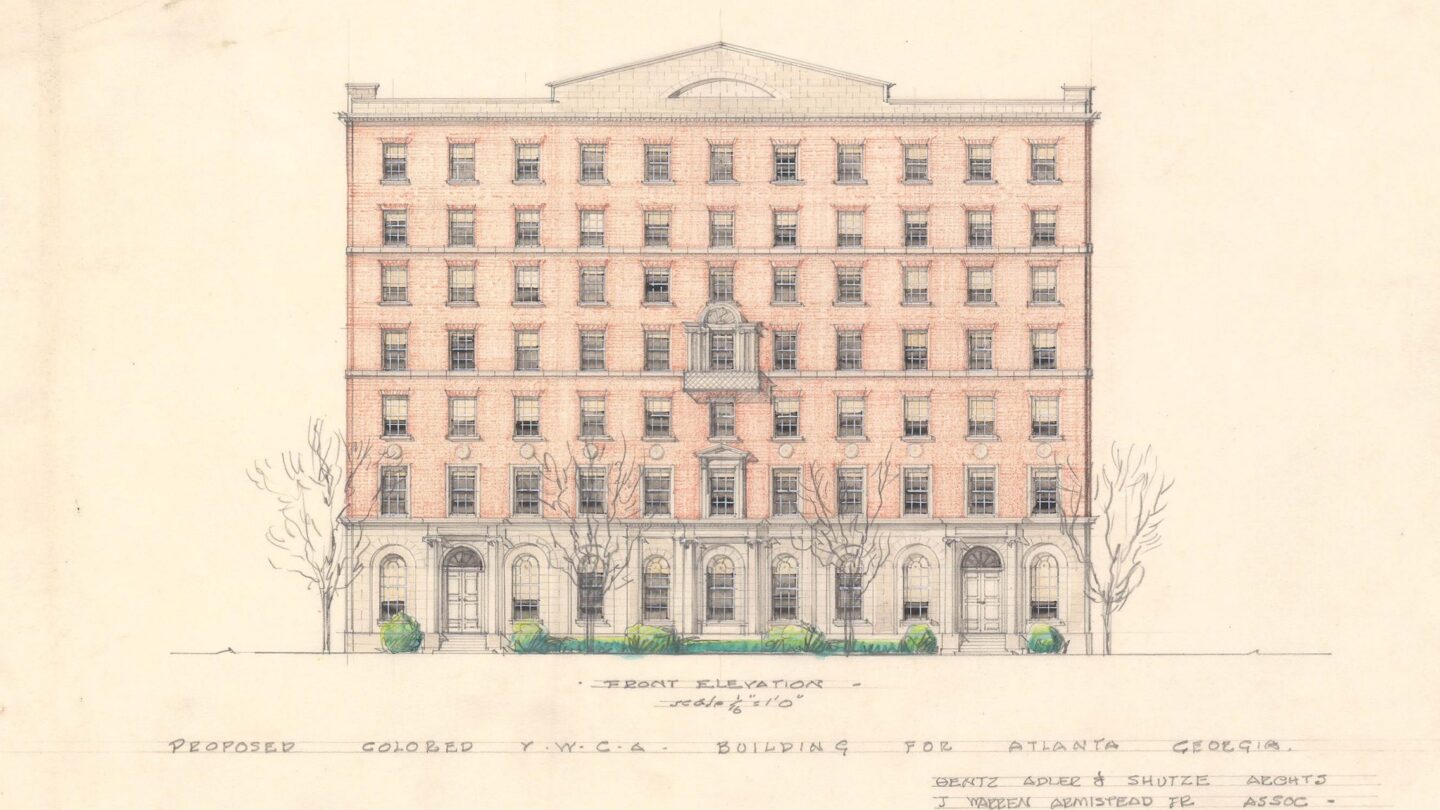

Facade of the Phyllis Wheatley Building for the Colored YWCA

One of our largest archival collections is now available to browse online. The Philip Trammell Shutze Architectural drawings collection comprises 638 sets of architectural drawings, 497 of which are digitized and available on our digital database. It’s part of a suite of materials owned by Atlanta’s famed architect that are housed at Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, including his Decorative Arts Collection, comprising ceramics, fine art, furniture, and architecture books. Parts of the Decorative Arts collection can be seen in our exhibition, Mandarin Shutze: A Chinese Export Life, on display at Atlanta History Center.

