Photograph from Lonesome Cowboys. Promotional photo from Andy Warhol’s comedy, Lonesome Cowboys. (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Georgia State University Library Exhibits)

In the summer of 1969, a spirit of rebellion reverberated from New York City and touched down in Atlanta.

Its impact here was little more than one month after a police raid at New York City gay bar, the Stonewall Inn, and the resistance that followed. The subsequent five days of protests jumpstarted the gay rights movement. By early August, police officers and protestors had stopped physically fighting. The streets had been cleaned and the Stonewall Inn reopened. People had settled back into their everyday lives. But the tide had permanently shifted as became clear when Gay Liberation grew rapidly in the coming years.

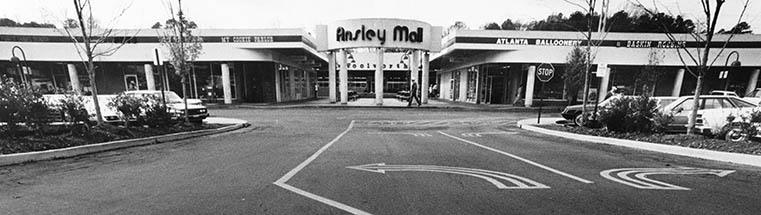

It’s likely that this spark of hope, self-identity, pride, and defiance had already rooted itself in the minds of roughly 70 people in Atlanta as they made their way to their seats for a film at Ansley Mall Mini-Cinema, unaware they were settling into the South’s very own Stonewall.

Front entrance of the Ansley Mall shopping center. (Georgia State University Library Exhibits)

On Aug. 5, 1969, the Atlanta Police Department entered a screening of Lonesome Cowboys, a homoerotic underground comedy directed by Andy Warhol. The Atlanta Constitution bluntly described the film as “not the kind of movie where you send the kids on a Saturday afternoon.” Fifteen minutes into the film, it abruptly stopped. The house lights in the theater came on and Atlanta police officers rushed into the aisles of the theater. It was a raid.

The police selected the theater to enforce obscenity laws in response to the film’s contents as well as to identify attendants. Many of the audience members—targeted for being “known homosexuals”—were harassed, photographed, and arrested.

“They had everybody get up and line up,” said Abby Drue, an LGBTQ activist who was present at the cinema during the raid. “We had popcorn in our mouths. I think I had a submarine sandwich I was in the middle of eating. That’s how absurd it was.”

The gay community had been harassed by police in Georgia many times before, but for police to raid a movie theater was regarded as a particularly powerful image of violation.

A few days after the raid, protesters at the local alternative newspaper, Great Speckled Bird, were confronted by police, sprayed with mace, and many arrested. That protest foreshadowed what was to come. The Stonewall riots and the Lonesome Cowboys raid motivated Atlanta’s Gay Liberation movement, leading many in the LGBTQ community to become more daring in their activism.

People participate in an Atlanta Pride event in 2002. The first Atlanta Pride took place in 1971. (Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Following the raid, activist members of Atlanta’s LGBTQ community met at the New Morning Café in Emory Village and formed the Georgia Gay Liberation Front. The group quickly got to work, registering LGBTQ people to vote, protesting anti-gay laws, and organizing the first Atlanta Pride event in 1971.

Although the City of Atlanta refused to grant GLF a permit for the Atlanta Pride event, 125 people still walked up the sidewalk along Peachtree Street—many wearing paper bags over their heads to avoid being identified—commencing a tradition fundamental to the fight for LGBTQ rights in Atlanta.

The raid at Ansley Mall represented the reason many in the LGBTQ community stayed hidden. Fearing discrimination and violence due to constant police harassment and the negative social stigma surrounding LGBTQ identity, they lived quiet lives consisting of private gatherings. They found each other through intuition and tried their best to be incognito as they made their way to gay-friendly bars and restaurants.

Allen Jones’ interview for The Unspoken Past: Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History, 1940–1970 oral history project. In 2005, Atlanta History Center opened an exhibition featuring the oral histories of LGBTQ Atlantans. Many consider it to be the first significant LGBTQ exhibition by a major historical institution.

“It was like going into enemy territory,” said Allen Jones a subject interviewed for Atlanta History Center’s Unspoken Past oral history project. “All gay people only went downtown way after dark, so nobody could see them.”

