Although it’s known as a sweeping novel of the Civil War, the Civil War does not make up the majority of Gone With the Wind’s plot. More than half of the novel talks place during Reconstruction, the period directly after the Civil War. In Gone With the Wind, Margaret Mitchell provides a great deal of background information on Reconstruction. Yet very little of her history holds up to today’s factual standards. However, it was acceptable to many scholars in her own time.

The contemporary scholars who most shaped Mitchell’s opinion of Reconstruction were members of the Dunning School. Not a formal institute or building, its advocates were part of a school of thought about the interpretation of Reconstruction. Established at Columbia University in the 1880s through the writings of William Archibald Dunning, a scholar from New Jersey, the Dunning School was one of the first academic groups in the country to study Reconstruction as an historic event.[1]

They were also some of the first scholars in the United States to study history the way that we do today – by analyzing primary sources and making arguments about them.[2] This makes the Dunningites (as they were known) very complicated. Because, despite the fact they were respected scholars who advanced their field, many of their arguments about Reconstruction were fundamentally flawed.

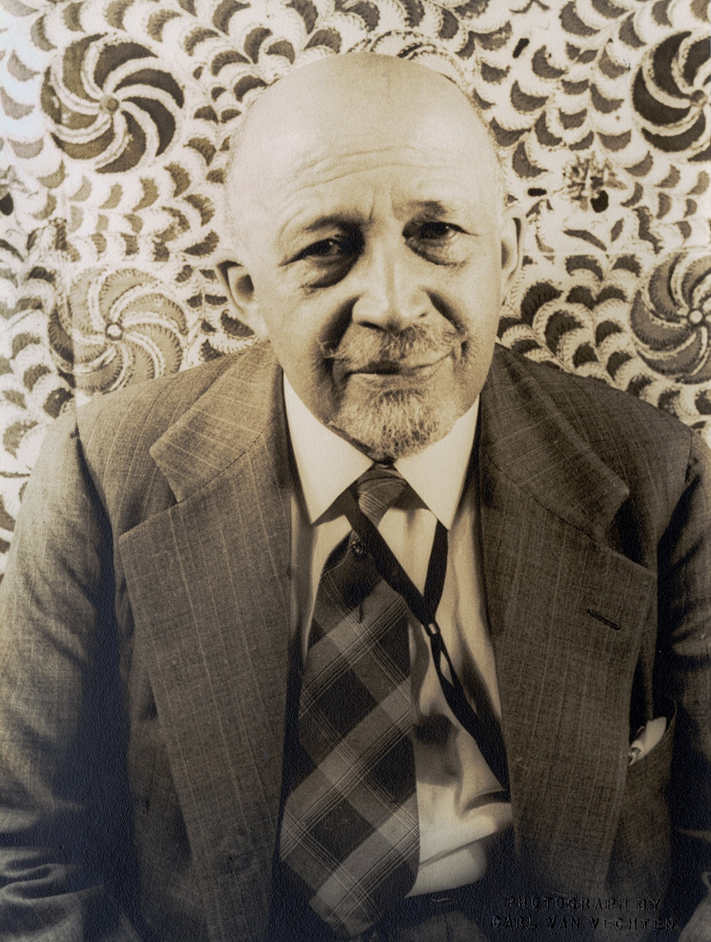

Dunning argued that the Civil War was fought over slavery, that the Confederate states seceded illegally, and that because of their role in starting such a destructive conflict, the states that were part of the Confederacy deserved to lose some privileges as they rejoined the United States government. Modern scholars still agree with these assessments. However, Dunning also argued that Reconstruction, the actual requirement of the Confederate states’ return to the US Congress, was a complete failure; primarily because of its policies giving political and civil rights to Black people.[3] Though modern historians refute this claim, very few people criticized Dunning’s work during his lifetime. The important exception was prominent Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, who first began to counter Dunning in 1901. Dunning, like most white Americans at his time, believed that Black Americans were incapable of handling such rights, and that in granting them those rights, the US government failed “inferior” Black people and unreasonably penalized white Southerners by forcing them to acknowledge their former slaves as equals before they were ready to do so.[4]

