Hank Aaron, a legendary baseball player, advocate for racial equality, and the historic breaker of Babe Ruth’s 714 home run record, has died. On and off the field, he contributed greatly to the athleticism and the progress of equal opportunity within the sport. He had an eight-year career with the Atlanta Braves and has additionally made several substantial philanthropic contributions to HBCUs in Georgia. We join the city of Atlanta and the global baseball community in mourning his passing.

The third of eight children, he was born Henry Louis Aaron in Mobile, Alabama, in 1934 to Estella and Herbert Aaron, a tavern owner and a dry dock boilermaker’s assistant. Once they were old enough to work, each of the Aaron children took on one or more jobs to support the family. Mr. Aaron picked cotton and did a handful of other small jobs.

Early in life, he became interested in baseball.

When he wasn’t working or attending school, he began perfecting his batting abilities, which he initially did by hitting bottle caps with a broom handle.

Mr. Aaron preferred playing and learning about baseball to his schooling experience. In 1947, he even skipped school to watch Jackie Robinson give a talk in Mobile when the Dodgers visited the city to play an exhibition.

For his freshman and sophomore years of high school, Mr. Aaron went to Central High School, a segregated Mobile public school. While there, he played football for the school and baseball in a small, independent league. He transferred to the Josephine Allen Institute, a private school with an organized baseball program, to finish his final two years of high school. During this time, he played on the semi-pro Mobile Black Bears team and earned $3 per game. Mr. Aaron’s mother allowed him to play with the team on the condition that he only play in local events.

