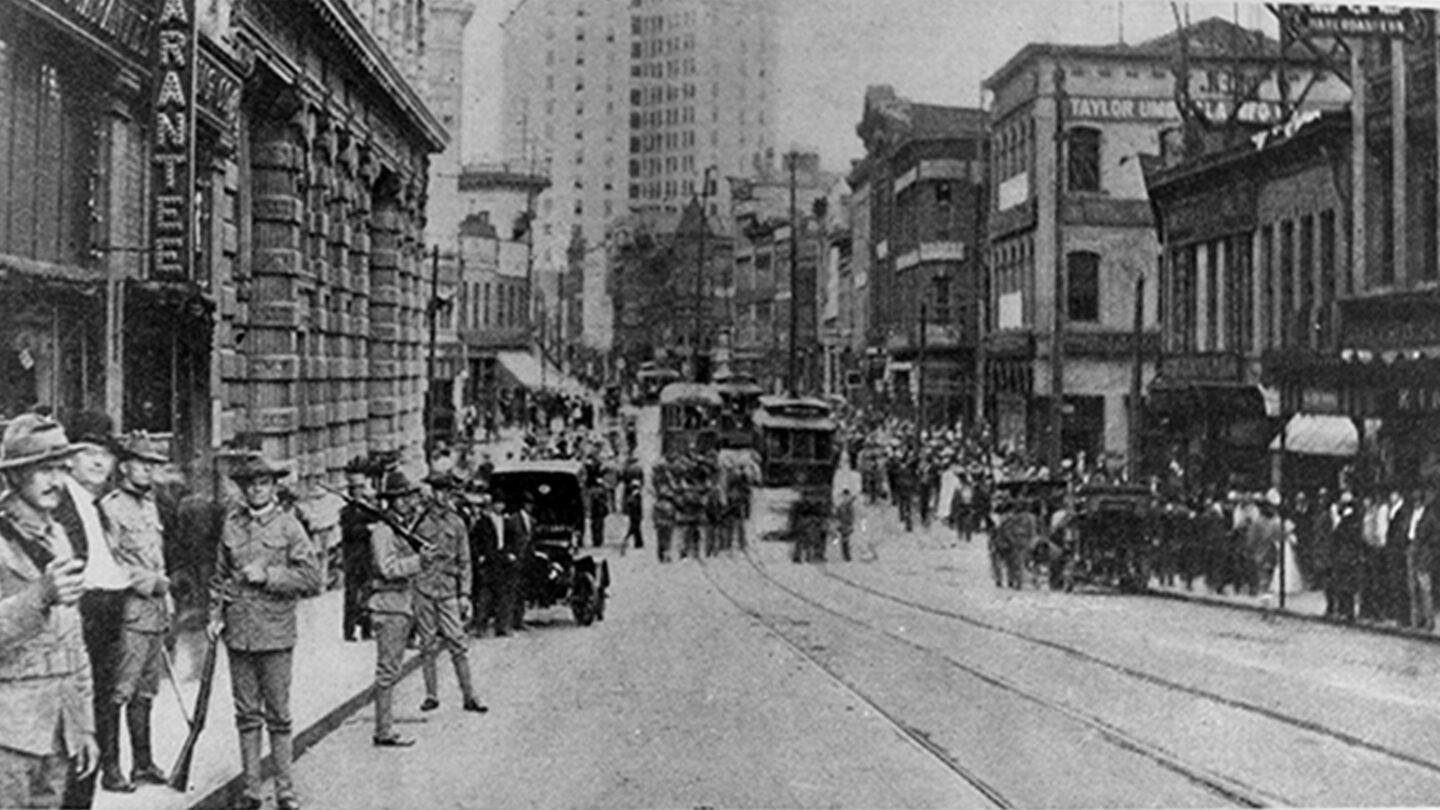

According to the Atlanta Constitution, police arrested about 70 white men and jailed them without bond on the first night of the massacre. By Monday, downtown Atlanta was under martial law.

