Early Influence

Discovery of the Mississippi by De Soto, William Henry Powell, 1855, Capitol Rotunda.

The first Hispanic people to arrive in Georgia were Spanish explorers, such as Hernando de Soto, who were looking for gold, silver, and other valuable resources. After they arrived in the late 1500s, the Spanish founded Catholic missions and established military posts along the Georgia coast. However, after the British began settling in Georgia in the late 1600s, Hispanic influence in Georgia waned.

The British colony of Georgia was founded as a buffer between the Spanish in Florida and Britain’s colony in South Carolina. In 1742, General James Oglethorpe defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh, ending Spanish threats against Georgia.

Though initially a slave-free colony, subsequent to the Spanish defeat, Georgia permitted enslavement after 1750. As a result, Georgia’s enslaved population grew from less than 500 to approximately 18,000 between 1751 and 1775.

From an Island to a City in a Forest

Newspaper announcement of the wedding of Raul and Anne Trujillo, 1964. “Weddings and Engagements Announced,” Atlanta Constitution, August 7, 1964, Page 29.

In the 1950s, spurred by the Cuban Revolution, some Cubans left Cuba for the United States. To avoid alerting the Cuban government of their intent to flee, many families went to the U.S. one at a time, sometimes sending children alone.

Some immigrants, such as Raul Trujillo, made their way to Atlanta. Trujillo left Havana in 1962 with the clothes on his back as his only possessions. He attended graduate school at Georgia Tech to become an architect. Trujillo married fellow Cuban Anne York in 1964 and settled in Metro Atlanta.

With an influx of Cuban immigrants, Cuban families, such as the Trujillos, were instrumental in creating a community and communal support organizations that mirrored their identity.

The Marielitos

Congressman John Lewis talks with 10-year-old Rachel Rodriguez outside Atlanta Federal Penitentiary during a vigil by the Coalition to Support Cuban Detainees on behalf of Atlanta’s Cuban detainees , October 1987. Diane Laakso, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives.

Beginning in April 1980, a mass migration of Cubans was organized by Cuban Americans with the consent of Cuban President Fidel Castro. Departing from Mariel Harbor in Cuba, as many as 125,000 refugees traveled to the United States during the “Mariel boatlift.”

When the U.S. government decided to deport Marielitos, who had run afoul of the law, rather than giving them legal status in the U.S., Marielitos imprisoned at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, revolted. They held hostages and demanded freedom. In the end, due to the advocacy of Representative John Lewis, who argued for compassion, humanity, and support, most prisoners were reunited with their families and never repatriated.

There’s Work in Georgia

Downtown Atlanta, 1986. Cotten Alston, Cotten Alston Photographs, VIS 247.004.012, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Throughout the 1980s, the word was being passed: “Hay trabajo en Georgia,” or “There’s work in Georgia.” These messages flowed through networks of immigrant workers.

There was indeed work in Georgia. For working-class single men in Latin American countries, temporary work in the U.S. was a logical way to make money. These positions were typically seasonal at first. Permanent positions arose in the 1980s when there was a boom in suburban construction in Atlanta, carpet weaving in Dalton, and poultry processing in Gainesville. Further south, producers needed workers to harvest peaches, peanuts, and Vidalia onions.

With such plentiful employment options, men working in these industries began to forge fruitful lives for themselves. For this reason, documented and undocumented Hispanic families followed and began arriving in Atlanta.

