Lady Bird Johnson with Louise Richardson Allen and Anne Coppedge Carr, Atlanta, Georgia, 1975. Cherokee Garden Library institutional records, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Johnson was one of the most prolific environmentalists of the twentieth century, changing the national landscape even more than the institution of First Lady. Modern First Ladies establish legacies through public image and signature issues, but Lady Bird was unusual in that her public image mirrored her focus.

See America Right: Highway Beautification Act of 1965

Lady Bird’s principal image as an environmental advocate keenly reflected her signature issues of beautification, preservation, and conservation. She is remembered less for what she wore and more for what she accomplished as a savvy legislative strategist who transformed the American landscape.

“Where flowers bloom, there blooms hope.”

The competent businesswoman who ran a successful broadcasting company was as sensitive to beauty as she was canny, and her focus during the White House years shifted the spotlight from herself onto something that concerned all Americans: the environment. Lady Bird’s efforts directly impacted legislative strategy and public policy. The passage of the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, commonly referred to as Lady Bird’s Bill, eradicated much of what she called the “solid diet of billboards” and junkyards that proliferated the nascent interstate highway system begun during the Eisenhower administration. It also established vast acres of wildflowers along roads and byways throughout the country, gifts that we continue to enjoy today.

At the signing of the Highway Beautification Act into law, President Lyndon B. Johnson hands a signing pen to Lady Bird Johnson. October 22, 1965 | LBJ Library photo by Frank Wolfe (Serial Number: 786-8)

In addition to her outspoken advocacy of the Highway Beautification Act, Lady Bird Johnson transformed Washington, D.C., into a city of gardens. Cleaning the streets of litter and planting daffodils and cherry trees throughout the nation’s capital, she aimed for “masses of flowers where masses pass.”

Wholistic Environmentalism

But beautification meant more to Lady Bird than planting flowers. It meant speaking out against damming the Grand Canyon, logging in the redwood forests, and pollution. Lady Bird used her platform to advocate for expanded and improved outdoor recreation areas, mental health services, and public transportation. She viewed these as integral parts of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, a complex series of domestic programs whose main goal was the elimination of poverty and racial injustice in America. Lady Bird knew well the effects that beauty has on people to comfort, inspire, and instill pride. In a democracy, she felt, every citizen should enjoy equal access to the nation’s natural gifts, “clean water, clean air, clean roadsides, safe waste disposal, and preservation of valued old landmarks, as well as great parks and wilderness areas.”

Though largely forgotten today, the Johnson Administration was historically one of the most active in environmental conservation, due in no small part to Lady Bird, who has been dubbed “the Greenest First Lady.” This alone thrust her further into the political arena than even Eleanor Roosevelt. She revolutionized the institution of First Lady by establishing her own staff and creating procedures and tactics for this evolving role. A supportive staff was essential for a woman involved in major legislative initiatives like the Wilderness Act of 1964; the Clean Air Act; the Land and Water Conservation Fund; the Wild and Scenic Rivers Program; many additions to the National Park system; and over 200 laws pertinent to the environment.

Her dedication continued four decades after she and her husband left the White House. She visited Atlanta many times in conjunction with her work. During one trip in 1975, she presented wildflower awards for highway beautification at a Garden Club of Georgia luncheon.