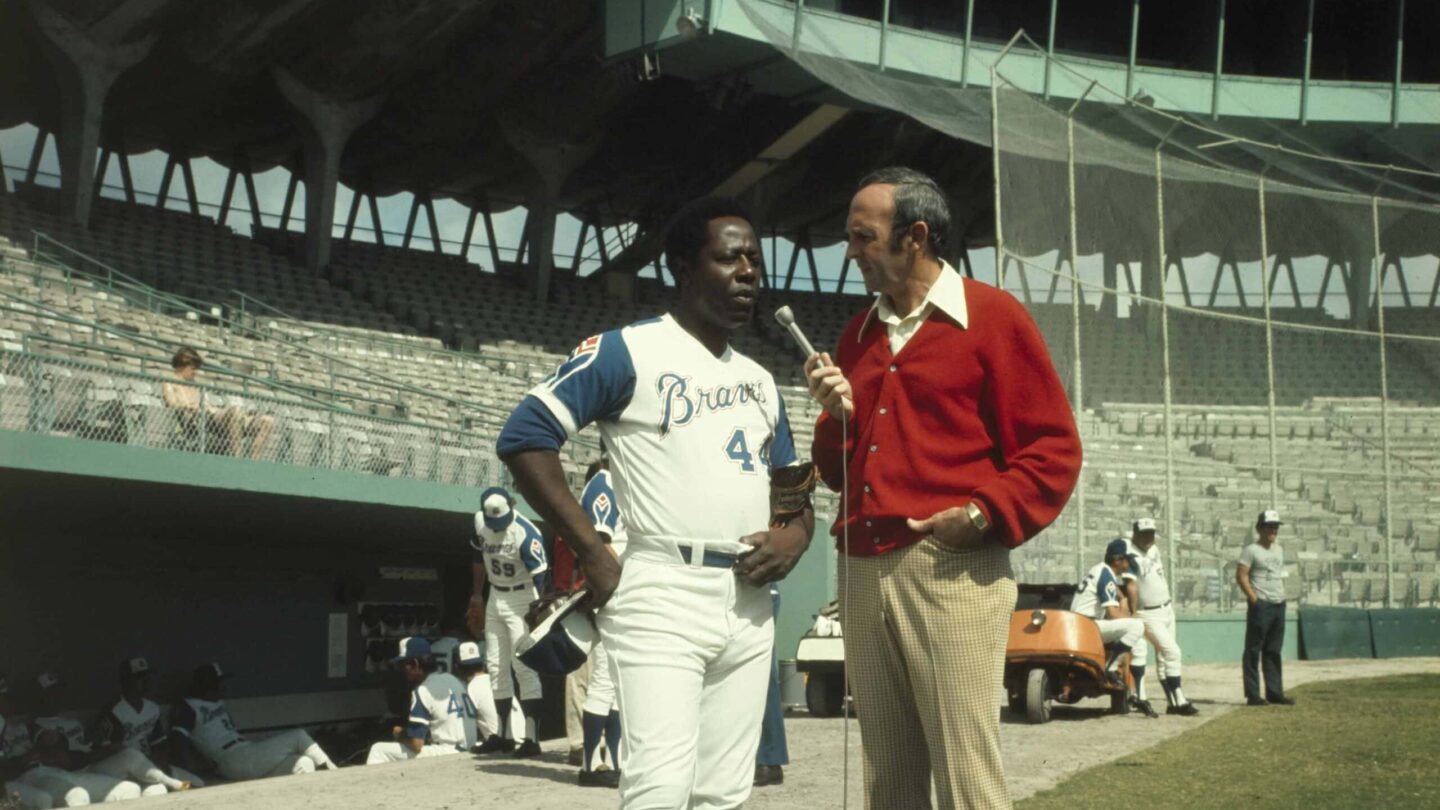

Hank Aaron at bat during an Atlanta Braves baseball game at Atlanta Stadium (Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium) in 1973. (VIS 71.371.03, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center)