Our institution’s connection to Shutze runs deep. Not only did he donate the majority of his personal effects to the History Center after his death in 1982, he was also the architect of Swan House, the picturesque mansion that sits at the heart of our 33-acre campus—the drawings for which can now be accessed online for free.

Who was Philip Trammell Shutze?

Philip Trammell Shutze (pronounced Shut-zee) was known as the architect of Atlanta’s Jazz Age. Born in 1890, Shutze was a graduate of both the Georgia Tech and Columbia University architecture programs. A prolific designer, Shutze joined the architectural firm Hentz, Reid & Adler as a draftsman after returning to Atlanta from his studies in New York.

In 1915, Shutze won the prestigious Rome Prize for architecture and spent the next five years immersed in study at the American Academy in Rome. Despite the escalation and chaos of the first world war, Shutze found inspiration in the villas and city architecture of Italy. He travelled extensively during his time abroad. Rome afforded Shutze a practical, first-hand exposure to classicism—a style fundamentally different from the Beaux-Arts model on which he trained at Georgia Tech and Columbia. Of particular note to Shutze was the effect of time on the classical lines and textures of Italy’s landscapes. He found beauty in weather-worn facades and began to develop methods of aging a newly constructed building to more closely match its historical counterparts.

Upon his return to the United States, Shutze worked with architectural firms, including F. Burrall Hoffman Jr. and Matt Schmidt of New York. In Atlanta, he rejoined Hentz, Reid & Adler where he became a partner in 1927 after Reid’s death. The firm’s name became Hentz, Adler & Shutze, and later Shutze, Armistead & Adler until Adler’s death. The partnership of Shutze & Armistead continued until 1950. Although Shutze officially retired in 1958, he held an architectural license until 1980.

What can this collection teach us?

This collection (VIS 351) comprises architectural drawings from Shutze’s work within his various firms, including Swan House owned by Edward and Emily Inman; Goodrum House owned by May Patterson Goodrum-Abreu; Academy of Medicine at Emory University; Citizens & Southern National Bank; and The Temple, originally founded as the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation.

By studying this collection and the sketches of historically and architecturally important structures inside, we gain an understanding of how our city’s landscape changed over time while also forming a clearer picture of 20th century architectural styles. While researchers can use this collection to explore the history of extant structures, they can also find sketches of buildings that no longer stand. (Examples of which include the Atlanta Athletics Club on Carnegie Way.) This direct link with the inaccessible, physical past is the groundwork from which today’s historic preservationists learn to navigate challenges.

On a more basic level, this collection can help architecture students and others interested in the history of Atlanta’s urban landscapes learn more about a major architectural style (Classicism) that appears across various neighborhoods in the city.

As a whole, the collection gives us an impression of Shutze’s arc over time. It allows us to follow the ways in which his design shifted and evolved as his career progressed. It also gives insight into the technological advances of the day—what new building materials and techniques were used, how were modern elements incorporated into classical homes. It also gives us an impression of the economic climate. When Shutze began his career, he was designing palatial homes for wealthy families in the 1920s. With the crash of the stock market and onset of the Depression, Shutze turned his attention to commercial commissions from businesses on a budget.

Shutze’s unique flair is prominent in many parts of the city that have experienced exponential change over time. His versatility is on display in this collection—spanning elaborate private residences to public school buildings to commercial spaces. These drawings provide an in-depth view into the care and intentionality that goes into designing this array of public and private spaces.

