U-505 image. Gift of Donna B. Fullilove, 2023, Atlanta History Center

The potential donor’s email began, “I have my father’s WWII memory log from the USS Guadalcanal,” and that’s all I needed to see before I picked up the phone to call the donor to tell her yes, we would be very interested in acquiring her father’s memory log for our collection.

She knew the USS Guadalcanal’s story, of course, but most people do not. I didn’t know it when I first visited the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry in 2006 at the urging of a friend.

There, carefully preserved and housed four stories beneath street level, I got my first look at the villain of one of the most unusual stories of World War II: The U-505. She was the first enemy warship captured by a U.S. vessel on the high seas since the War of 1812, and she looked every bit as deadly as she did 80 years ago when a task force led by the USS Guadalcanal stopped her off the coast of Western Sahara on June 4, 1944.

Admiral Daniel V. Gallery, then Captain of the Guadalcanal, explained how the capture unfolded in his book, “Twenty Million Tons Under the Sea: The Daring Capture of the U-505.” Despite the German crew’s best efforts to scuttle the sub, Gallery’s men were able to board the ship, stop it from sinking, and tow it more than 2,500 miles through active U-boat-infested waters to Bermuda, where it gave Allied forces their first good look at a German submarine.

The German crew was rescued and spent the rest of the war in a prisoner-of-war camp in Louisiana. In an unusual violation of the Geneva Convention, U.S. officials never permitted them to contact their families, and they were presumed dead until they were repatriated to Germany in 1947. The entire operation was kept top secret.

German U-boats were a terrible threat to Allied forces in the Atlantic during World War II, sinking about 3,000 merchant and battle vessels, but the capture of the U-505 wasn’t just about removing the immediate threat the submarine posed to shipping.

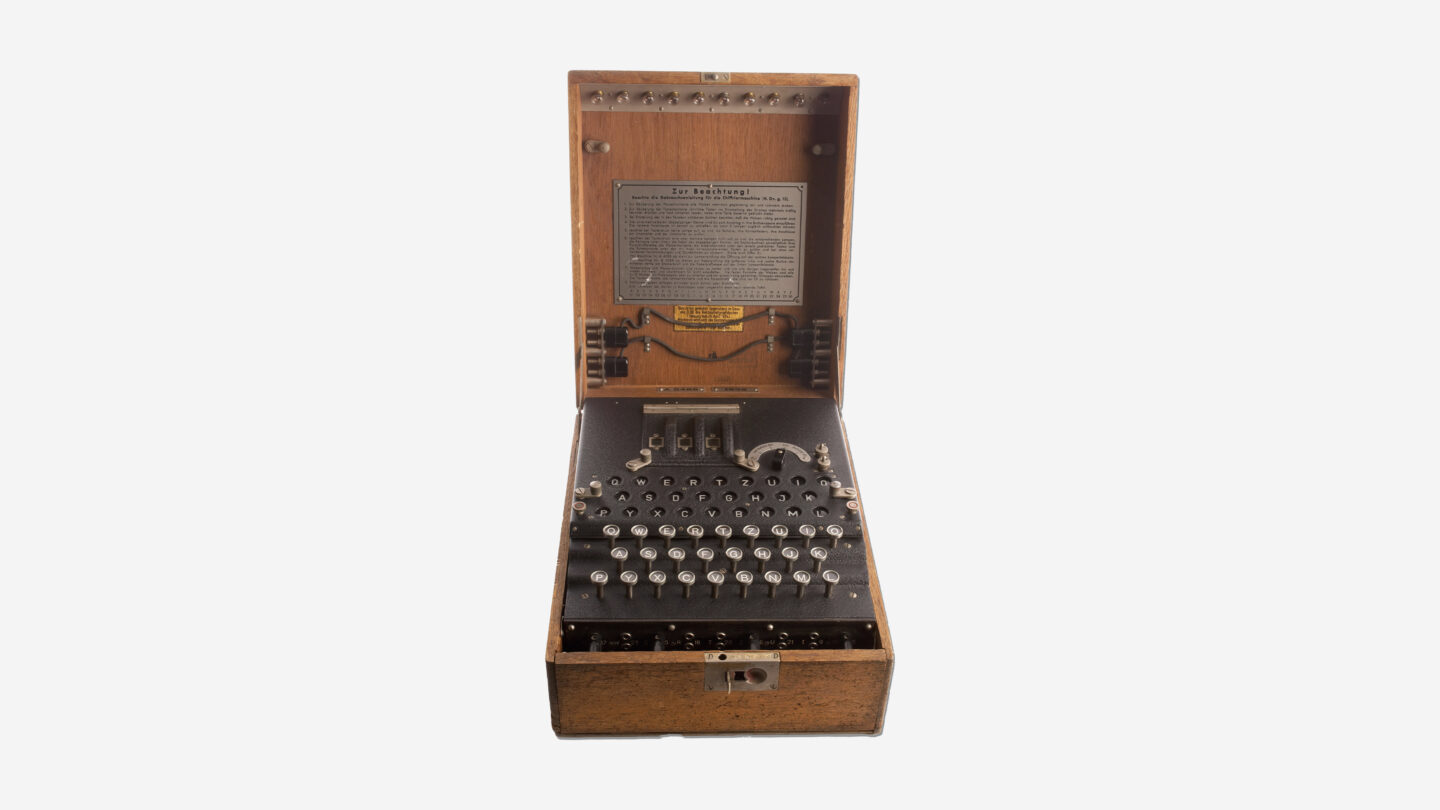

Enigma machine. Wikimedia Commons

About 900 pounds of codebooks and documents and two Enigma code machines were taken from her, the most extensive intelligence haul seized during the Battle of the Atlantic. It’s estimated that her capture saved the U.S. Navy’s code-breaking teams about 13,000 computer hours and significantly aided their work for the remainder of the war.