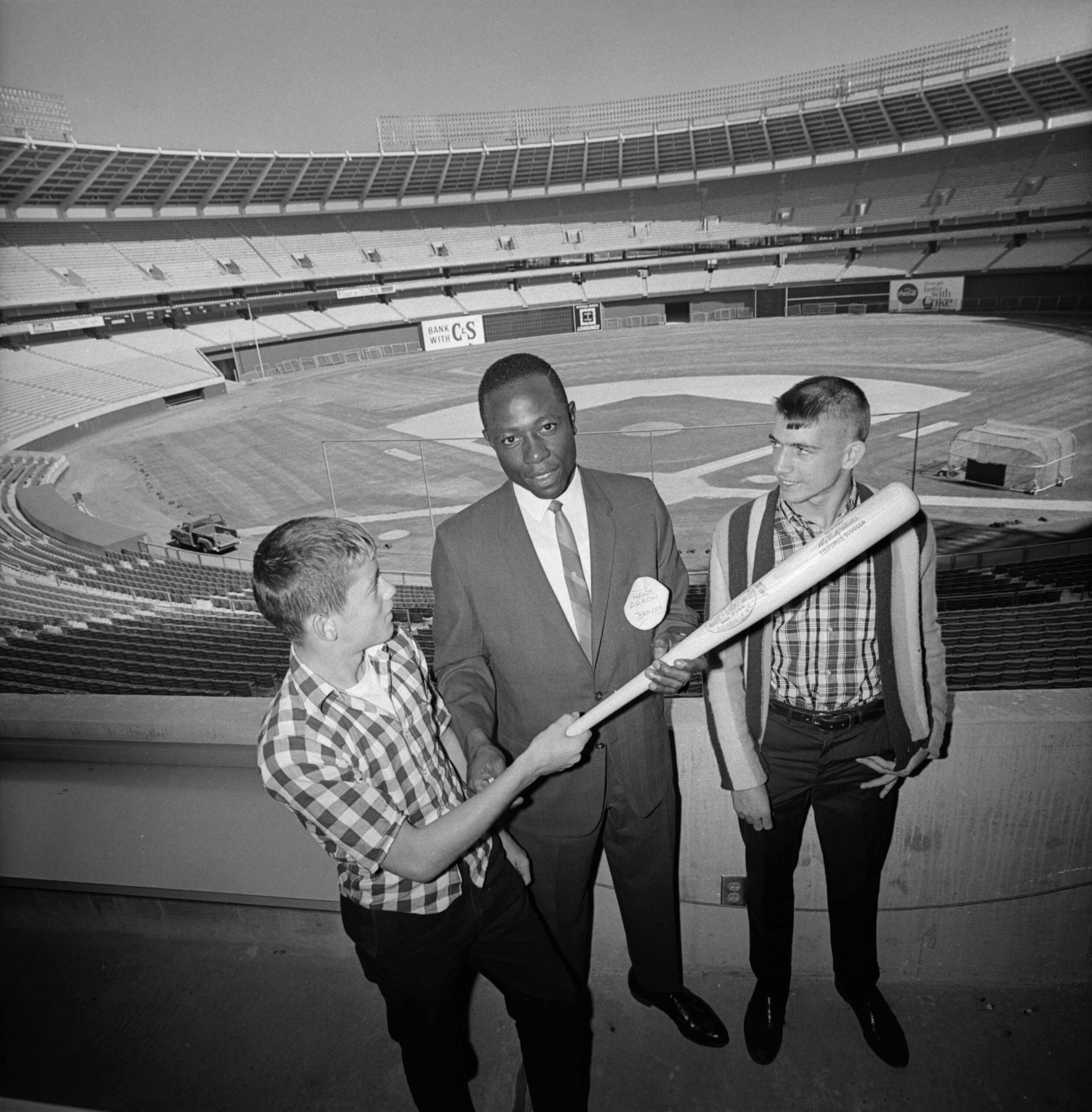

In 1951, he signed a $200 per month contract with the Negro American League’s Indianapolis Clowns, even though his mother wished for him to continue his education by going to college. After only a year on the team, Mr. Aaron helped lead the Clowns to victory in the 1952 Negro League World Series. This success propelled him to a contract with the Milwaukee Braves for $10,000, where he was assigned to one of the organization’s so-called “farm clubs,” the Class C Eau Claire Bears. As a member of that team, he earned Northern League Rookie of the Year honors and was then promoted to the Class A Jacksonville Braves in 1953. Upon joining the Jacksonville Braves, Mr. Aaron became one of only five African American players in the newly desegregated minor South Atlantic, or Sally, League. His time on the road with that team required him to endure racially-motivated taunts from fans as well as more overt forms of discrimination. Despite these disadvantages, he earned MVP honors from the league that year in addition to meeting Barbara Lucas, the woman who would become his first wife.