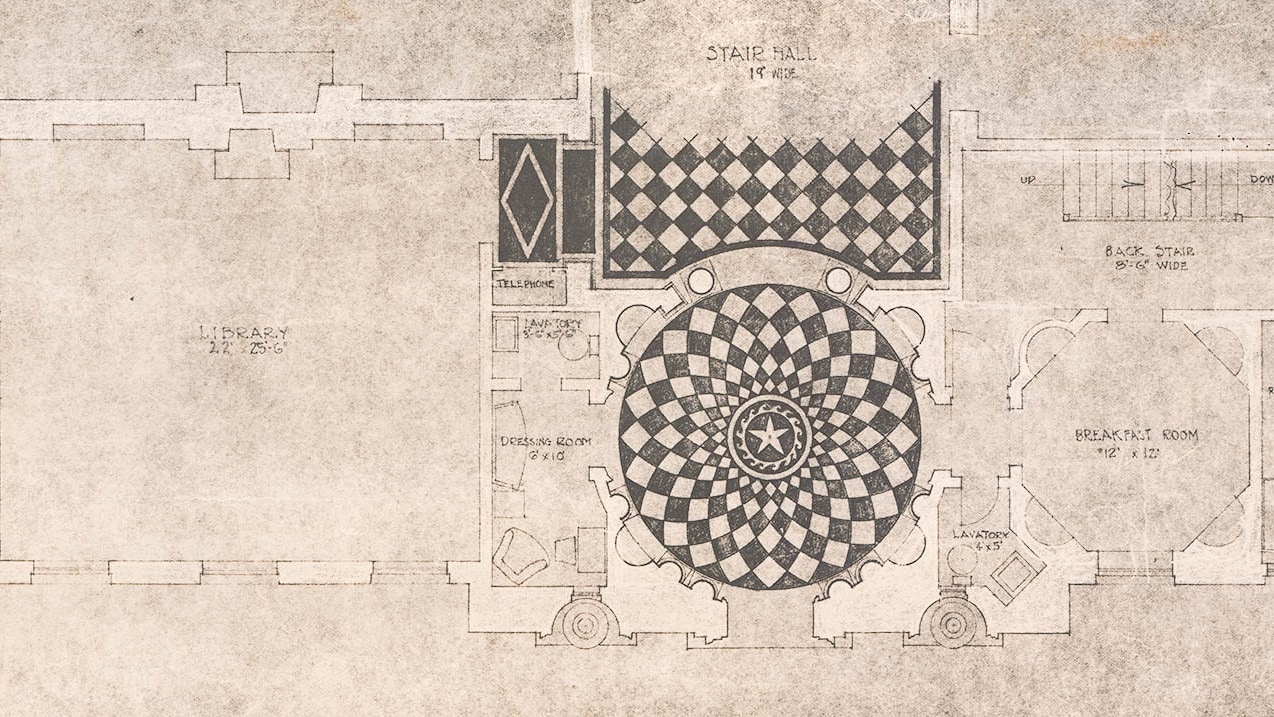

Detail of interior specifications for the Edward H Inman Residence (Swan House)

Private Homes

As in Shutze’s design for Swan House, we can see his incorporation of modern technology into classical design. In this sketch of the entrance foyer, we can see the placement of a telephone vestibule, designed to fit seamlessly into the existing design.

Sketches of the stairs show hidden steel structures, affording the grand staircase the illusion of floating in space.

Detail from the plan for residence of Donald S. McClain

Interior plans can also highlight the social strata of the era. In many of Shutze’s homes, such as the Donald S. McClain house, space is designated for owners and for staff. In the above drawing, we can observe what is pulled into orbit by the era’s social gravity: the children’s playroom, kitchen, pantry, and laundry are adjacent up to spaces used by the house’s staff. The spaces for homeowners and guests—dining room, library, porch, living room, etc.—are used for leisure and entertaining.