We know that Margaret Mitchell read and internalized the works of the Dunning School. She was a particularly big fan of Dunningite C. Mildred Thompson, who was also from Georgia and who was the only female member of the Dunning School. Thompson wrote to Mitchell to tell her how much she enjoyed Gone With the Wind – enough to name her new puppy after Scarlett O’Hara – and Mitchell wrote her back.

Thompson’s book, Reconstruction in Georgia, was, Mitchell said, her “mainstay” and “comfort” as she wrote Gone With the Wind (GWTW).[5]

Thompson sent Mitchell a copy of Reconstruction in Georgia after she heard what trouble Mitchell had finding one while researching GWTW.

Mitchell also owned other Dunning School histories of Reconstruction, including Claude Bowers’ The Tragic Era: Reconstruction After Lincoln.

Bowers’ book was a bit different from Thompson’s. He wasn’t writing for an academic audience; he was writing for the public. In his book, he took the most dramatic and least substantiated claims of the Dunningites and repackaged them for a mass audience.

Margaret Mitchell’s letters and her bookshelf indicate that she owned and read these books. But the evidence for her use of Thompson, Bowers, and others’ works doesn’t stop there. GWTW also clearly reflects them. Mitchell pulled closely from both Bowers and Thompson, weaving their ideas into her storytelling in GWTW.

