MSS 1011, Harry G. Lefevre Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

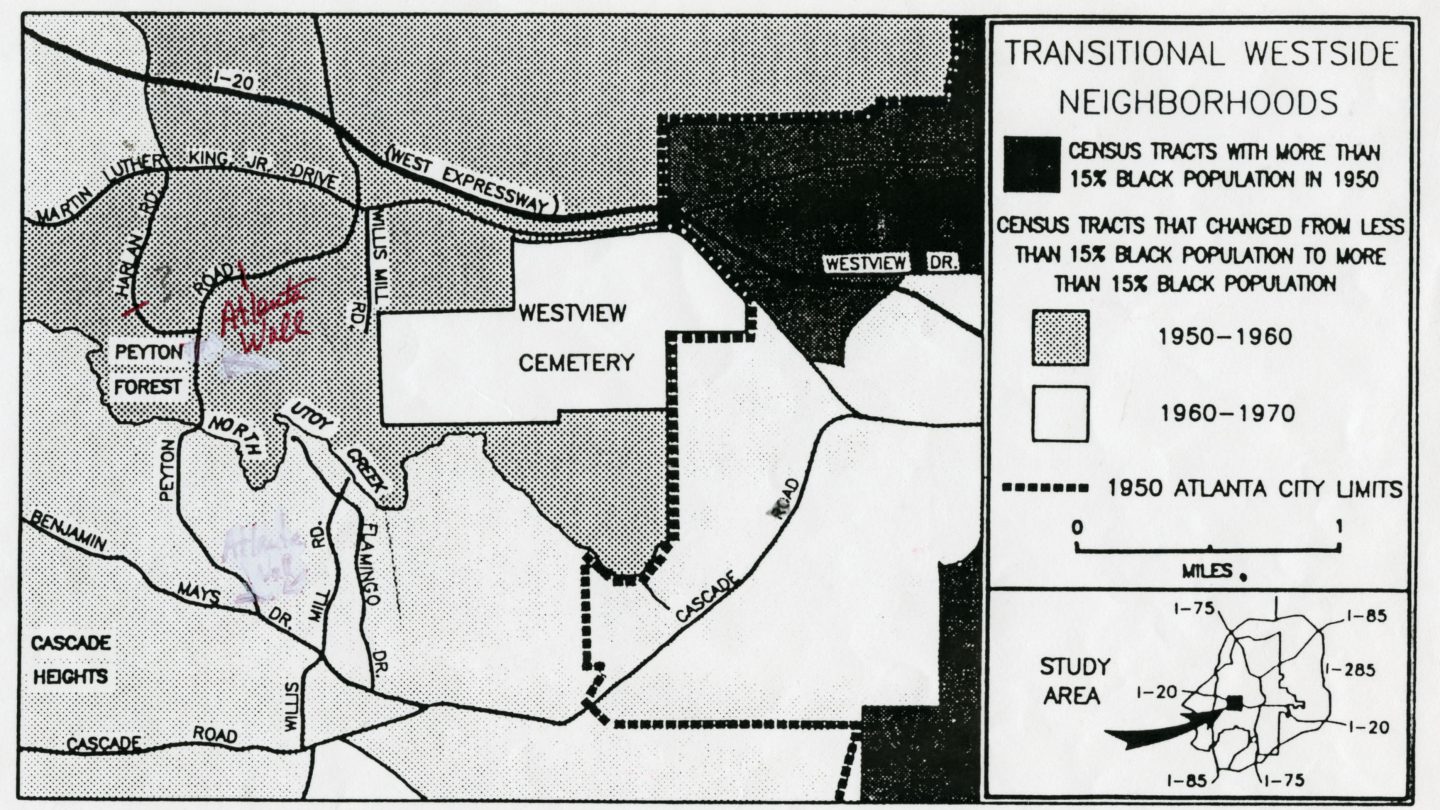

On December 17, 1962, Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. ordered the construction of a wooden roadblock across Peyton Road in southwest Atlanta. The barricade severed the main line connecting the white and Black sections of the Cascade Heights neighborhood. Drivers, diverted from their normal routes, were forced to access the neighborhood via side streets, adding up to five miles to car journeys and making travel inconvenient along the important north/south roadway.

Hand-annotated map excerpted from Ronald H. Bayer’s Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta indicating the location of the barricades on Harlan and Peyton Roads. MSS 1011, Harry G. Lefevre Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The barricade was installed after Dr. Clinton Warner, a Black surgeon, purchased a home on 20 acres of land in Cascade Heights. His relocation, wrote Allen in his memoir, “se[t] off a holocaust among the whites.” White protesters dumped trash on Dr. Warner’s lawn, left harassing messages on his office phone, and threatened to burn his house. They demanded that a “racial buffer” be erected to prevent any additional Black homebuyers from moving in and “intruding” on white blocks. This practice was colloquially known as “blockbusting.” A derogatory term, pro-segregationists coined “blockbusting” to describe the phenomenon of introducing Black and other minority homeowners to previously all-white neighborhoods in order to lower property values and incite white flight.