Nevertheless, the violence continued as whites planned to attack the residents of Brownsville, a Black community south of Atlanta with about 1,500 residents.

Members of the Brownsville community gathered to prepare and fight back when they heard that a violent mob was headed their way. City of Atlanta officials were concerned about a counterattack, prodding Governor Joseph Meriwether Terrell to order the state militia to disarm Brownsville residents. While disarming the Brownsville residents, officials arrested 257 Black men and killed two. Throughout the massacre, Black residents defended their neighborhoods in Brownsville and Atlanta. There is still much we will never know about the events that took place during the massacre. At least 25 Black Atlantans were murdered, hundreds of Black residents were wounded, and many Black businesses and homes were burned or destroyed.

Georgia State militia on Peachtree Street just south of Five Points in the aftermath of the 1906 Race Massacre. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, VIS 170.2048.001, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Words hold significance for archivists who seek to describe the past in an unbiased and precise way. When conducting historical research, archivists must consider their own biases and pay close attention to the words they use. They must avoid taking one point of view as fact and neglecting other perspectives. As stewards of historical records, archivists try to accurately describe collections from diverse sources and perspectives, leaving it to the researcher to form conclusions about the materials.

Researchers often ask why the words used to describe the past change. While the basic facts of history remain constant, how we understand an account of the past can change as we are exposed to more perspectives and apply new knowledge. Language is fluid.

Ann Hill-Bond, a journalist and preservationist, first brought attention to the terminology used widely to describe the 1906 Race “Riot” as inaccurate. She is a part of a movement to rename the event a “massacre” and is a leading member of the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition. With her assistance, U.S. Representative Nikema Williams of Georgia’s 5th Congressional District introduced a resolution commemorating the Atlanta Race Massacre on the 116th anniversary in September 2022.

From the Oxford English Dictionary:

- Massacre (noun): an indiscriminate and brutal slaughter of people.

- Riot (noun): a violent disturbance of the peace by a crowd.