Fooled by the Freedman’s Bureau? Attempts to Explain Freedpeople’s Politics

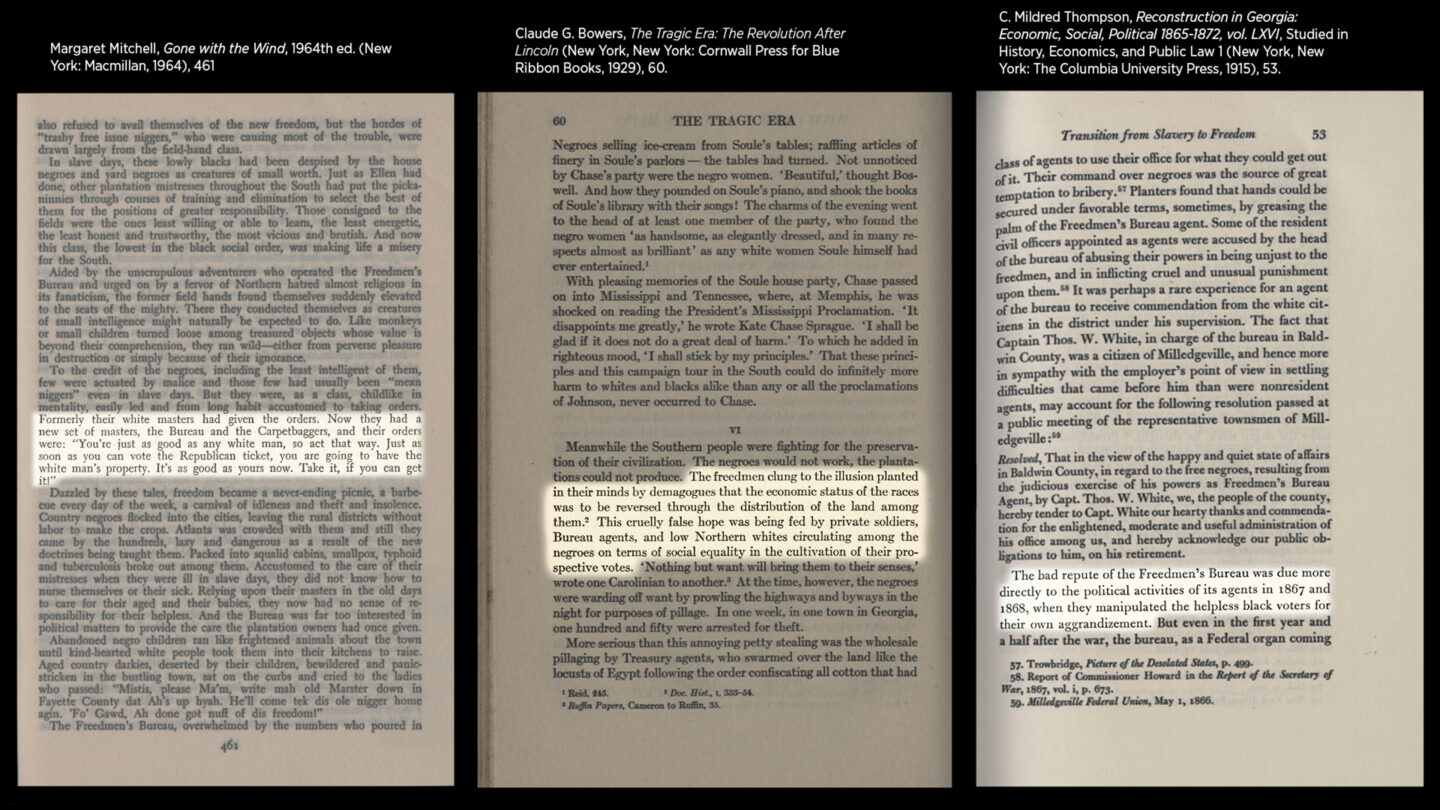

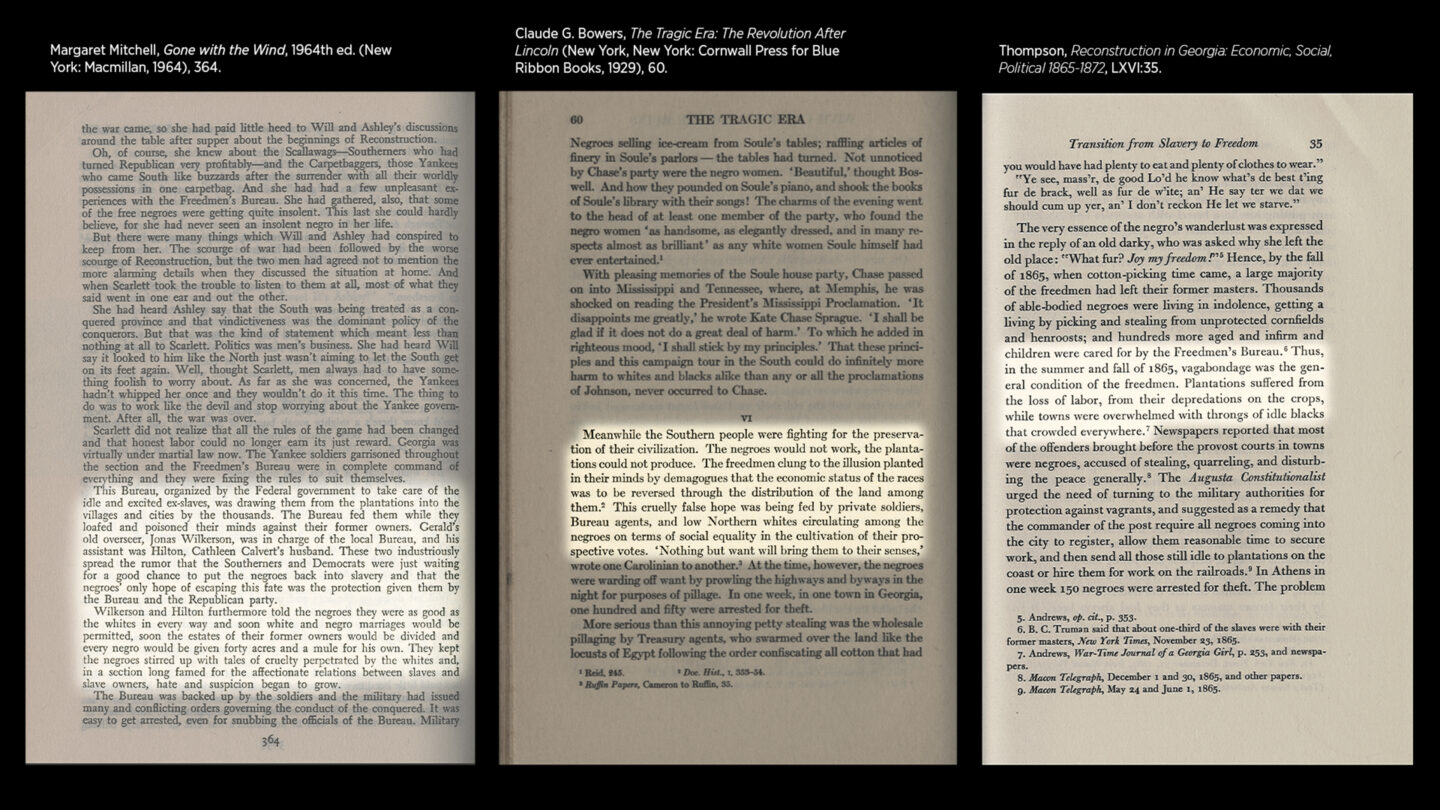

The idea, echoed in all three of these books, that Black people were being somehow tricked into voting for Republican candidates was a common one in Dunning School interpretations of Reconstruction. It played into the idea that Black people were incapable of political participation without being led by whites, and it served as an outlet for frustrated white southern Democrats attempting to explain why their former slaves wouldn’t vote for Democratic candidates. In reality, many Black people voted for the Republican Party because they realized Republicans were the party interested in advocating for them and their rights. In contrast, the Democratic Party was responsible for passing Black Codes while the party still held power in the South during the early days of Reconstruction in 1865 and 1866. Those codes often reflected the rules and restrictions of slavery.[6]

These quotes provide another example of the same false Dunning School arguments about the Freedmen’s Bureau and the recently emancipated. Jonas Wilkerson was a Freedmen’s Bureau agent in Gone With the Wind, and Hilton was a stereotypical “low [class] northern white.” Their roles in the novel demonstrate the influence of narratives such as Bowers’ in The Tragic Era on Margaret Mitchell.

Justifying the Ku Klux Klan: Blending Romanticism and Historical Inaccuracies

The idea that the crimes committed by the Ku Klux Klan across the South during Reconstruction were manufactured was used both to protect Klan members and to discredit Republican politicians in the South.[7] Many of the ‘outrages’ Georgia’s Governor Bullock brought to Congress, presented in all three of these books as false, really did take place. Governor Bullock was, in fact, chased out of Georgia after the December 1870 elections by the Ku Klux Klan, not because he was corrupt, but because he supported Republican politics and (to an extent) the political rights of Black men.[8]

