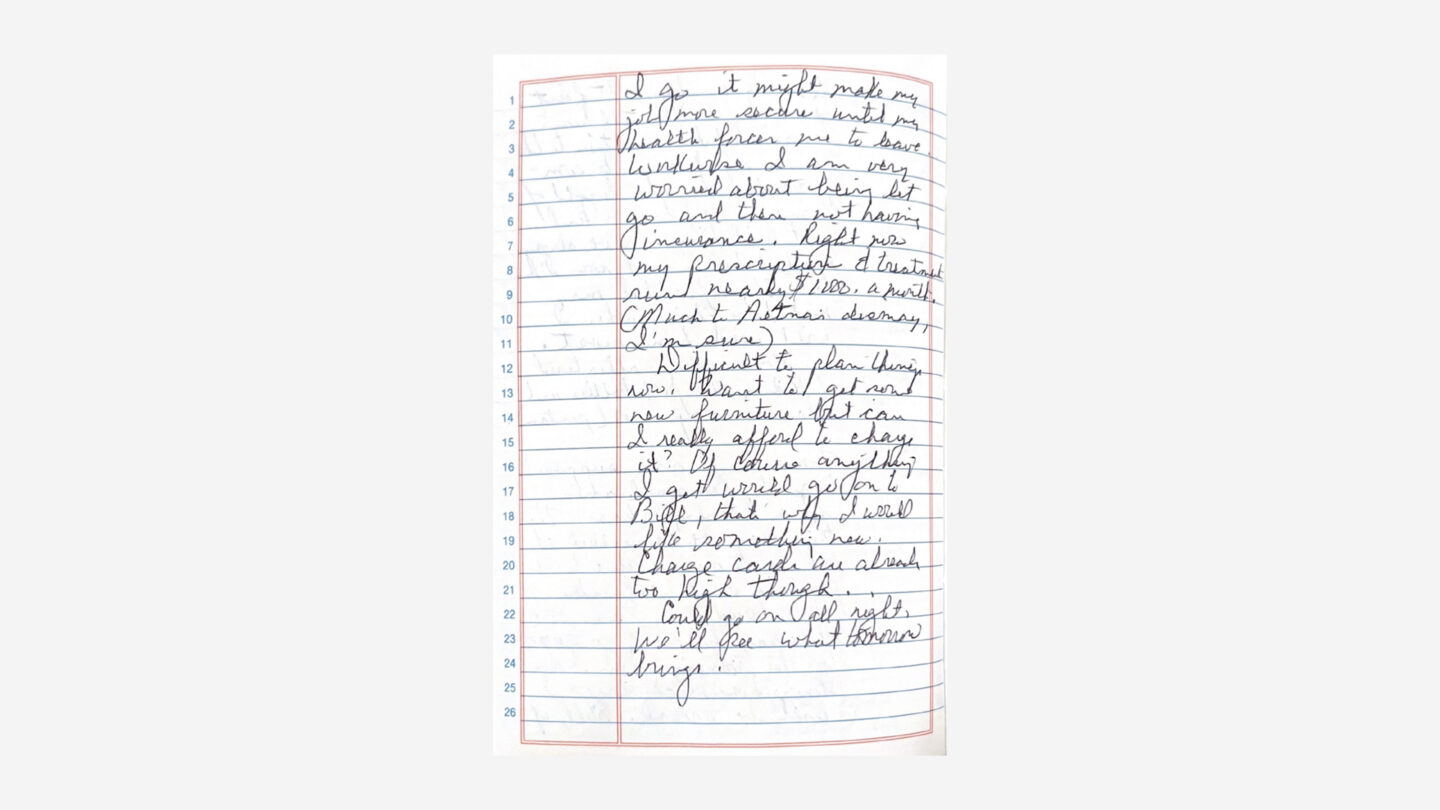

Karl Allquist, circa 1990. Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

In 1981, doctors were alarmed by increasing numbers of gay men with cases of Pneumocystis pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma, two fatal and rare illnesses typically found in immunocompromised people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began investigating that summer and discovered the disease we know today as HIV/AIDS. HIV, which is transmitted through bodily fluids, disproportionately affected gay men and intravenous drug users during the early years of its discovery. UNAIDS estimates that 85 million people have become infected with HIV since the first known cases in 1981. Of those 85 million, at least 40 million have died from HIV/AIDS-related complications.