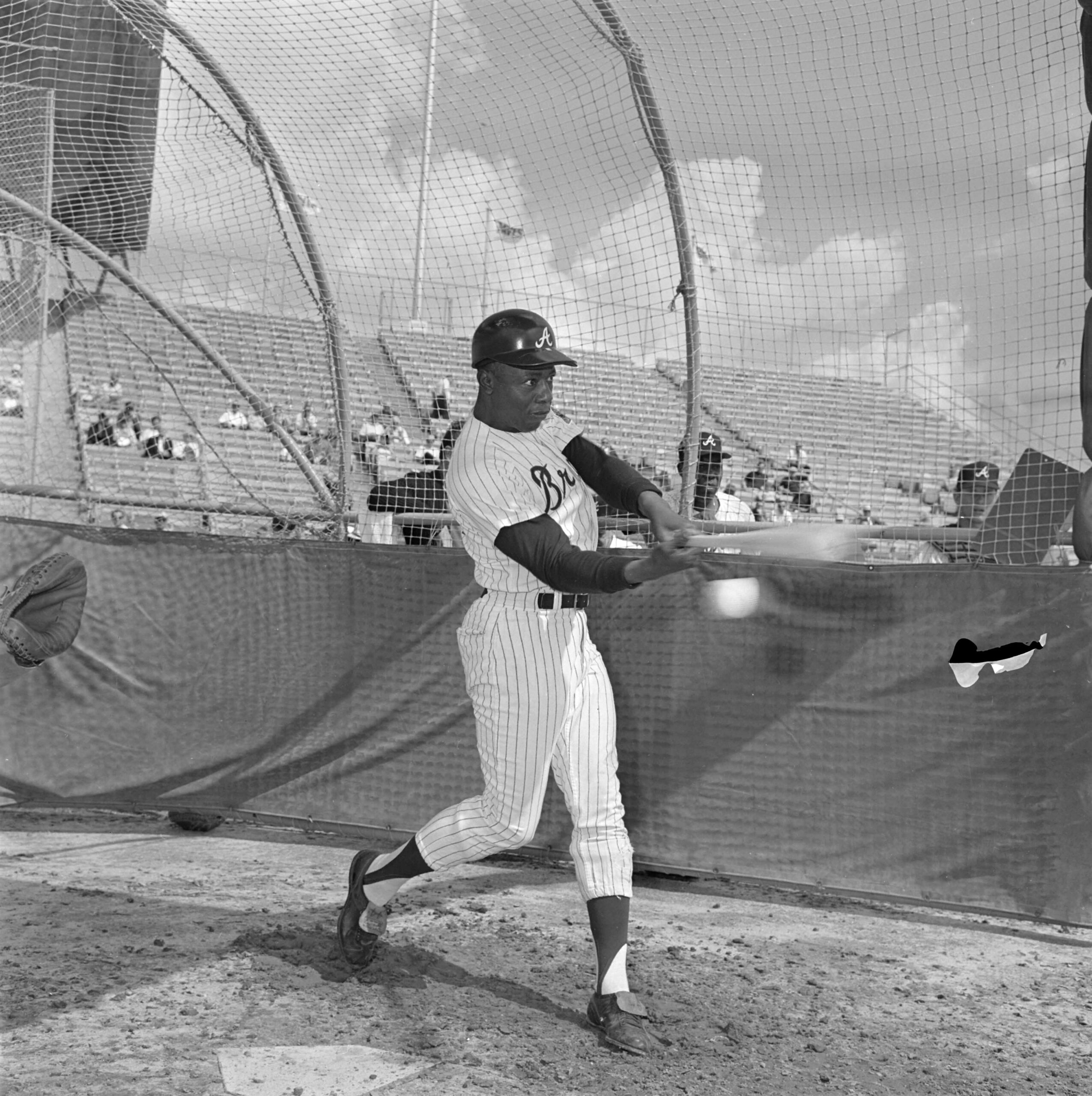

Mr. Aaron was further promoted to the major league Milwaukee Braves in 1954 at the age of 20, after his teammate sustained a spring training injury and freed up a spot on the roster. He won his first batting title in 1956 and was awarded the National League MVP following a remarkable 1957 season. That year, he helped carry Milwaukee to the World Series and eventually to an upset, seven-game victory against the New York Yankees.

By 1959, he was paid roughly $30,000 per year in salary and just as much from endorsements. Motivated from his increasing popularity and his successful use of power when he was up to bat, Mr. Aaron decided to quite literally swing for the fences as much as possible. This decision led him to a 30 to 40 home run record each year for 15 years. He was hard working, humble, and shy, characteristics that fans celebrated in white players, but that they found mysterious and untrustworthy in Black ones. Because of this, he didn’t have much fan appeal in the early part of his career.