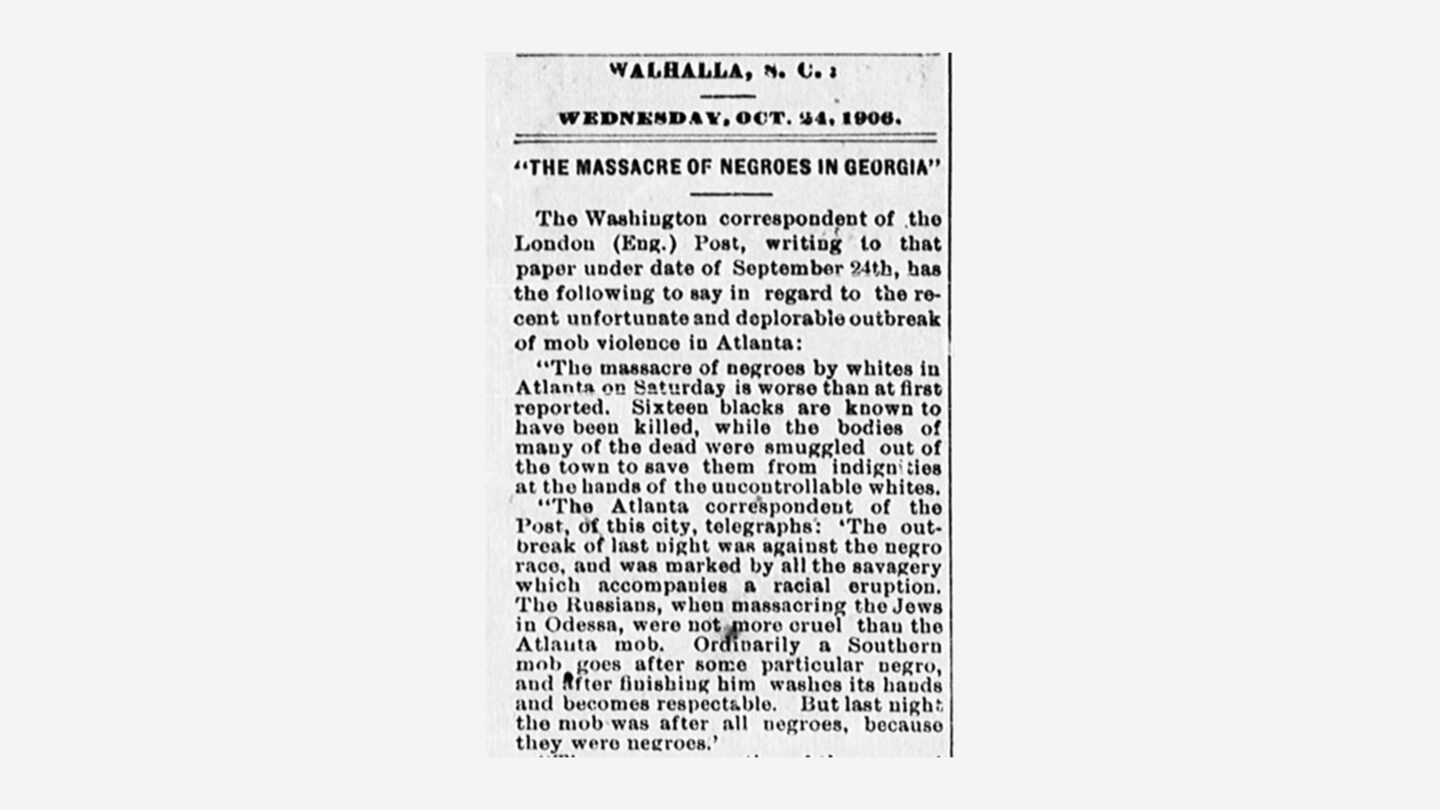

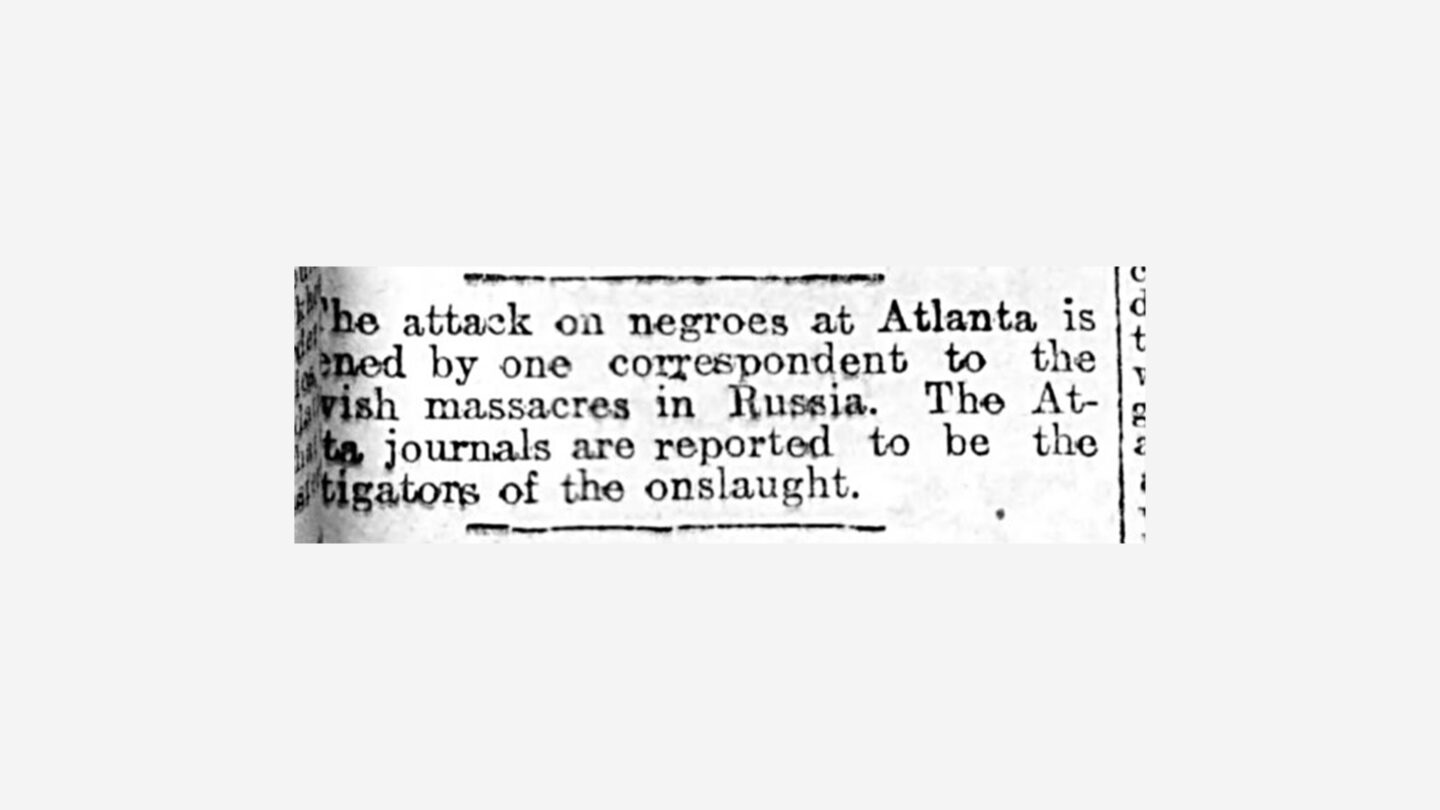

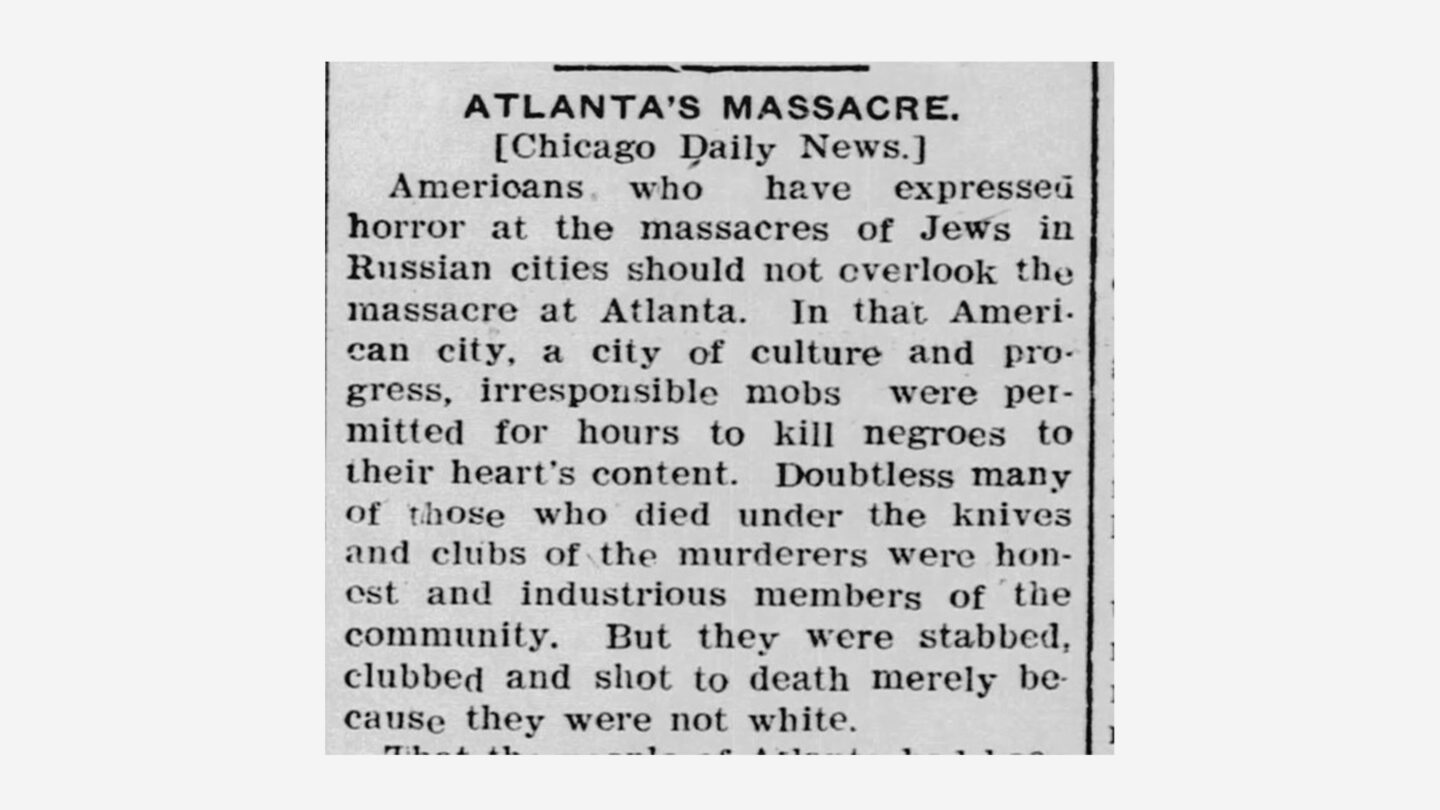

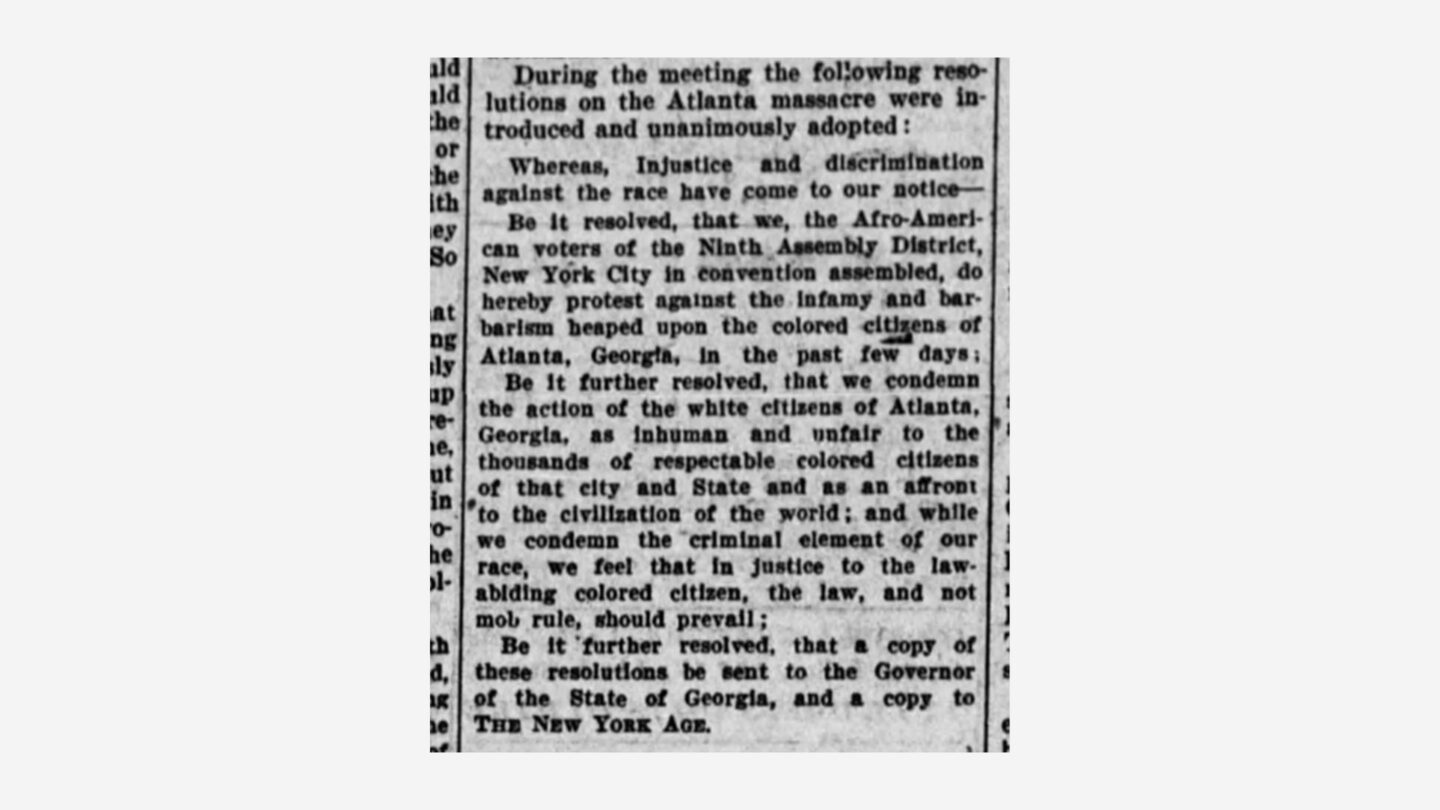

For 116 years the event was remembered as a “riot” in Atlanta history and begs the question: How many other massacres are hiding under the term riot? While researching the use of the word massacre versus the word riot, it became clear that worldwide, newspapers reported this event as a massacre in 1906.

However, Atlanta newspapers coined the event as a “riot.” The reasons for this are unknown, but one can surmise it was to control the narrative and image of the city.

The Atlanta City Council minutes that cover this event continue this narrative, which is not surprising as many city officials, including Mayor Woodward, had affiliations with Atlanta newspapers. The city council later describes the description of the massacre in the New York magazine World’s Work as “vile slander:”