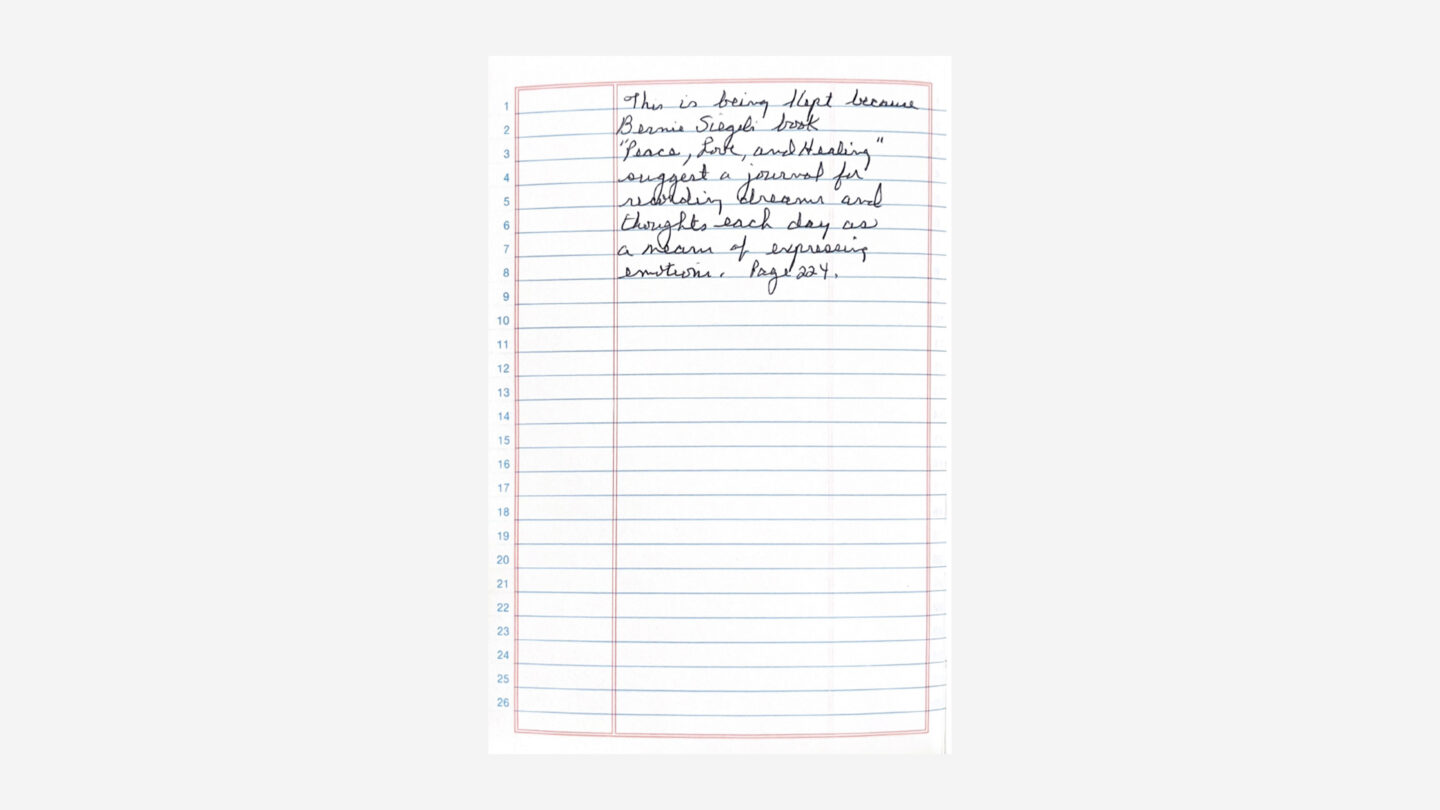

Karl Allquist was diagnosed with HIV in 1989. He kept a journal documenting his life with HIV from 1989 to 1991. Karl died in 1992 from HIV/AIDS-related complications. In 2004, Atlanta History Center interviewed Karl’s surviving partner, William “Bill” Penn, as part of Atlanta’s Unspoken Past Oral History Collection, where Bill detailed his relationship with Karl and losing him to HIV/AIDS.

William “Bill” Penn’s Oral History Interview. Atlanta’s Unspoken Past Oral History recordings, VIS 178.008.001, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Their story together began in 1968 when Bill moved to Atlanta from West Virginia. While Bill had a core group of friends back home, Atlanta was a completely new territory. Eager to meet new people, he began going to gay bars, and one weekend he saw Karl Allquist while ordering a drink. Initially, Karl rebuffed Bill’s advances, but by the third weekend of Bill hanging out by the bar, Karl was ready to get to know him.