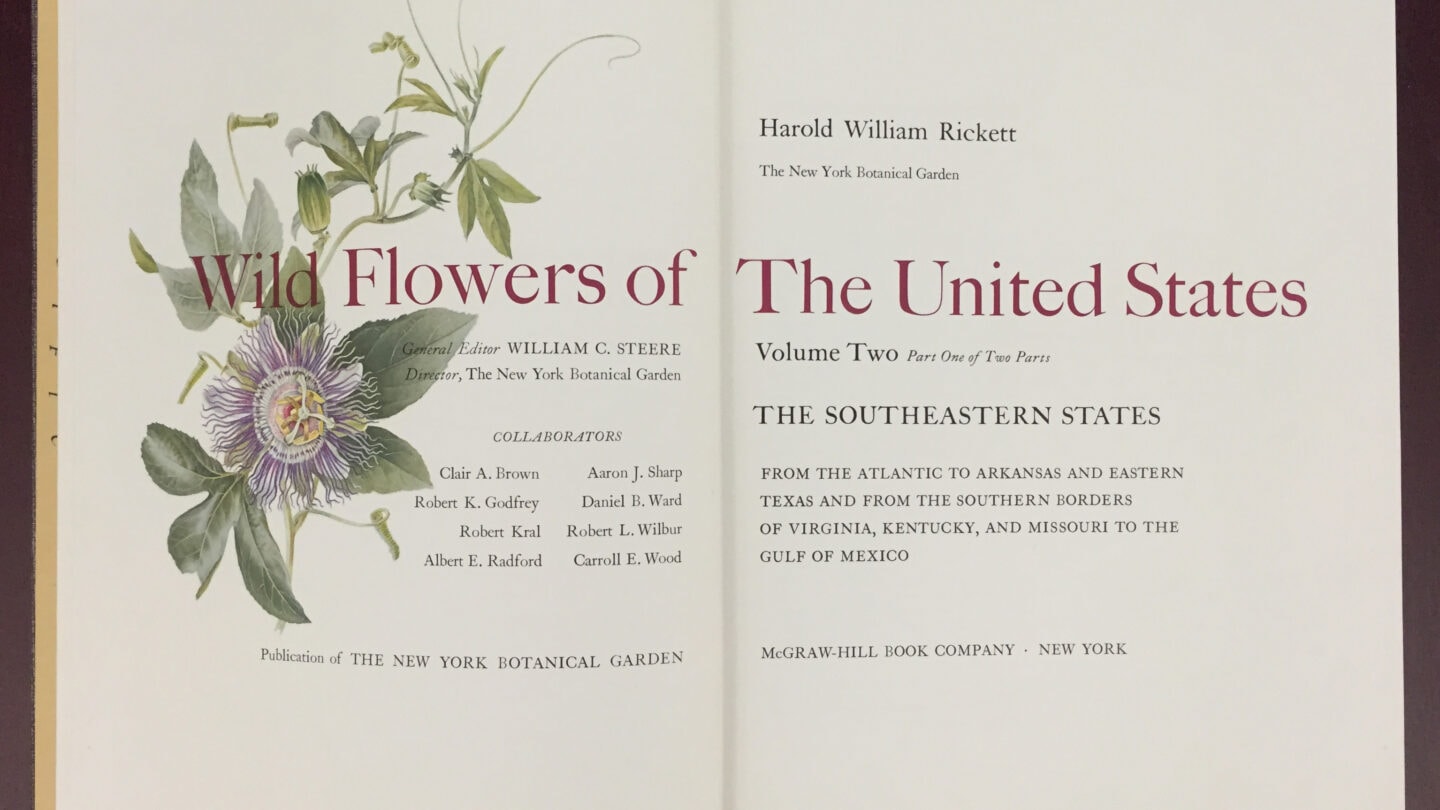

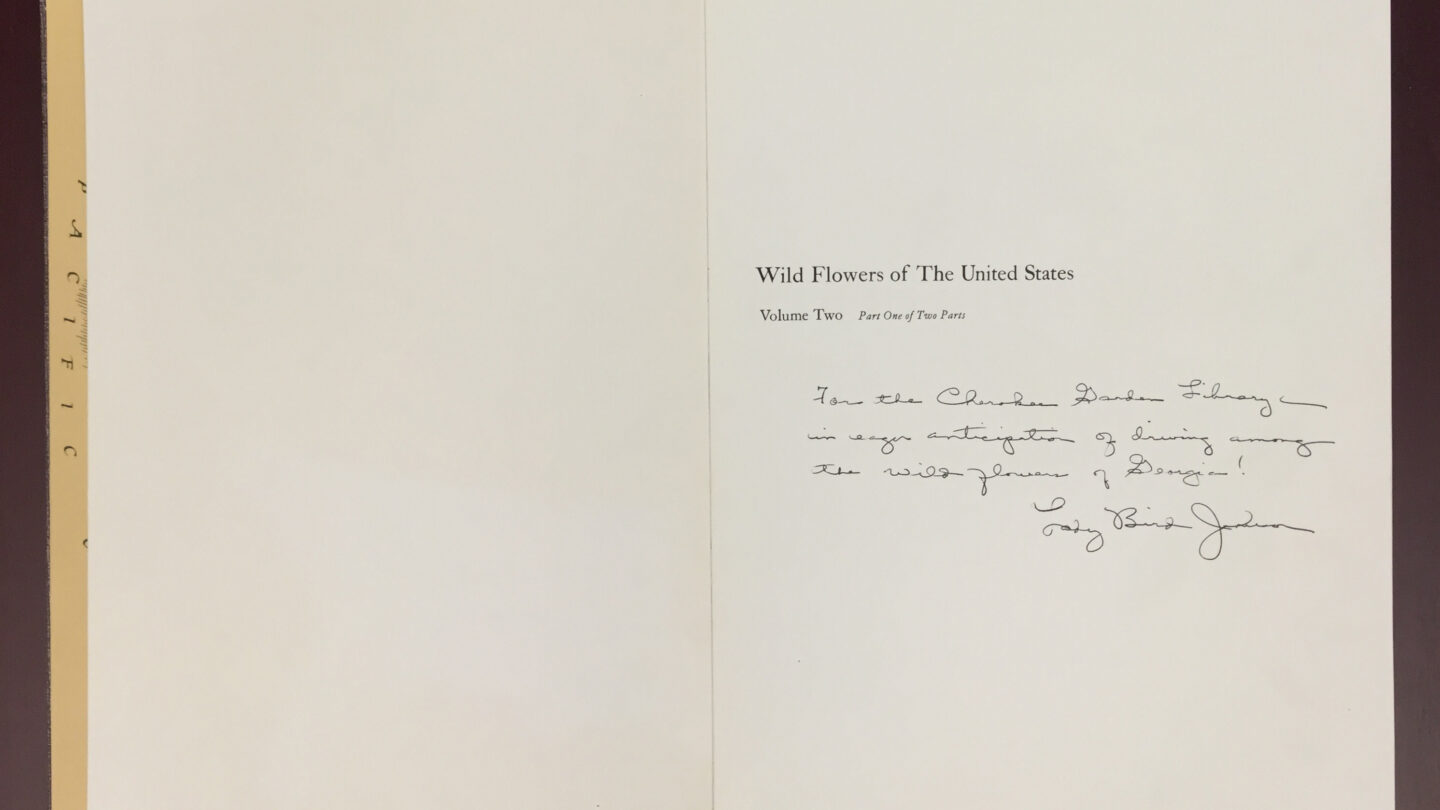

On the same trip, she visited with Louise Richardson Allen and Anne Coppedge Carr, who, along with her fellow Cherokee Garden Club members, established the Cherokee Garden Library in 1975. Lady Bird inscribed the Cherokee Garden Library’s two-volume work entitled Wild Flowers of the United States: the Southeastern States. The library owns the entire fourteen-volume collection of the renowned series by Dr. Harold Rickett. Published between 1966 and 1973, it is divided into four geographical regions in addition to two separate volumes on Lady Bird’s beloved Texas.

On the centennial of Lady Bird’s birth, her biographer, Lewis Gould, wrote that one of her greatest accomplishments was advancing “an ethic of environmentalism.” Addressing the American Institute of Architects in 1968, she described a new type of conservation that was “a concern for the total environment—not just the individual building, but the entire community.” Joining forces with Keep America Beautiful that year, her words were as applicable then as they are today: “Ours is a blessed and beautiful land. But much of it has been tarnished. What can you do? Look around you: at the littered roadside; at the polluted stream; the decayed city center.”

“We need urgently to restore the beauty of our land.”

Today, Lady Bird Johnson’s visionary work offers inspiration for a new generation to protect the natural environment for all life on the planet. At Atlanta History Center, visitors keen to learn about the history of Georgia’s abundance of native plant species can visit our Cherokee Garden Library.

Housed in the Kenan Research Center, Cherokee Garden Library contains over 32,000 books, photographs, manuscripts, seed catalogs, and landscape drawings—including a copy of Wild Flowers of the United States inscribed by Lady Bird Johnson. These rare and valuable resources tell the story of horticulture and botanical history in the Southeastern United States and areas of influence throughout America, Europe, and Asia.

For even more information about Cherokee Garden Library, please contact Garden Library Director, Staci Catron, at 404.814.4046 or scatron@atlantahistorycenter.com.

Originally from Houston, Texas, Melissa Deakins Stang has lived in Atlanta since 1970. She holds a master’s degree in English and is a freelance editor, a gardener, and an avid adopter of retired greyhounds.