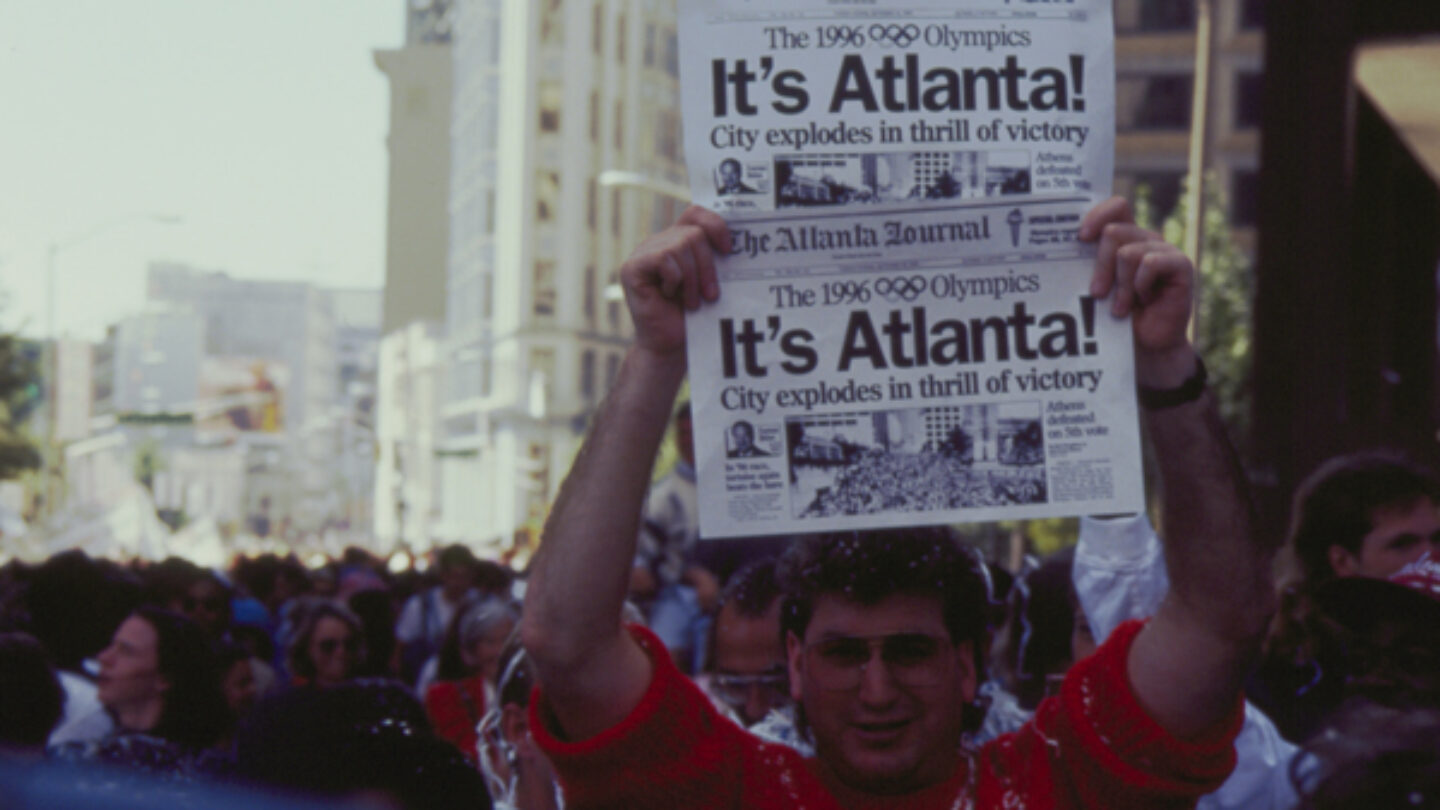

1996 Olympic Games

A man holds up copies of the Atlanta Journal announcing Atlanta’s selection to host the 1996 Olympic Games, September 1990. Cotten Alston, photographer, Cotten Alston Photographs, VIS 247.031.002, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

In the 1990s, Atlanta erupted with energy when it was selected as the site for the 1996 Olympic Games. While the city scrambled to get ready for the Games, there was a labor shortage. Many more immigrants from Mexico and Latin America came to fill the labor gap, helping ensure a successful 1996 Centennial Olympic Games.

Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young saw the Olympic Games as an opportunity to highlight Atlanta’s central role in the Civil Rights Movement and advance human rights. The influx of Hispanic immigrants, however, met opposition from those against immigration as their numbers increased and their presence continued beyond the 1996 Games.

Setting In

A Hispanic band performs on a float in a Christmas parade in downtown Atlanta in 1971. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, VIS 101.334.009, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Though many Hispanic people still have ties to their birth countries and own homes there, the Hispanic community has put down roots in Metro Atlanta and helped reshape the city’s culture, economy, and way of life.

According to the Pew Research Center, the Atlanta metro area now has one of the country’s largest concentrations of Latino people. The community is composed of residents from every nation in Latin America. Some speak Spanish, others Portuguese or French. More than half of the more than 1 million Hispanic residents in Georgia live in the Metro Atlanta counties of Cobb, Fulton, DeKalb, and Gwinnett, making up 14% of the area population.

Staying Connected

Mundo Hispanico, April 1982. Mundo Hispanico, Atlanta: Carola C. Reuben, publisher, Year 4, No. 3, 1982, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Spanish language publications, such as Mundo Hispanico and El Nuevo Georgia, are vital information sources for those who prefer to get their news in Spanish. Headquartered in Metro Atlanta, Mundo Hispanico is the largest Spanish-language weekly in the South. Other sources of information include El Nuevo Georgia, Telemundo Atlanta, and Univision 34.

Culture

A woman dances during a Day of the Dead celebration at Atlanta History Center Midtown. Staff photographer, Atlanta History Center

Atlanta’s vibrant and growing Hispanic community is represented at events, such as Festival Peachtree Latino, the largest multicultural event in the Southeast. The festival, which began in 2000, celebrates Latin-American culture. Other festivals include the Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration at Atlanta History Center, featuring traditional Mexican dancing, crafts, food, and entertainment. The festival results from a decades-long partnership with the Consulate General of Mexico and the Institute of Mexican Culture.

Community

Entrance to Plaza Fiesta. HispaFacts101, Wikimedia Commons

The Hispanic community has also established cultural centers, such as Plaza Fiesta. At the intersection of Clairmont Road and Buford Highway, Plaza Fiesta is a 350,000-square-foot Mexican flea market-style shopping center with retail and specialty stores, restaurants, healthcare services, and a fitness center. It is an important shopping destination for the Atlanta immigrant population.

Visible Work, Hidden Essential Workers

Maria Fajardo shows off produce that she is typically responsible for cultivating. Hector Amador, photographer, Amadorphoto, Latino Community Fund Georgia

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people rightly recognized first responders and medical professionals as heroes. However, other professionals, such as farm workers and domestic laborers, helped keep Atlantans nourished and safe during the pandemic. Often diminished as “unskilled workers,” domestic laborers and farm workers worked tirelessly to keep places clean and food on our tables.