Skilled crafts like blacksmithing, woodworking, weaving, and pottery were all necessary for life in north Georgia. During the nineteenth century, much of that work was done by enslaved people. In some instances, these were crafts that enslaved communities had been practicing and sharing for generations prior to enslavement. For some, these crafts were introduced to them and were the forced labor they performed while enslaved. What remains consistent is that these craft practices often grew to become an opportunity for self-expression, both before and after Emancipation. Over the centuries, Black craftsmanship has dominated southern craft and leaves a long legacy for future generations.

During our 2025 Juneteenth celebration, we shared stories of enslaved and freed people whose craft was a testament to their skill and artistry. Their craft impacted their communities and remains a source of inspiration and joy to those who view their work. Many still carry on the traditions started by these craftspeople and add to the rich tapestry of creativity and craftsmanship in the Black community.

As you explore more about these practices and the people who perfected them, keep in mind a few big ideas:

-

Craft as Skill

During the 19th century, enslaved and free Black artisans honed their skills in a variety of crafts. They labored as carpenters, blacksmiths, weavers, and potters, creating exceptional works of art. Often the contributions of enslaved craftspeople were ignored, and their work was wrongfully attributed to others, including to slaveholders. Today, however, we recognize the undeniable skill that these craftspeople developed. Many were pioneers in their field and their work stands as a testament to their talent.

-

Craft as Community

Craftspeople were often leaders in their communities. Due to the mobile nature of their work, enslaved craftspeople connected separate communities by sharing news and information. Following Emancipation, craftspeople formed the foundation of a community by providing the structures and funding needed for places like churches and schools. Crafts also served as a way for communities to come together and preserve their traditions. This shared experience and artistic expression has allowed unique cultures to maintain their identity to this day.

-

Craft as Agency

In the years prior to Emancipation, craftspeople experienced more mobility as the work they did required them to travel. This limited freedom of movement gave many the opportunity to resist enslavement in a variety of ways. They were able to infuse their work with their own ideas and perspectives that they could not otherwise express openly. Following Emancipation, skilled labor and craftsmanship gave freedmen important economic opportunity. During Reconstruction and into the 20th century, these craftspeople would leverage their skills to create financial stability and political influence.

-

Craft as Creation & Joy

Craftspeople are artists who express themselves through the creation of functional pieces. These works of art take many forms: a pot, chair, quilt, or even a set of hand-forged tools. Craft can bring joy to the lives of those that use these unique pieces. Even more central to craft is the satisfaction the maker experiences in bringing an idea to life through his or her own skill and dedication.

Blacksmithing

A blacksmith is a craftsperson who works iron and steel, which is the origin of the name “blacksmith”; smiths of other metals would have similar names like goldsmith, silversmith, or coppersmith.

A blacksmith shop would not have been uncommon on a rural farm like the Smith Farm and the labor—called smithing—could have been done by enslaved individuals.

It was common for enslaved people to train in various crafts which would add to the farm’s self-sufficiency. Blacksmithing—and the related craft of farriering— maintained a working farm by repairing broken tools and providing shoes for horses or oxen that were used in the fields. Even wooden buildings and fences used nails made by the smith.

These enslaved blacksmiths also performed labor for neighboring farms that did not have a smith. Money earned from this labor would be collected by the slaveholder, although the blacksmiths sometimes retained a small amount of money to use for themselves. This, combined with the travel that would accompany their work, gave these smiths more independence and agency than most enslaved people.

Historic Blacksmiths

Gabriel Prosser

Gabriel Prosser was an enslaved man in Virgina born in 1776. During his life he did not use the surname Prosser, instead going by “Gabriel.” He worked as a blacksmith and, unlike many enslaved people, he learned to read and write. He often left the plantation where he was enslaved to perform work at other locations. This allowed him to organize the planned rebellion for which he is famous. Gabriel’s Rebellion was stopped before it ever fully matured due to leaked plans. Despite the rebellion’s failure, Gabriel’s story shows how the role of craftsperson gave blacksmiths greater agency to resist enslavement.

Solomon Williams

Some blacksmiths—like Solomon Williams—preserved traditional African metal working techniques. Williams was enslaved on a plantation in Louisiana where he labored as a blacksmith forging farm tools and architectural hardware for buildings. It is also said that Williams forged decorative grave makers for others on the plantation. He combined African and Christian symbols to create expressions and remembrances of the unique identities of those enslaved.

Tool made by Williams, National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Wilkes Flagg

The life of Wilkes Flagg, a blacksmith from Milledgeville, Georgia, shows how craftspeople also shaped their communities. Born in 1802, Flagg worked as an enslaved blacksmith until eventually living as a semi-freedman with his family in the 1830s. Flagg would eventually set up his own business as a smith and continue working into the 1870s. Following Emancipation, Flagg used his economic independence to support newly freedmen and established the Flagg Chapel Baptist Church, one of the first Black churches in his community. He also led efforts to establish a freedmen’s school in Milledgeville, which eventually became the Eddy School and helped educate the newly freed Black community.

Wilkes Flagg, James Bonner Collection, Georgia College Library Special Collections, Milledgeville, GA.

