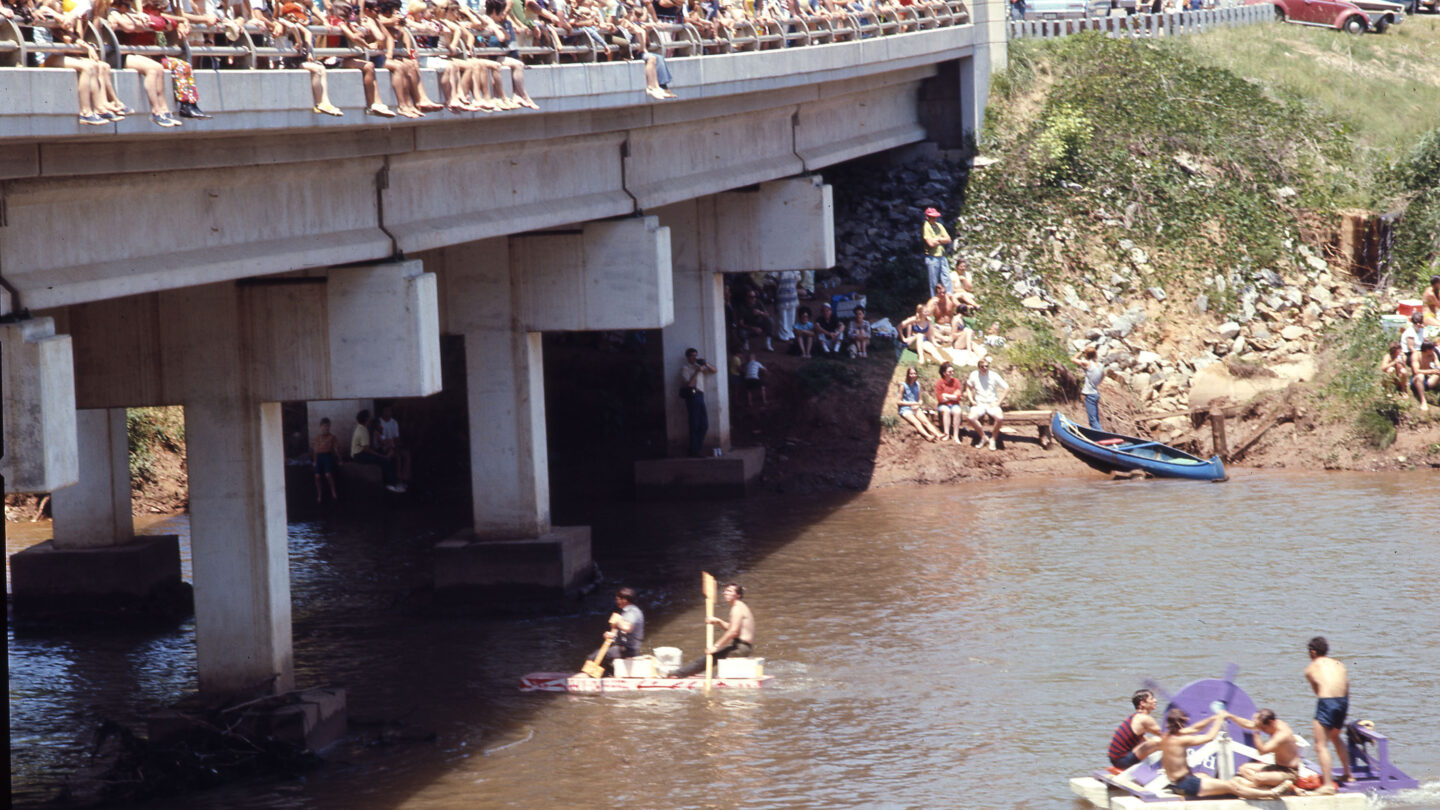

Spectators watch participants race in the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Picture the cold, slow-moving, and sometimes muddy waters of the Chattahoochee River. Makeshift rafts of all shapes and sizes float downstream, their designs contrast with the river’s natural hues. Laughter and the sounds of splashing water fill the air as participants navigate the winding, tree-lined banks of the river. This isn’t just a leisurely float but a spirited race, with rafters paddling fiercely amid cheers from the crowded banks. The sun glints off the water, casting a golden glow on the scene, while music and the spirit of competition create a lively atmosphere. This was the Ramblin’ Raft Race—an event that would come to define Memorial Day weekends for more than a decade.

Competitors race to win the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Beginnings and Boom

In 1969, Delta Sigma Phi, a fraternity at Georgia Tech, organized the Ramblin’ Raft Race as a modest social event on the Chattahoochee River. The race quickly garnered the attention of WQXI, a local AM radio station. WQXI became a sponsor and promoter of the event, transforming it into a spectacle of epic proportions. By the mid-1970s, the event had grown into a massive annual gathering, at its peak drawing more than 300,000 participants and spectators.

Participants compete in the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

A Festival of Rafting

The race’s route was as scenic as it was challenging, commencing at Morgan Falls Dam in Sandy Springs and concluding a few hundred yards north of I-285 in Vinings. Participants navigated the Chattahoochee on makeshift rafts, each more creative and colorful than the last. The event was not just about the thrill of racing; it became synonymous with a carefree, celebratory spirit.

However, the event was not without its darker side. The raft race was infamous for the rampant consumption of alcohol and, often, illegal drugs. The rowdiness that ensued led to increasing concerns from property owners along the river, who were troubled by the public drunkenness, nudity, and environmental degradation caused by the revelers.

View of participants in the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

National Attention and Notoriety

The scale of the Ramblin’ Raft Race did not go unnoticed. It captured the attention of national and international media, with coverage by CBS News anchor Dan Rather and even a mention in a French documentary about the Chattahoochee. The Guinness Book of World Records once dubbed it the world’s largest participant sporting event, a testament to its massive draw.

Yet, with popularity came scrutiny. By 1978, environmental concerns had reached a crescendo. President Jimmy Carter, in a nod to growing conservationist sentiments, signed a bill establishing the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area. The National Park Service found itself stretched thin, budgeting an extra $50,000 to manage the race crowds by 1980.

A crowd watches the Ramblin’ Raft Race along the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The Final Stretch

The race’s final years were marred by increasing tensions. In 1980, local authorities began a crackdown, issuing citations for public drunkenness and towing an estimated 4,000 cars. Tragically, that year’s race also witnessed its first and only drowning, a sobering event that underscored the race’s inherent risks.

Faced with escalating insurance costs and the logistical nightmare of ensuring safety and cleanup, the American Rafting Association withdrew its support. WQXI’s solo attempt to manage the race in 1980 proved unsustainable. The event’s end was sealed when the park service mandated that sponsors shoulder the full burden of security and cleanup costs—terms they found untenable.

In retrospect, Georgia Wildlife Foundation studies revealed that the rafters themselves were not the primary culprits of environmental damage. Rather, it was the spectators who posed the greater threat, trampling fragile riverbank vegetation and leaving behind a trail of litter. Despite these findings, the event’s cancellation was a necessary step toward preserving the river’s health and integrity.