Western honey bee, Apis mellifera, collecting pollen and nectar from rattlesnake master, Eryngium yuccifolium in the Entrance Gardens. Photo by Sarah Roberts.

Sweet as honey—with a bit of sting. Adaptable, but assertive and aggressive when need be. Hardworking and focused with a sense of adventure to match. These are the Queen Bees of Atlanta—or the honey bees of the History Center! Atlanta History Center is home to four honey bee colonies named after real-life women who created a lot of buzz in Atlanta—Selena Sloan Butler, Frances Newman, Shirley Franklin, and Coretta Scott King. In honey bee colonies, females are the workers. The same has been true for women throughout several points in Atlanta’s history.

The Original Queens

Selena Sloan Butler

Selena Sloan Butler created the National Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers Association in 1911. It was the first parent-teacher association for African Americans in the United States. By 1919, she formed a statewide parent-teacher association in Georgia. Butler’s efforts inspired President Herbert Hoover to appoint her to serve on his 1929 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection. She also co-founded the Spelman College Alumnae Association, organized the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the Atlanta YWCA, and organized the Red Cross’ first Black women’s chapter of “Gray Ladies” during World War II.

Frances Newman

Frances Newman was a novelist, translator, critic, book reviewer, and librarian offering a rare feminist voice during the early 1900s. She wrote with satire and stylistic experimentation while critically examining the difficulties faced by women in the American South. She wrote witty reviews for the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution, served as a librarian at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and wrote The Short Story’s Mutations—a collection of stories she translated from five languages that sold out in its first printing. Her best seller, The Hard-Boiled Virgin, explored taboo topics such as menstruation, birth control, and sexuality. Her novels often challenged the confining traditions of “southern womanhood” and fearlessly portrayed Atlanta’s privileged white society in the 1920s.