Bill had a place in Atlanta, while Karl had a home in Tucker. They started spending more and more time together and eventually split their time between their “city” and “country” homes. This was the beginning of an 18-year relationship. Bill worked for Belk, and Karl worked for a computer company. Both traveled for work throughout the week. The two had a mutual understanding that they didn’t have a monogamous relationship, but they never openly discussed it. On one business trip, Karl contracted HIV and was diagnosed with the virus in March 1989.

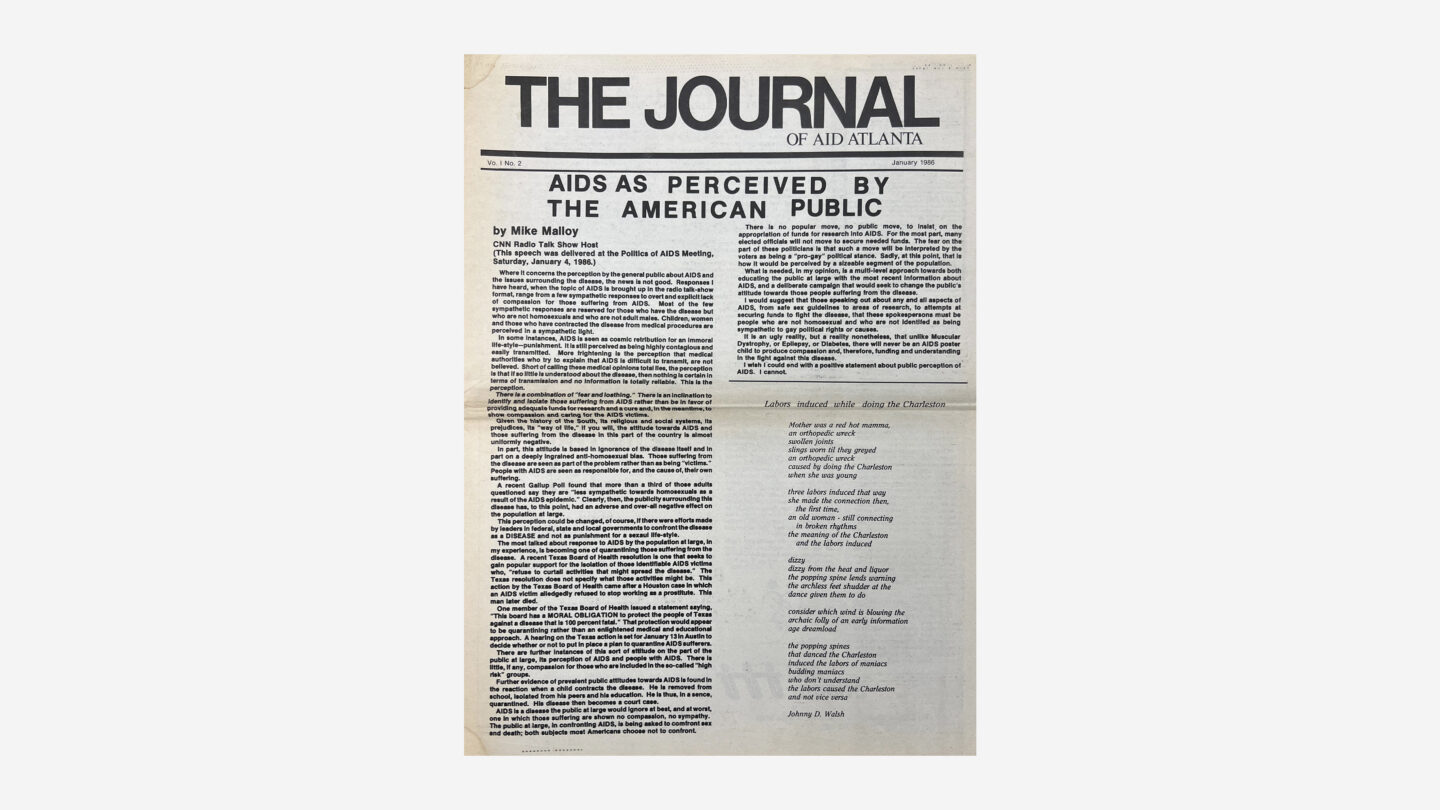

Members of the LGBTQ+ community organized early on. They demanded better access to healthcare for HIV/AIDS, prevention awareness, and dispelling myths surrounding infection. AID Atlanta has provided HIV/AIDs medical care and education since 1982. In the 80s, the group published journals educating the public on HIV/AIDS. Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing papers and Publications, MSS773, Kenan Research Center

When Karl was diagnosed, the virus had been public knowledge for about seven years. Despite this, President Reagan had only publicly acknowledged the emerging health crisis four years prior. Congress did not pass legislation to help those suffering from the disease until August 1990 when Congress passed the CARE Act, allocating health services to individuals with HIV/AIDS.