Woodworking

Wood was the primary building material throughout much of U.S. history. This includes both large structures, such as houses, as well as hand tools, furniture, and modes of transportation. At the Smith Farm, you can see relatively simple tools for turning large pieces of wood into smaller, more manageable sizes. Other tools of the time included chisels and hand planes used for more detailed work, such as making furniture. Like other skilled craftsmen who were enslaved, woodworkers were denied most—if not all—of the money they earned. Their labor was also sold for the profit of the people who enslaved them; this might include large construction projects, such as public buildings, railroads, or bridges. Like blacksmiths, woodworkers and carpenters would have been able to travel from project to project.

Historic Woodworkers

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey lived in South Carolina and labored as an enslaved carpenter until he won the lottery in 1799 and was able to buy his freedom. His wife, however, remained enslaved so he was unable to move away. Vesey set up his own carpentry shop in Charleston and was a successful business owner for several years. He was a leading member of his local church which would eventually become Mother Emanuel, one of the community’s earliest African Methodist Churches. With members of his church, Vesey organized a rebellion that was planned to take place in 1822 and brought together both freedmen and enslaved people. The plot was discovered before it could be enacted, and Vesey was executed for his contribution. During the Civil War, abolitionists used Vesey’s story to inspire Black soldiers like the U.S. Colored Troops. Stories like Vesey’s show how a craftsperson was a leader in organizing and uniting his community.

Denmark Vesey, National Park Service.

Thomas Day

Thomas Day was born a free man in 1801 to Black, landowning parents and worked as a carpenter in North Carolina. During his life he became a well-known and prolific craftsperson who created furniture renowned for its artistry. Woodworking and carpentry were crafts honed over generations by the Day family, with both Thomas’s father and brother also being cabinet makers. Day’s life was also complicated, as he himself used both free and enslaved labor in his cabinet shop. Day’s use of enslaved labor in his shop is a contentious point: some argue that it provided Day with cover for his abolitionist activities, while others hold it was purely for the economic benefit of free labor. Even with his undeniable skill as a woodworker, Thomas Day’s life proves complex and difficult in a generational story of craftsmanship.

Furniture exhibit in the North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA.

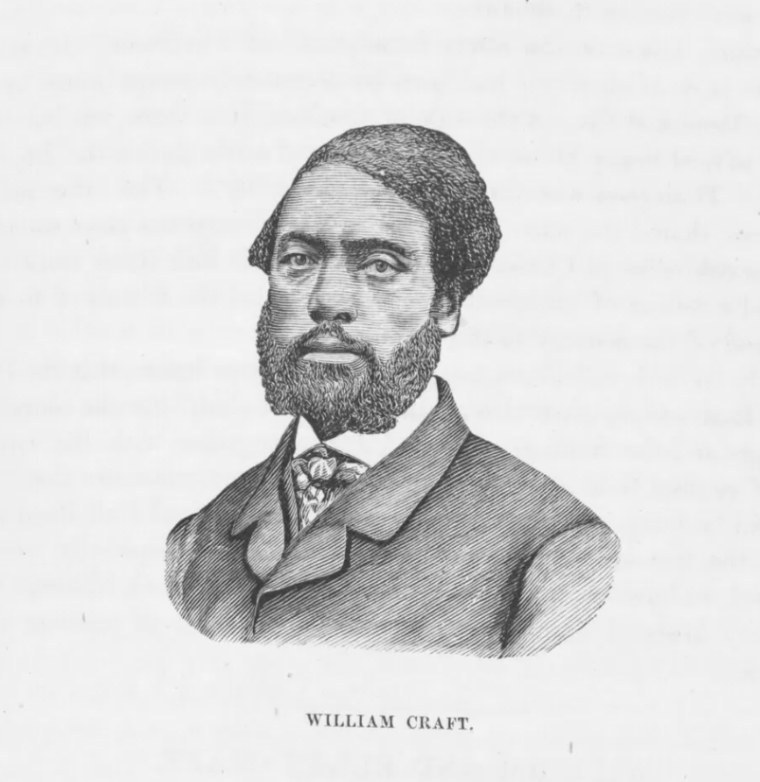

William Craft

William Craft was an enslaved carpenter from Macon, Georgia. Born in 1824, he escaped enslavement in 1848. Separated from his family at a young age, William was apprenticed as a cabinet maker. William and his wife, Ellen, devised an escape plan. Ellen disguised herself as a white man and William played the role of her enslaved servant. In their disguises, they escaped to Boston where they settled and opened a cabinet shop. Due to fugitive slave laws, the Crafts would eventually travel to England to remain free. In Europe, they traveled as abolitionists speaking out against the evils of the global slave trade. Following Emancipation, the Crafts returned to Georgia. The Crafts established the Woodville Co-operative Farm near Savannah to help educate newly emancipated freedmen.

Drawing of Craft from William Still’s The Underground Railroad.