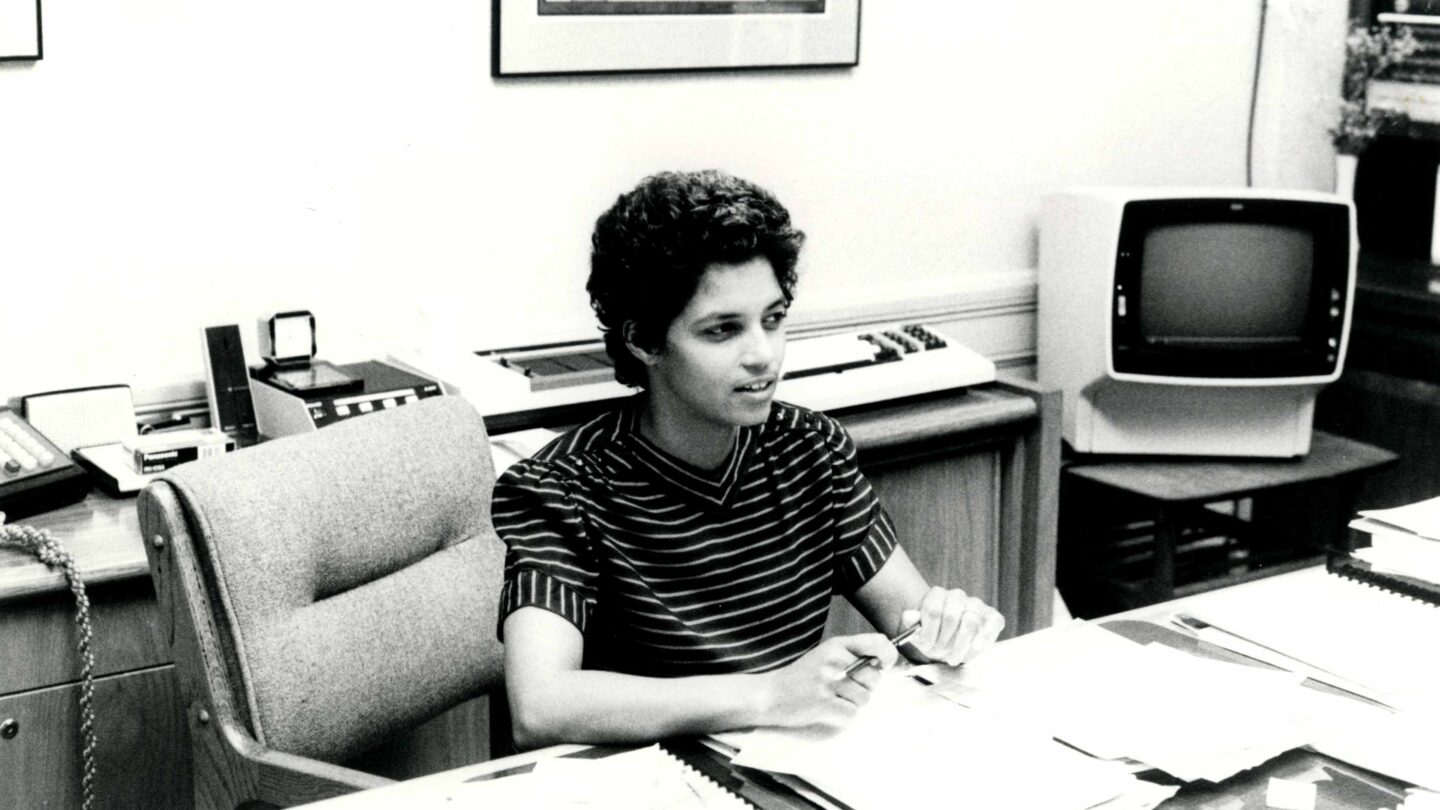

VIS 170.1575.001, Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center

Shirley Franklin

Shirley Franklin served as Atlanta’s 58th mayor from 2002 to 2010. She became the first woman to hold the post and the first Black woman to be elected mayor of a major Southern city. Earlier in her career, she was appointed as the nation’s first woman Chief Administrative Officer where she managed the daily operations of a city with nearly 8,000 employees. She was instrumental in developing Hartsfield International Airport, Centennial Olympic Park, a new city hall, a new municipal court building, and 14,000 net housing units. She joined the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) as a top-ranking female executive in 1991 and was named one of the five best big-city American mayors by Time Magazine in 2005.

VIS 158.01.134, Southline Press, Inc. Photographs, Kenan Research Center

Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King was an author, singer, activist, civil rights leader, and the wife of Martin Luther King, Jr. She was active in the Women’s Movement and spearheaded efforts to establish The King Center after her husband’s assassination. She successfully championed the process of having Dr. King’s birthday recognized as a national holiday—turning the most hated man in America into one of the most beloved. She was a long-time advocate for LGBT equality and world peace. King is widely considered one of the influential women leaders of the world.

VIS 101.473.003, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center

These women, much like our beloved honey bees, never shied away from doing the necessary work to ensure a better future for others.

The Queen Bees

The first Apis mellifera, or the western honey bee, made its North American debut in 1622. Two hundred thirty-one years would pass before they reached the west coast of our continent. This was due to disease, natural competitors, harsh climates, and geographical barriers—obstacles that prohibited the advancement of humans and honey bees alike at the time. Through traces of their impact on the environment, historical archaeologists have uncovered that honey bees, with their ecological benefits, helped influence the development of the United States.

Honey bees are beneficial for flowers, fruits, vegetables, and humans. Changes in plant species populations have been traced through pollen left in the soil and diaries and letters left behind by colonists and travelers. Furthermore, humans have used the honey bee and its products for cleanliness, diet, health benefits, and more for thousands of years. What is it that empowers honey bees to be such powerhouse pollinators? Proteins! Pollen is the only natural protein source for honey bees. During their busy season in spring, honey bees seek out plants to collect pollen and nectar. They transfer pollen between male and female parts of flowers, allowing plants to grow fruit and subsequent seeds. In turn, honey bees eat the pollen for strength and turn the nectar into one of the world’s most precious natural resources—honey.

Honey bee on Calamintha nepeta var. nepeta (calamint) in the Entrance Gardens of AHC

In urban areas and major cities like Atlanta, honey bees typically need supplemental feeding with mixtures of sugar and water when bees can’t find enough food on their own. There is a lack of supply and variety in plants carrying nectars which makes it harder for bees to meet their needs, especially at certain times of year. At winter’s arrival, honey bees live off everything they have stored, including their honey, and do not go out to seek any additional food.

But when your apiary sits on a 33-acre landscape including nine distinct gardens and diverse plant collections, your honey bee’s food supply is epic.

“We almost never have to supplementally feed. It’s once in a great while,” says Brett Bannor, certified beekeeper and Atlanta History Center’s Manager of Animal Collections.

“Normally, our bees don’t have any issues finding food with all the wonderful plants in their backyard. They can find food almost all the time—sometimes even on a warm day in December, whereas that’s not the case in a lot of urban settings.” Honey bees forage for food in groups and can generally create 2–3 times more honey than they need to ensure the colony’s survival and even reproduce itself. This abundance means that humans (and pooh bears) can enjoy the fruits of their labor, too. While they are generous to share their resources for the greater good of the ecosystem, honey bees are not happy when they are inconsiderately disturbed or threatened. Still, Bannor likes to peek in from time to time to make sure they’re happy at home.

Small hive beetles, Aethina tumida, are a persistent pest in our colonies. Here, Brett checks a trap that ensnares the beetles without harming the honey bees so they can do their jobs more efficiently. Just like with all of our living collections, we adopt the philosophy and practice of integrated pest management when working with our bees.

“Usually, I’ll just go out there and stick my ear next to the side of the colony and I’ll hear them buzzing. I only go in when absolutely necessary because if you disturb them, then they’ve expended more energy, causing them to eat more, which is not a good thing.”

It’s a unique job—for both honey bees and Bannor, who benefits from the guidance of Georgia Master Craftsman Beekeeper Cindy Hodges.

“It’s rewarding taking care of the bees, but I do like our heritage breed sheep a little better because I can snuggle with sheep, and they won’t sting me,” Bannor jokes. “Their temperaments are a little different, you know. But they have plenty of food and make plenty of honey. That’s all it takes to make me happy.”

We think it’s safe to assume that the Queen Bees of Atlanta are happy, too.