Our donor’s father, Raymond H. Bastian, was not on the Guadalcanal when the capture occurred. He joined the ship’s crew shortly afterward. Sadly, he died in 2000, so we were never able to interview him for our Veterans History Project.

But Janice Benario, a retired professor of modern and classical languages at Georgia State University, sat down with us for an interview on October 6, 2004, and explained the role she played in those code-breaking efforts that helped win the war.

Benario was a senior at Goucher College in Fall 1942 when her English professor encouraged her to enroll in a secret cryptology course offered there by the Navy. The class met on Friday afternoons in a locked room on the top floor of one of the classroom buildings. When she graduated in Spring 1943, she was inducted into the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and commissioned as a Navy ensign in Summer 1943.

“One girl from Radcliffe, two others from Goucher, and I were assigned to the most highly classified office in the Naval Communications Annex,” she said. “That was the office reading the Enigma messages from the German Admiral Karl Dönitz to his U-boats. The four of us were cleared to handle top-secret ‘Ultra’ material. That’s something no one else knew anything about, and we certainly couldn’t tell anything about it. In fact, on that first day, we were told that to talk would be considered treason in wartime. You know the punishment for treason. And so, nobody talked.”

Janice M. Benario served in the United States Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) as a cryptographer in Washington, D.C. during World War II. In this clip from her October 6, 2004, interview, she remembers the role the Enigma machines played in preparing for the Allied invasion of Europe and how she learned about D-Day.

Benario explained that “Ultra” and the atomic bomb were the two greatest secrets of World War II. Dönitz, commander-in-chief of the German Navy, communicated with his U-boats and controlled their maneuvers through the Enigma code machine, which the Germans considered impenetrable. The top-secret operation by the British, and later the Americans, to attempt to unlock the technology of that machine was code-named “Ultra.”

She explained that the German messages were decoded on a machine in another office. The secretarial staff printed the messages on long strips of yellow paper, which were then sent to the translators. Once translated into English, they were reviewed by a senior watch officer before being sent to her team.

“There was a big wall map of the Atlantic, the United States, and Europe,” said Benario. “We kept pins for each submarine we knew about and often received position reports, so we would move those pins to where they were. We kept track of the convoys; we had little pins with flags on them for convoys. Another important thing we did each morning, on the mid-watch around 7:30 a.m., we prepared an envelope with all of the messages, the translations from the day, the neutral shipping report, and a submarine U-boat report written by the research people with big letters across the top, ‘Top Secret Ultra.’”

“We put this in an envelope. It was signed over to an armed courier who appeared every morning at the Naval Communications Annex,” Benario said. “He put it in his locked bag, went out to his car, and carried it downtown to the main Navy department, where this envelope was taken immediately to the American submarine tracking room, which was the intelligence unit of Admiral Ernest J. King. There were only four people who were allowed in there who got these messages. It was those people who made the decisions on whether a convoy needed to be rerouted or whether we could go out and search for a submarine and destroy it.”

Photo of Janice Benario. Gift of Janice M. Benario, 2004, Atlanta History Center

Benario recalled that rerouting a convoy or finding a U-boat using this decoded information wasn’t as simple as one might think. The Allies were determined to keep their decoding success a secret. For example, if a decoded message indicated the position of a U-boat, the Allies would send a plane to the location to make it appear that spotting the sub was a random coincidence.

Dönitz became suspicious several times during the war, but his staff insisted that the Enigma machine could not be broken.

Benario left the service in May 1946 and faithfully kept her war work secret for more than 40 years. In 1991, her husband purchased a book about the Enigma machine, and she was stunned to see a photograph in the book that included her and the entire team in their office. That was the first time it occurred to her that it might be permissible to share her story.

“Now, some 50-odd years later, I am able to tell the story of my activities as a WAVE officer from 1943 to 1945,” she said. “My parents never knew what I did. They died before I could tell them. My husband only learned after 20 years of marriage. My children were in high school before they knew.”

Submarine Crossing. Courtesy Maureen Keillor

How the U-505 made it from Bermuda to a museum in Chicago in 1954 is yet another incredible part of the story, but in the interest of space, I’ll just say that I’m confident it’s the only time in Chicago’s history that Lake Shore Drive has featured signs declaring “Drive Carefully: Submarine Crossing.”

We are grateful to Raymond Bastian’s daughter for her generous donation of his memory log so that we can bring at least part of the story to life. She recalled him saying that he asked the crew of the Guadalcanal about that day in June 1944 when the U-505 was captured. They wouldn’t say much, and their fellow sailors quickly silenced those willing to share. Captain Gallery made it clear that secrecy was paramount.

In a June 14, 1944, memo to the crew, he wrote, “I fully appreciate how nice it would be to be able to tell your friends about it when we get in, but you can depend on it that they will read all about it eventually in the history books that are printed from now on. … Keep your bowels open and your mouth shut.”

It might still be one of the best-kept secrets of World War II. But it certainly makes one of the best stories.