For Karl, living with HIV was lonely and isolating. He was afraid to tell anyone, so he didn’t. Instead, he found refuge in a diary.

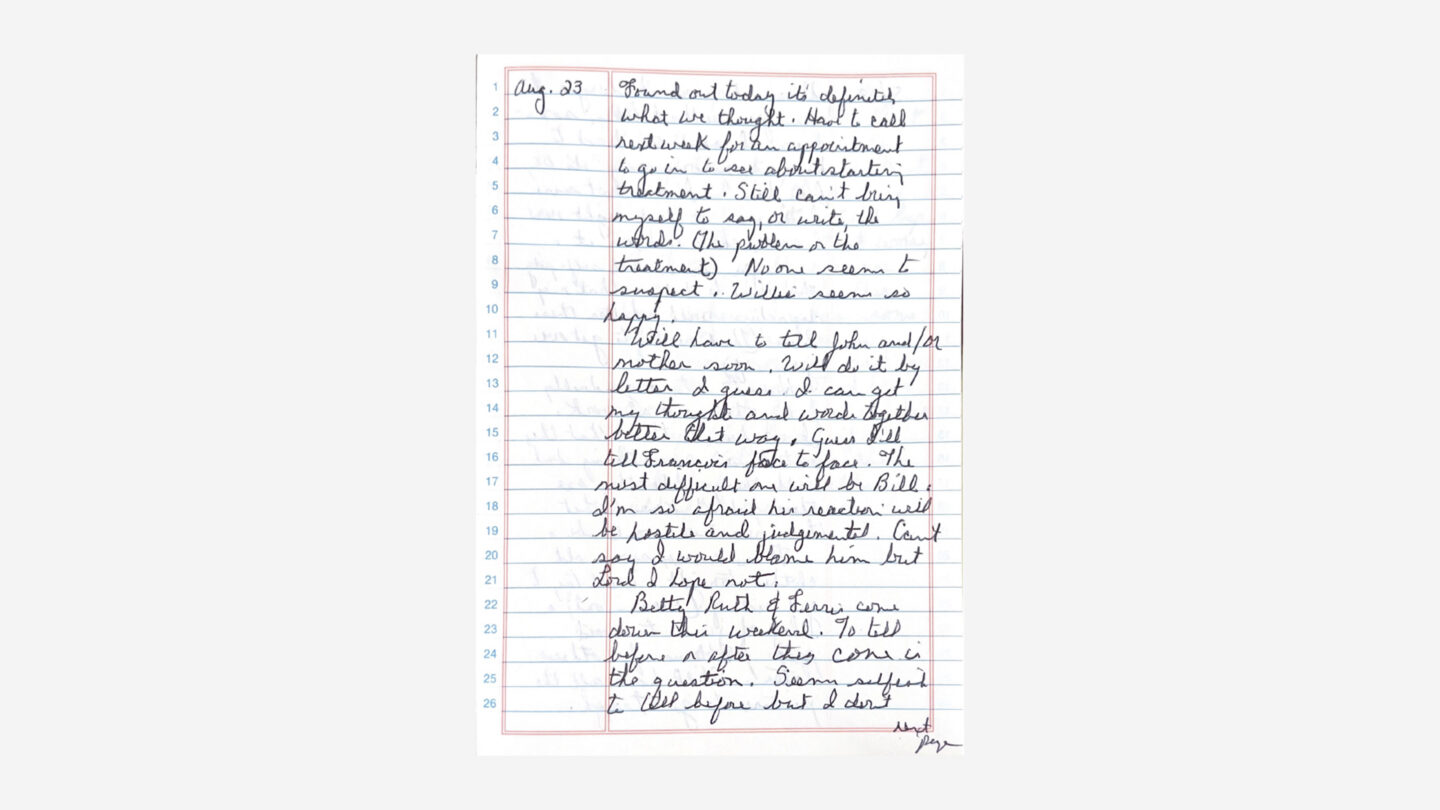

On August 23, 1989, he wrote, “Found out today it’s definitely what we thought… Still can’t bring myself to say, or write, the words… No one seems to suspect.”