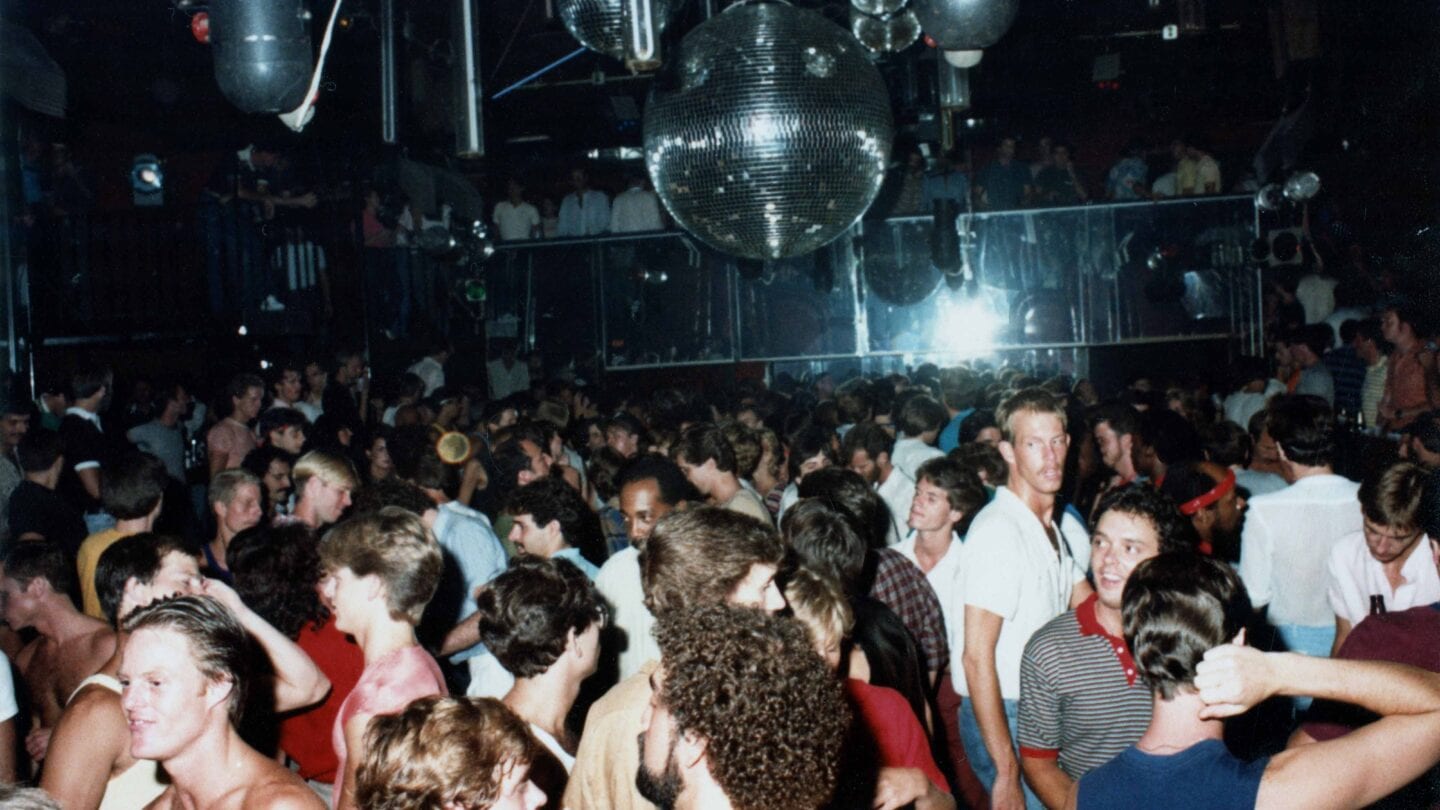

After the raid, Atlanta became the home of many gay nightclubs and bars, such as Backstreet, one of the most prominent Atlanta gay nightclubs.

Backstreet was a euphoric scene: Plush carpets, dance music, sparkly mirrored disco ball (which is now part of the permanent collection at Atlanta History Center), and three levels of bars, mirrors, and lights. Thanks to the club’s 24-hour liquor license, LGBTQ Atlantans flocked to the venue to party, often into the next afternoon.

Club-goers party at Backstreet. Sometimes called the Studio 54 of the South, Backstreet was one of Atlanta’s premier LGBTQ night clubs from 1975 until 2004 when it closed. (Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Celebrities, such as Madonna and Elton John, visited the club in disguise to experience it for themselves. Over the years, Backstreet moved away from catering to a white gay male clientele and became a gathering place for diverse members of the LGBTQ community.

During the 1970s, the efforts of Atlanta’s gay rights activists and changing social attitudes allowed the city to lay claim to becoming the Gay Mecca of the South. Only five years after Atlanta’s first small pride parade, Mayor Maynard Jackson proclaimed Gay Pride Day in 1976.

As members of Atlanta’s LGTBQ community carved out vibrant places to be themselves and display their pride without fear, the wave of change through sustained social activism has made Atlanta’s LGBTQ community one of the most progressive and diverse of its kind.

Today, Atlanta is one of only 13 cities in Georgia to have adopted local non-discrimination ordinances that protect sexual orientation and gender identity. This contrasts with the rest of the state which has a “Low” LGBTQ equality profile according to the Movement Advancement Project.

“For me, and so many outsiders like me, Atlanta is a safe space in a region that is often unsafe for us,”

“Like every other city, it has had its own reckoning with the LGBTQ community, but the progress that my hometown has achieved is remarkable.”