“And Whereas, said magazine is published in New York and circulated through the South and the entire country and carries in its columns this vile slander upon our City and this Body. Resolved, by the Mayor and General Council, that we will not allow such articles to go unchallenged, and we denounce the same as false, slanderous and libelous upon our people and our City; that the word “thug” is a new word from this City, that it has never been applied to any class of our citizens before, and we deny that the streets of our City are ever thronged with a crowd of thugs, and we deny that a considerable part of Atlanta is made up of “adventurous riff-raff” that the mining towns of the west used to absorb. While there may be many rough people in our community, they are in a woeful minority.”—November 6, 1906, City Council Minutes and Index, Volume 21, 1906 April –1909 February 15

In response to this discovery, Kenan Research Center staff began to redescribe the collections associated with the event, both primary and secondary. In doing so, the lack of an accurate Library of Congress subject heading became apparent (subject headings are controlled vocabulary terms that are shared across institutions, similar to social media hashtags). A “Race Riot” heading exists, but a “Race Massacre” heading does not. After reaching out, we quickly learned there is a dedicated group of people doing reparative work with Library of Congress headings, the African American Subject Funnel Project.

The Library of Congress committee discussed our suggestions in depth and the addition of a term to accurately describe this event and others is in the works. While adding a heading takes a great amount of time and effort, the conversation has begun. The work does not end with adding a subject heading. How will we address vocabulary in catalog descriptions? How do we serve the individuals who may not be aware of the word change? The issue with the fluidity of words is the aftermath of the change. For example, if a patron were to come in and search “Race Riot,” we would still want the collections that relate to the massacre to populate; however, it would read “massacre.” This would more accurately describe the event.

Although these are just words and subject headings and they change nothing about the horrific event that took place 116 years ago, they shift the perspective. By describing accurately, we can educate and learn. Never underestimate the weight of a word. If you are interested in the collections at Kenan Research Center has related to this event or any other collections, please contact reference@atlantahistorycenter.com.

Additional Resources:

- Rebecca Burns, Rage in the Gate City: The Story of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, revised edition. Athens: University of Georgia Press. 2009.

- Race Massacres —Georgia – Atlanta, 1906 (Subject file), Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center