He knew he needed to tell Bill but struggled to bring himself to do it throughout the journal. He started treatment in secret while continuing to work. The secret put a strain on their relationship. In Bill’s oral history interview, he noted that Karl would be gone from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. with no explanation.

Karl struggled with HIV largely alone. In September 1989, he pondered if his life insurance would be paid out in the event of suicide, and by the new year, he still hadn’t told Bill. He attended a support group occasionally, but he was scared to go too often for fear of his secret being exposed. Throughout his illness, he worried about paying for treatment. He continued to work, despite his declining health, as he needed the health insurance provided by his company to receive treatment. While his insurance covered $4,000 of his hospital bills in September 1989, Karl still had to pay $500.

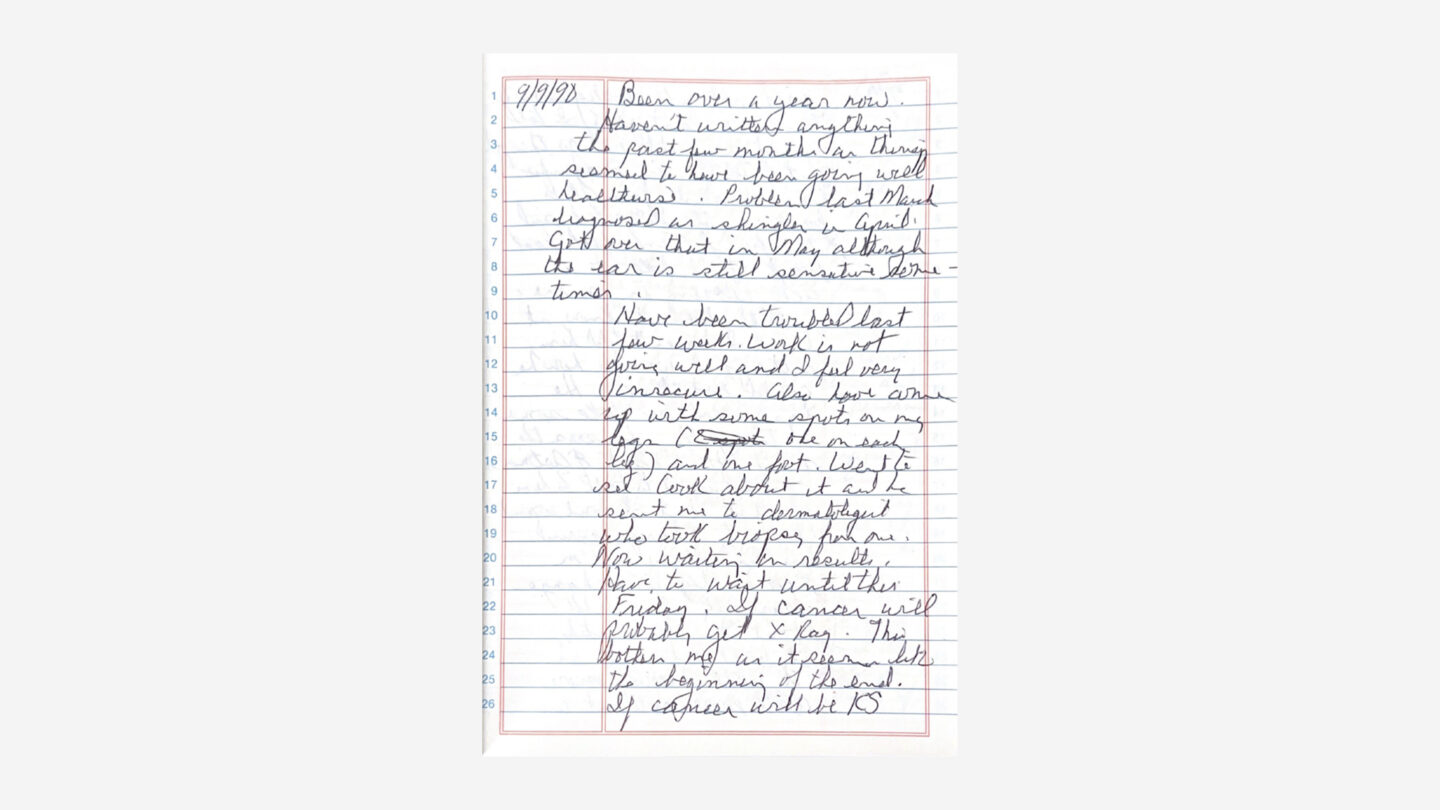

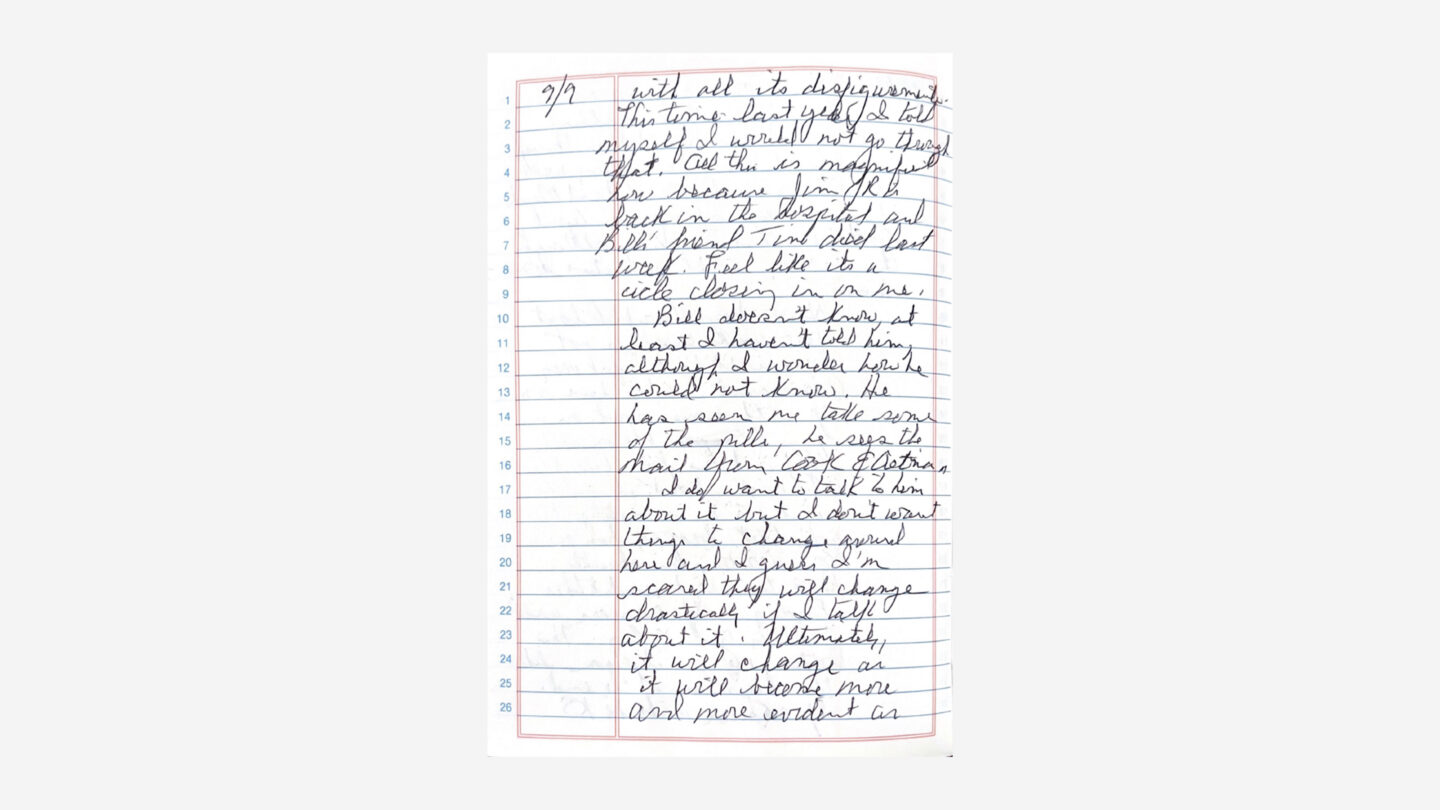

In March 1990, he was getting sick more often. He struggled with a throat and ear infection that wouldn’t go away and continued to feel weaker. He didn’t write for months and picked the journal back up again in the fall of that year. It had been a year since his initial diagnosis, and things felt more real than ever. On September 9, he wrote that the sickness was closing in on him. Bill’s friend had passed away a week prior, and death was starting to feel more imminent.

Karl still hadn’t told Bill about his diagnosis.