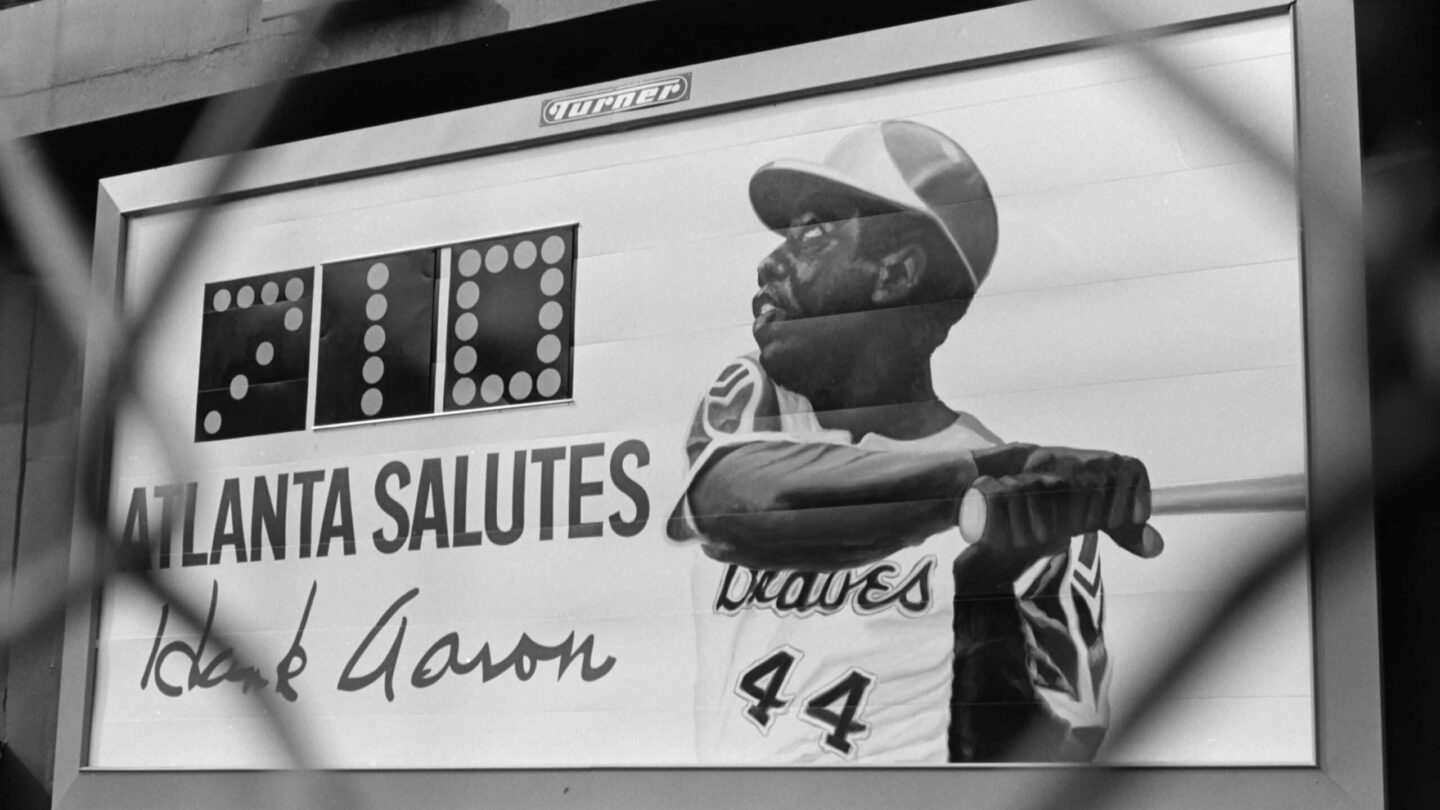

View of a billboard saluting Hank Aaron as he approached Babe Ruth’s home run record, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, September 15, 1973. (VIS 101.584.001, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center)

The Milwaukee Braves moved the franchise and became the Atlanta Braves in 1966, bringing Mr. Aaron with them to the South. For their first few years in Atlanta, the team maintained a relatively steady 50/50-win-loss record. Mr. Aaron remained the hitting star of the team and, at 39 years old, finished the 1973 season with a career total of 713 home runs, only one behind the record of the legendary Babe Ruth.