Weaving, Quilting, and Basketry

Carding and spinning wool were important steps in creating textiles for use in weaving, knitting, and crocheting. Weaving on a loom—like the one inside the Smith House—would have been a common task for enslaved women on a farm or plantation. Weaving turned the wool from sheep or cotton harvested on the farm into a usable textile that was used for functional pieces or works of art. Woven or quilted textiles sometimes featured designs created by enslaved craftspeople and could be used to tell a story. Basket weaving was also a common craft in what is called the low country, or the coastal area of Georgia and South Carolina, that eventually grew into an art form.

Unfortunately, like so many Black craftspeople prior to Emancipation, many of these pieces are unattributed to an artist. Some continued their craft after Emancipation, however, and their work remains a powerful example of technical skill and imagination.

George Browne instructing students in the Penn Center basketry shop, Leigh Richmond Miner, c. 1920, courtesy of Penn School Collection, UNC Chapel Hill.

Historic Weavers

Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers was born into enslavement in 1837 but is well known for her work as a freewoman. A Clark County, Georgia native, Powers used quilting methods perfected for generations in the mountain South to create folk art. Powers used her skills as a quilter to continue the West African traditions of storytelling. Her 1885 Bible Quilt renders figures and scenes from the Bible into quilted cloth. Unlike other quilters, her pieces featured people and animals in a series of panels used to tell a story. She often depicted biblical narratives with the addition of naturalistic elements which can be seen in her 1895 Pictorial Quilt. Powers’ story shows how a craftsperson creates pieces that go beyond their function to be meaningful forms of artistic expression.

Harriet Powers in 1901, from Southern Quilting, via African American Registry.

Gullah and Geechee

A major craft in the coastal areas of southern states was basket weaving. For communities of enslaved peoples in the coastal regions of Georgia and South Carolina, it evolved from a practical need into a form of expression. Before the rise of cotton, these regions produced rice, and handmade baskets would have been used to separate the chaff from the grain of threshed rice. But as production of rice waned and cotton grew in popularity, the shapes of these baskets evolved, becoming the artform it is today. The Gullah and Geechee cultures are a unique people who once worked the early rice plantations along the southeastern coast of the United States. Because of the isolated nature of these regions, they maintained many of their West African traditions.

The Gullah and Geechee preserved and shared the creation of coiled baskets. Woven from a natural fiber called sweetgrass, these baskets show how the enslaved people of the coastal region combined their traditional methods with new materials. Despite less demand for baskets as rice production decreased, the Gullah and Geechee craftspeople continued to create these baskets to preserve their unique culture. Weavers now create baskets of all shapes and sizes, including three dimensional sculptures using the same weaving techniques and materials over centuries. These baskets are often sold as souvenirs, but they are each works of art that represent the shared history of a people. In this way, craft can be used to preserve a community, sharing history and culture from one generation to the next.

Pottery

Like all crafts, the art of pottery has a practical application. Its primary use was to make watertight vessels such as pots and pitchers. Enslaved communities had long pottery traditions that traced back to west Africa. Such pottery from the Bakongo, Wolof, Malinke, Sarakole, and Yoruba add artistic and spiritual aspects to otherwise functional pieces. Some of this pottery was used as ornamentation to protect graves and carried significant religious meaning. Enslaved communities adapted these traditions to the southeastern United States, creating a new type of folk art. An example of this is the style of jug called a face vessel which, as the name suggests, has large, exaggerated faces molded into the side of plain water jugs. These jugs possibly trace back to totems like the Bakongo’s nkisi which are visually similar and were thought to provide spiritual and physical protection.

Historic Potters

David Drake

Craftspeople working as potters were often not as mobile as woodworkers or smiths because they had stationary shops with kilns for firing their work. However, that does not mean their work was any less impactful. An example of the impact and influence a potter made through his work is the story of David Drake, also known as Dave the Potter. By doing something as simple as signing his name to his work, he showed a powerful act of resistance to enslavement.

As an enslaved person, Drake was one of many potters working in Edgefield, South Carolina. This area had large clay deposits that facilitated industrial-scale pottery and ceramics production. Like all the potters in Edgefield, Drake made alkaline-glazed stoneware jars, jugs, pots, cups, and pitchers that were used on many plantations throughout South Carolina and other southern states. So many of the potters who labored in this region remain unknown, however, Drake is remembered today because he signed his pieces as “Dave.” He even inscribed poems into some of his pieces. Most of Drake’s pieces are very large water or food storage vessels which provided a good canvas for his poetry. This writing is significant because of strict anti-literacy laws which restricted enslaved people’s ability to read and write during this time. Drake defied these laws and left a lasting mark on history with his work.

The jar pictured here is one of David Drake’s pieces, inscribed “Feb 11 1832 Dave.” It is currently on display in the Atlanta History Center Atrium for viewing.

By sharing these historic crafts and important stories, it is evident that Black craftspeople deeply impacted the function and artistry of craft through their dedicated skill, desire for agency, care for their community, and joy in creating. They have been technical leaders in their trade, creating wondrous works of art. By exercising their craft, they also used their agency to resist enslavement. They organized their communities both before and after Emancipation, building schools and churches that continued to educate and influence generations to come. Through the act of creating, they expressed their thoughts, feelings, and hopes, bringing deeper understanding and joy to themselves and those around them. The legacy of Black craftspeople endures through their work and continues to inspire us today.