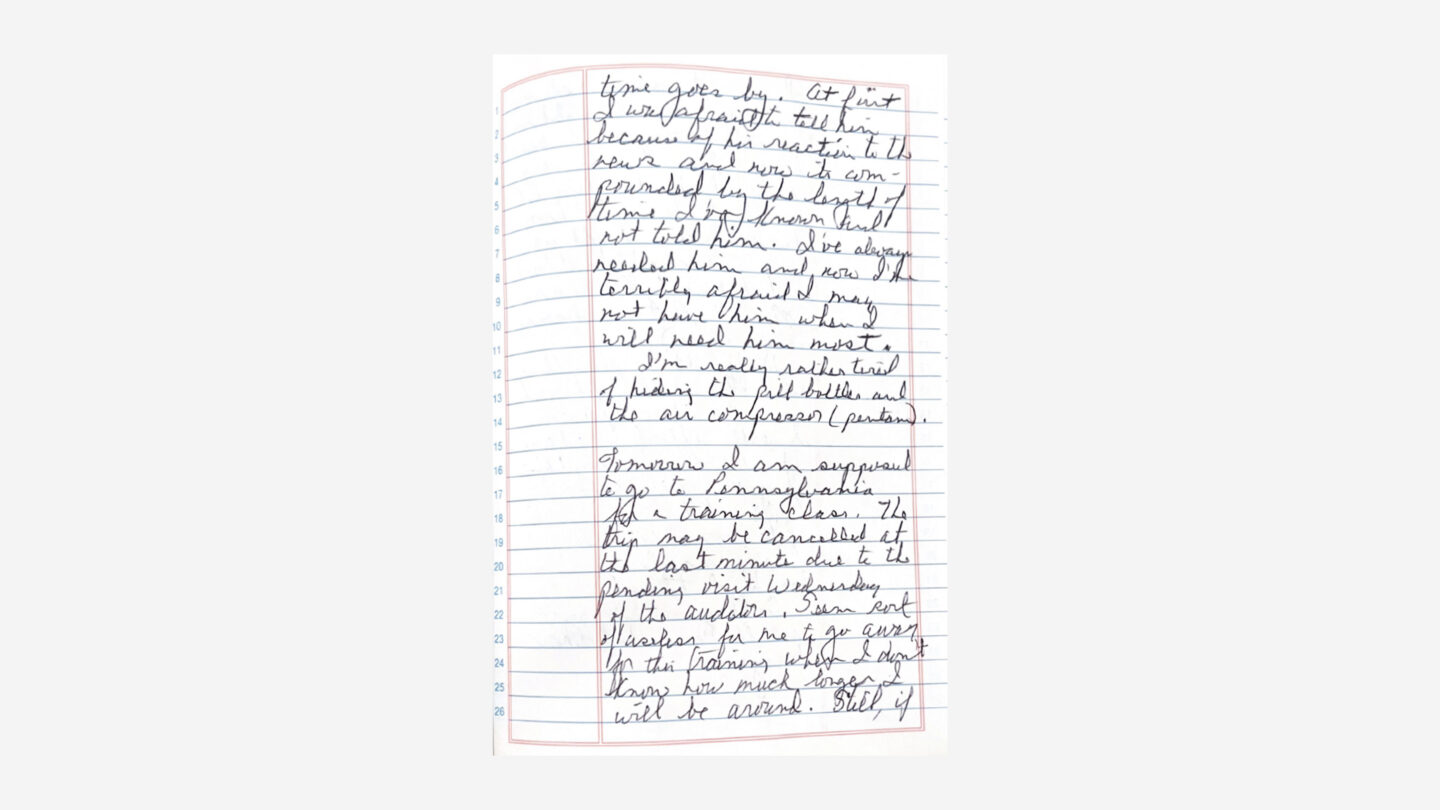

Karl wrote in his diary, “At first, I was afraid to tell him because of his reaction to the news and now it’s compounded by the length of time I’ve known and not told him. I’ve always needed him and now I’m terribly afraid I may not have him when I need him most.”

Karl’s entries became less frequent from the end of 1990 to 1991. By February 1991, Karl was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma. Despite his illness progressing, Karl still worked because he needed health insurance to pay for treatment. He couldn’t afford to quit, and his situation became even more precarious when he received a 10% pay cut in salary. He worked overtime to make up for it while struggling with complications from HIV/AIDS.

His last entry was in March 1991. He talked about being referred to an oncologist to treat his Kaposi sarcoma and struggling over continuing to hide his diagnosis from Bill. While the entries ended, Bill’s interview picked up the story. Karl finally told Bill about his diagnosis sometime in 1991.

He was terrified Bill would leave him, but Bill reassured him. “No, I’m going to stay right here,” Bill said. He immediately took over for Karl’s needs in his final days. He secured a cemetery spot, an officiator for the funeral, and all other arrangements Karl needed.