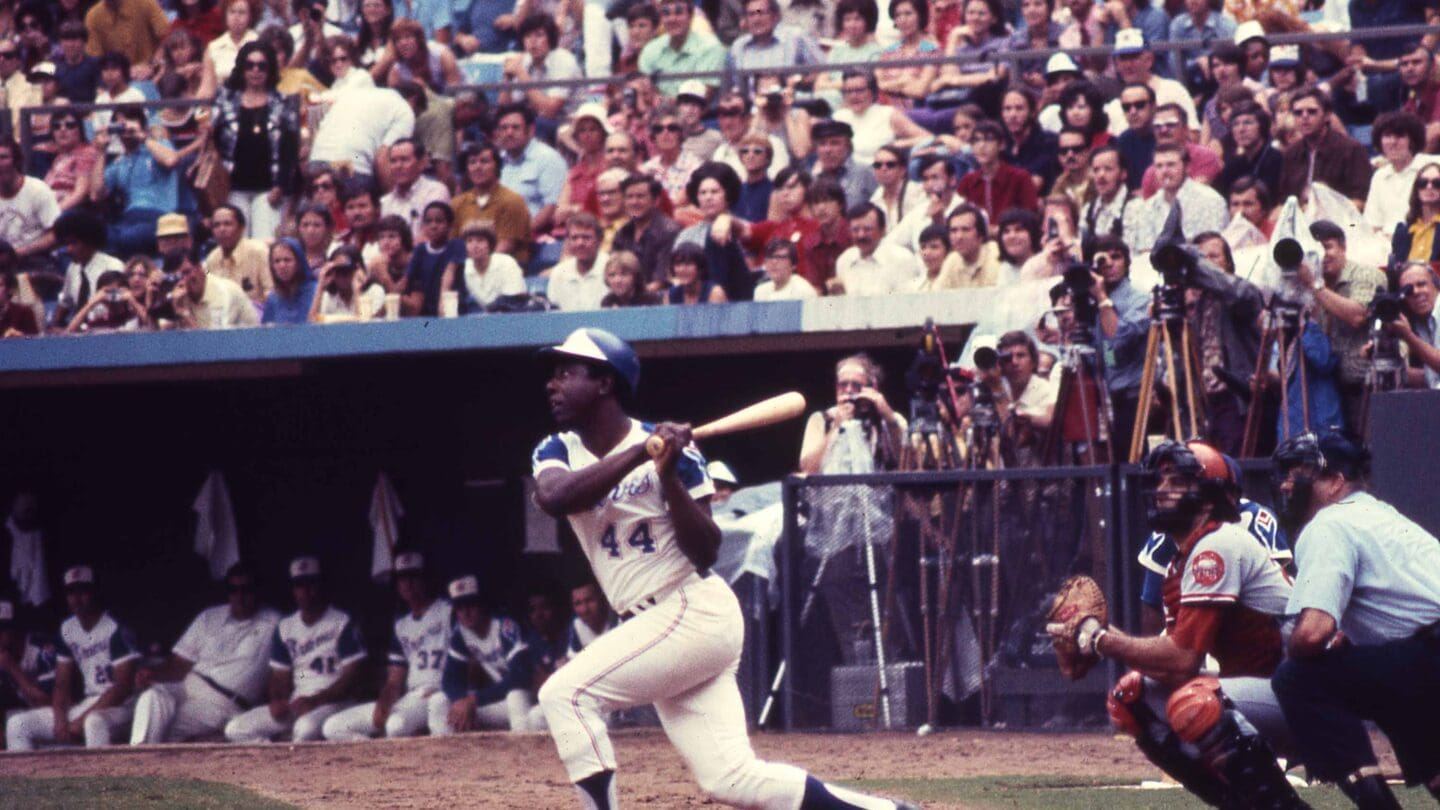

He hit his 715th home run on April 8, 1974 off of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ pitcher in front of a sold-out home game crowd.

Over 50,000 fans cheered Mr. Aaron and his accomplishment as he rounded the bases at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. He was celebrated with fireworks and a live band, and his parents congratulated him on the field when he crossed home plate. It was a historic day for Mr. Aaron, his family, the city of Atlanta, and the entire sport of baseball.

Some people, however, were angry that a Black man had attained such success and broken one of baseball’s most cherished records. Intermixed with messages of support and congratulations, Mr. Aaron received several death threats and racialized, hateful comments. Despite the direct threats he experienced, he chose to advocate for himself and for his fellow players of color, speaking out against the National League’s lack of opportunities for minorities, especially in ownership and management positions.

After breaking Babe Ruth’s record with the Atlanta Braves, Mr. Aaron played for two years with the Milwaukee Brewers and retired upon finishing the 1976 season. Following the conclusion of his career as a player, he joined the Atlanta Braves front office as an executive vice president and became a spokesman for minority hiring in baseball. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982 and awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002.

For nearly the past three decades, Mr. Aaron and his wife, Billye Aaron, established themselves as generous, philanthropic contributors to American education and sport. The couple’s Atlanta-based Chasing the Dream Foundation has awarded scholarships to grade school and college-aged students since its founding in 1995. Mr. Aaron also gave Morehouse School of Medicine, a department in one of Atlanta’s HBCUs, $3 million in 2015. The school used this funding to expand the Hugh Gloster Medical Education building on campus and helped create the Billye Suber Aaron Student Pavilion.

Mr. Aaron was not only an iconic figure in baseball, but a dedicated man and a committed contributor to the success of our city and its residents. We will remember the mark he left on Atlanta and on baseball.