“If it’s block busting when a Negro buys a house that he needs and can afford, then block busting will just have to stay,” said Dr. C. Miles Smith, co-chair of the All-Citizens Committee and president of the Atlanta NAACP in a 1962 interview with the Atlanta Constitution.

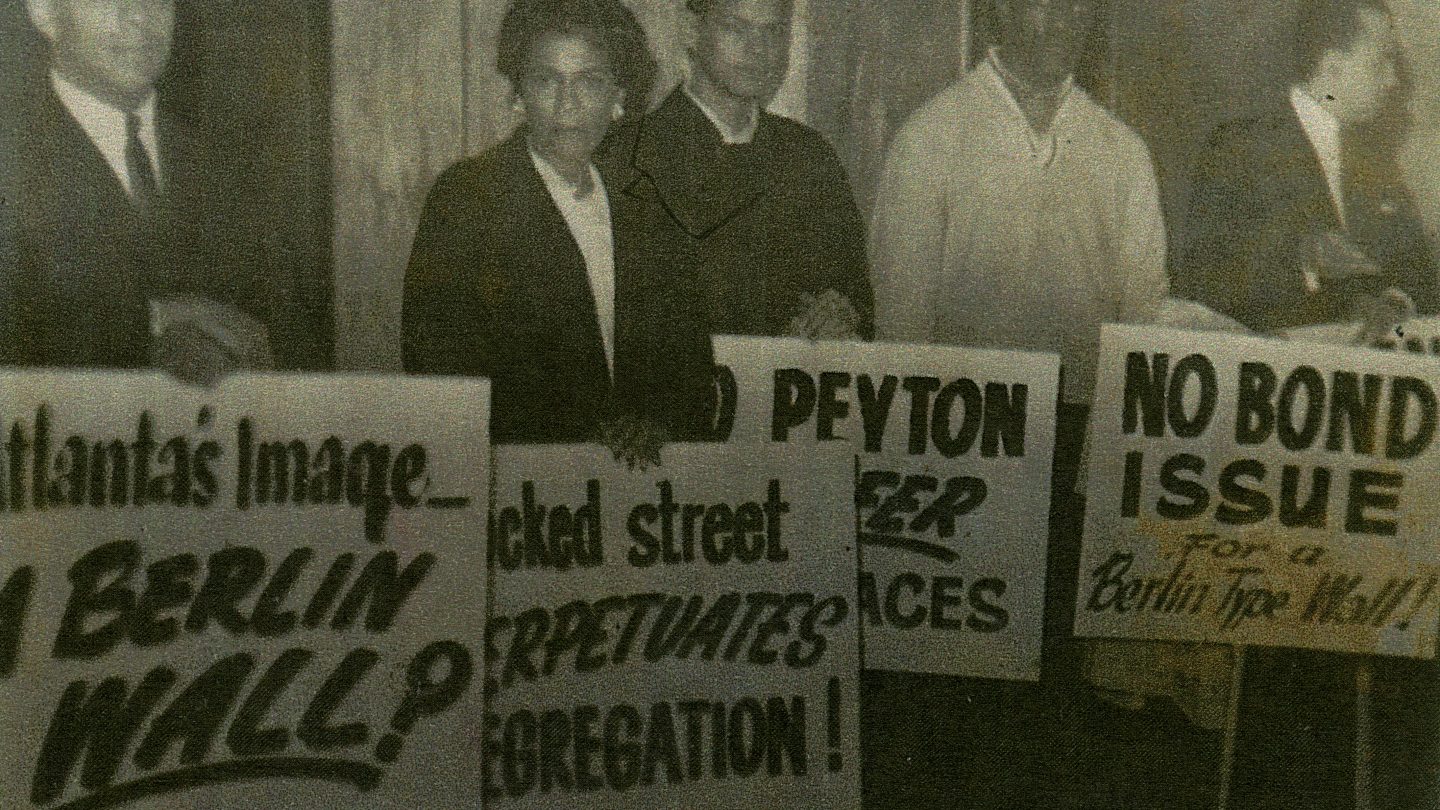

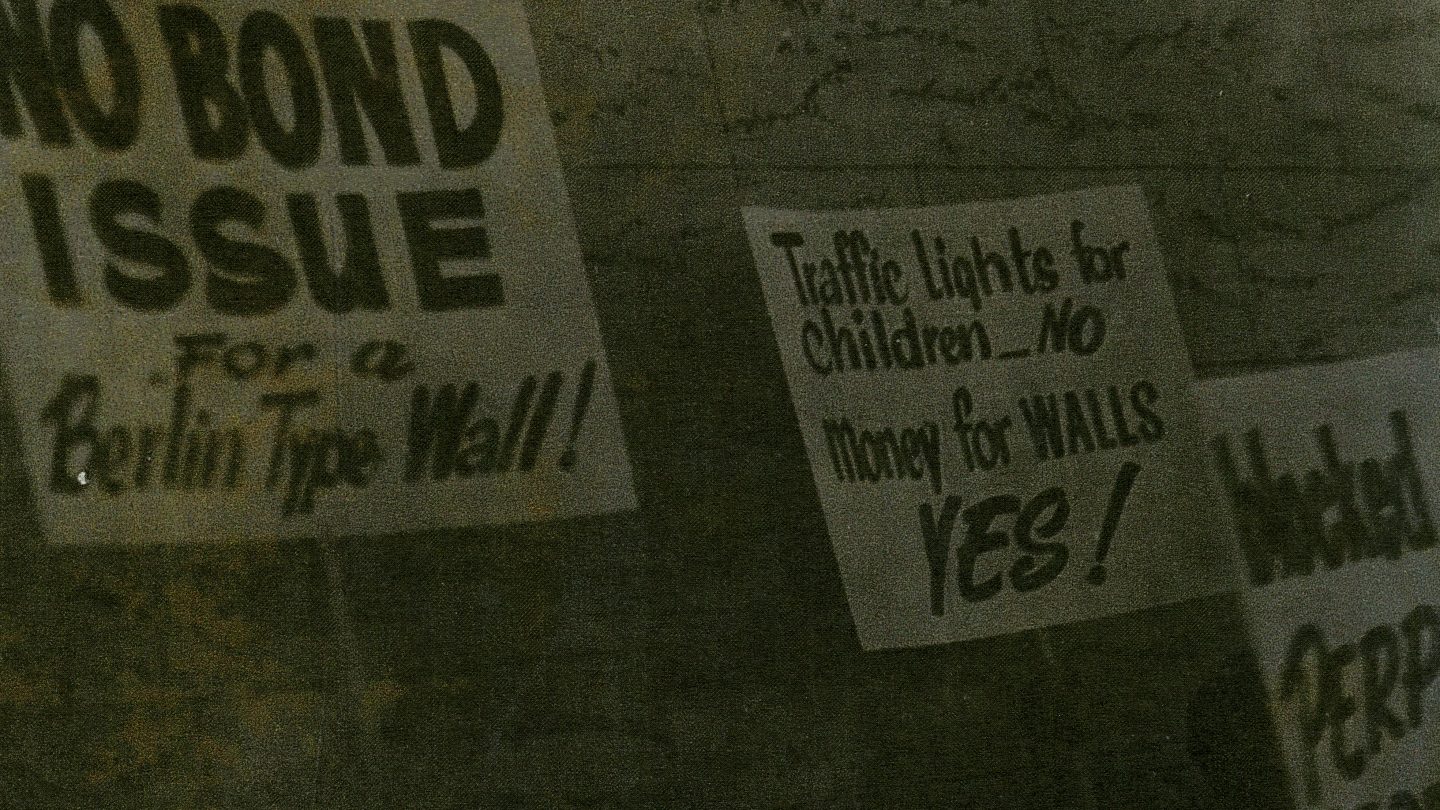

Hasty construction of the Peyton and Harlan Road barricades made front page news on December 19, 1962. via Newspapers.com

“I just needed a home, and it was an expensive home, and nobody else was there to buy it,” said Dr. Warner in a 2003 interview with the Atlanta Journal Constitution. He purchased the house for $60,000 (about $525,000 in 2021).

Allen, who beat out segregationist Lester Maddox for the mayor’s office in 1961, was caught in a public relations nightmare. He had secured victory due in large part to the Black vote, which he earned by campaigning on a pro-integration ticket. The longer the barricade remained up, the more tarnished Atlanta’s reputation became. As the story spread through national newspapers, protesters began to dub the project, “Atlanta’s Berlin Wall.”

Allen intended the wall to act as a passive solution to a race-based problem, hoping to further Atlanta’s image as “the city too busy to hate.” Ignoring the tension, however, instead of looking to resolve it head on led to increased strain. Following months of protest and legal contention from Black residents and with the eyes of America’s critics on the city, a judge ordered the barricade to come down. Mayor Allen had a demolition crew on the scene minutes after the ruling.

The Atlanta Wall stood for 72 days, but its effects are still being felt 50 years later.

By the late 1960s, Cascade Heights had become an affluent, predominantly African American neighborhood. White flight to the suburbs had begun in earnest and, by the 1970 census, Atlanta was a majority-black city. Mayor Allen came to consider the blockade an embarrassing mistake and a number of students used the episode as evidence of Atlanta’s poor race relations.