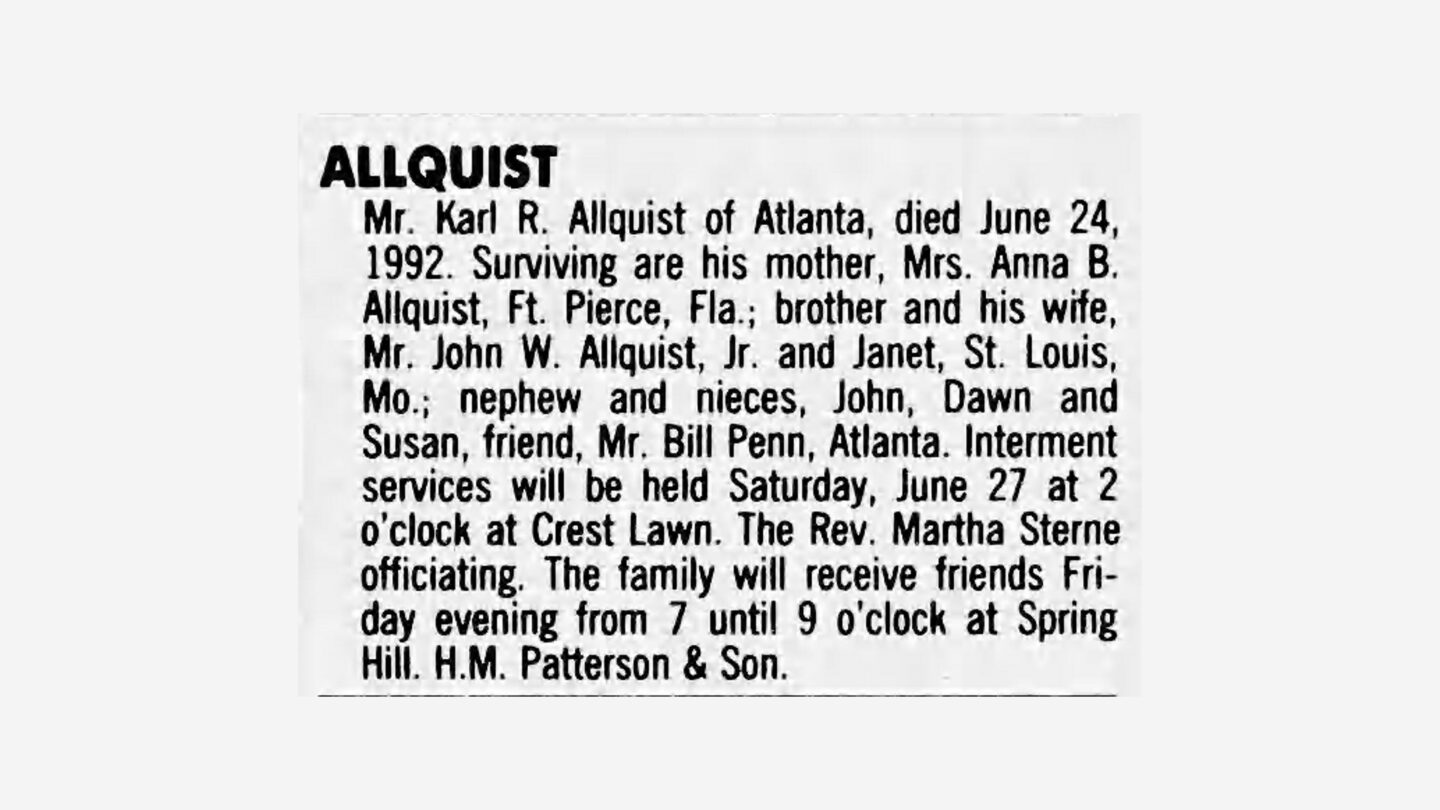

Karl Allquist died on June 24, 1992. More than 200 people attended his funeral.

“Allquist.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution. June 26, 1992, via Newspapers.com.

HIV/AIDS has existed for more than 40 years now. While new HIV infections fell 8% between 2015 and 2019 across the United States, the CDC stated that the rate of HIV infection in Atlanta was an epidemic in 2018. In 2022, Georgia was the number one state for new HIV infections. The only way to stop the spread of HIV is preventative care and ongoing treatment for those infected. If you or someone you know may have been exposed to HIV, the CDC’s locator for free HIV, sexually transmitted disease, and hepatitis testing can help you find a location. AID Atlanta is a local organization that has provided HIV/AIDS related services since 1982. To learn more about their services, visit their website.