If you were to map the “served” and “servant” spaces in this sketch, you would find the “served” spaces at the front of the house, and the “servant” spaces at the rear, opening up to the garage at the back of the property. In this way, the collection provides insight into the interactions between staff (who often lived on the property) and homeowners.

Detail of the Davidson County Public Building and Courthouse

Schools and Other Public Buildings

The interior specifications can also shed light on the political context of the period in which they were designed. Some of the drawings in the collection show segregated spaces, such as the Davidson County Public Building and Courthouse in Tennessee. In the drawing, two separate floors are designated for “white men prisoners” and “colored men prisoners.” The women’s space occupies a single, segregated floor for “white woman prisoners” and “colored woman prisoners.”

Though images of separate water fountains and partitioned buses are common in history classrooms, the study of Jim Crow’s impact on architectural design is rare. This collection provides vital insight on the impact segregation had on the spatial systems of our built environment.

Detail of the Phyllis Wheatley Building for the Colored YWCA interior

The collection also contains sketches for the Phyllis Wheatley Building for the Colored YWCA located at the corner of Auburn and Piedmont Avenues. Built in 1940, this structure is an example of a “Black space” created as a result of the partitioning of segregation. By designing “whites only” spaces, architects (including Shutze) and their clients indirectly influenced the creation of Black spaces. This exclusion manifested across a number of public and private facilities like schools, parks, and recreational halls. Although signs were sometimes used to designate spaces for the exclusive use of whites, much of the time white space was commonly recognized and acknowledged by both races, rendering signage unnecessary. It was understood that the medical university or the bank were inaccessible to non-whites.

For this reason, the inclusion of the Wheatley YWCA building is unique—because it is an in-depth look at a Black space intended to provide shelter and a healthy education to its community.

In this way, the Shutze Architectural Drawings collection can help us more fully comprehend the day-to-day experience of segregation, particularly from the perspective of African Americans in Georgia and surrounding states.

Facade of Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company

Commercial Spaces

This collection also helps historians and researchers see how a site’s original occupant used the space, or how spaces were altered to accommodate new owners and uses. These drawings provide a roadmap to the ways in which needs and trends have physically altered the use of the structure.

Commercial spaces built in the 1930s and 1940s are indicative of an economic shift in Atlanta, as well. Shutze, who formerly designed lavish homes for wealthy families, now sought out commercial commissions. As is illustrated in the Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company, Shutze managed to retain his unique flair while paring back costly details. He also took into consideration the local architecture of a site, adapting his designs to better blend with the surrounding landscape. The Bell Telephone locations in Florida have a Spanish flair, while the Atlanta office retains more of his Classical roots.

Detail of Sears, Roebuck, & Co

In his later work (such as this Sears, Roebuck, & Company) Shutze adapted to meet the needs of his clients. While a modern department store is a far cry from Swan House, it retains his signature command of lines and textured surfaces. Just as Shutze’s style evolved, so did the city of Atlanta.

Why is digitization important?

The digitization of this collection is exciting for Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center in several ways. First, and most immediately, it lowers the barrier of entry for researchers and the public who might not otherwise visit the Reading Room on our campus to view physical copies. In this time of social distancing and beyond, Atlanta History Center seeks to connect people, places, and history. Digitizing our collections allows our materials to come to you when you can’t come to us.

Second, it allows us to better preserve the physical copies while allowing greater access to them. We no longer need to worry about the exposure of excess wear-and-tear on this already fragile set of documents.

Perhaps most importantly, though, it helps us form a more complete picture of the past in order to build a better Atlanta for tomorrow.

We invite you to explore the Philip Trammell Shutze architectural drawings collection and uncover more of Atlanta’s architectural past. If you’d like to experience Shutze’s work in person after viewing it digitally, visit us at Swan House. If you’d like to know more about the collections at Kenan Research Center, or to schedule a visit to our reading room, you can do so by calling 404.814.4040 or emailing at reference@atlantahistorycenter.com.