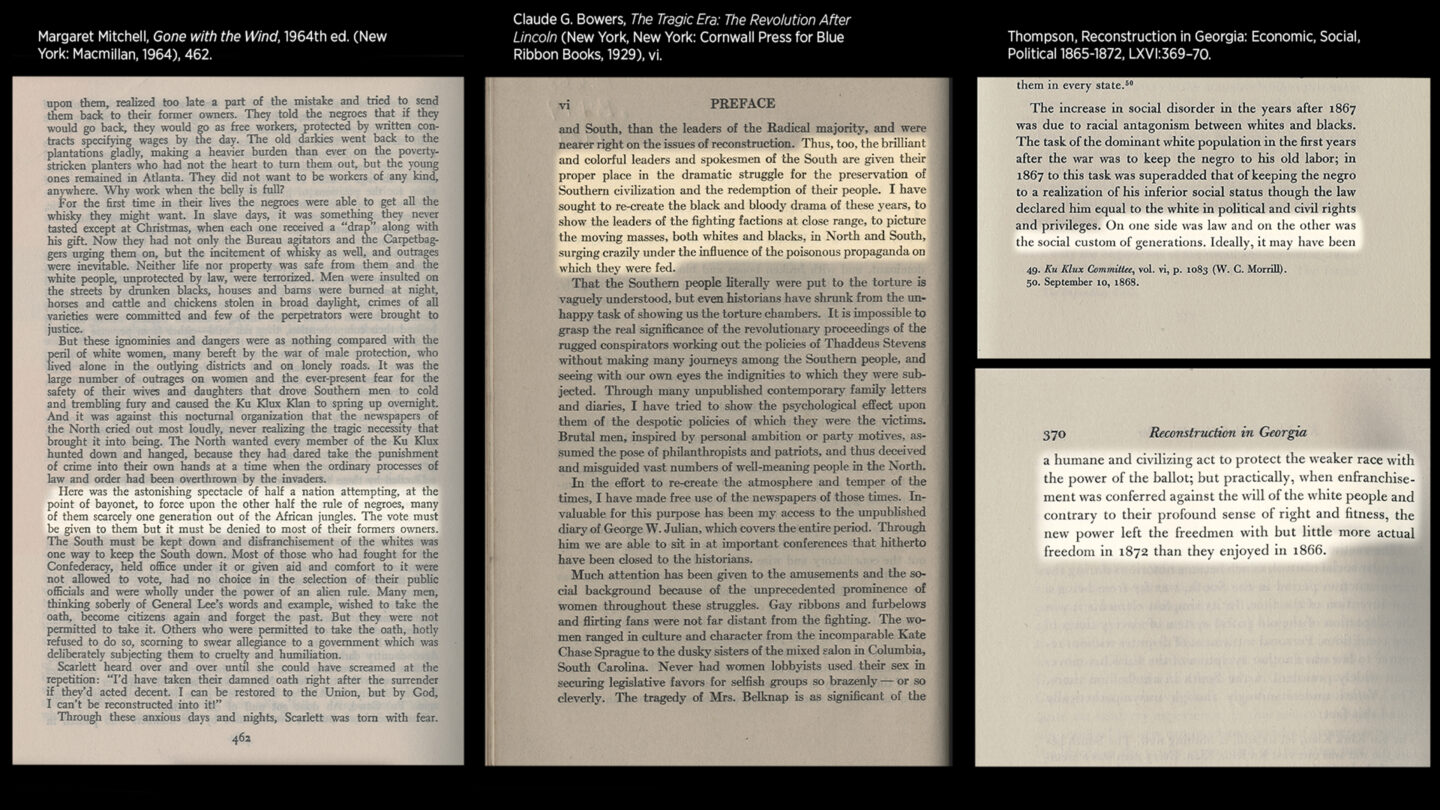

Melodrama and Reconstruction: Exaggerations to Justify Jim Crow

All three of these passages demonstrate the melodrama with which Reconstruction was portrayed by the Dunning School. In particular, these passages highlight the way that white southerners were portrayed as Reconstruction’s victims, fighting against brutal and unfair conditions. This is contrary to many modern interpretations of Reconstruction, which highlight the short time that white southerners who had just fought a war against the United States government were prevented from participating in that government and the enormous amount of work that was needed to even begin to bring Black southerners to a position of social and political equality with their white counterparts.[9]

Splitting From the Source Material: Margaret Mitchell’s Editorial Choices

Interestingly, though we know how much Margaret Mitchell respected C. Mildred Thompson and her work, there are several moments in Gone With the Wind that Mitchell chooses Bowers’ more melodramatic, less accurate interpretation in The Tragic Era over Thompson’s. For example:

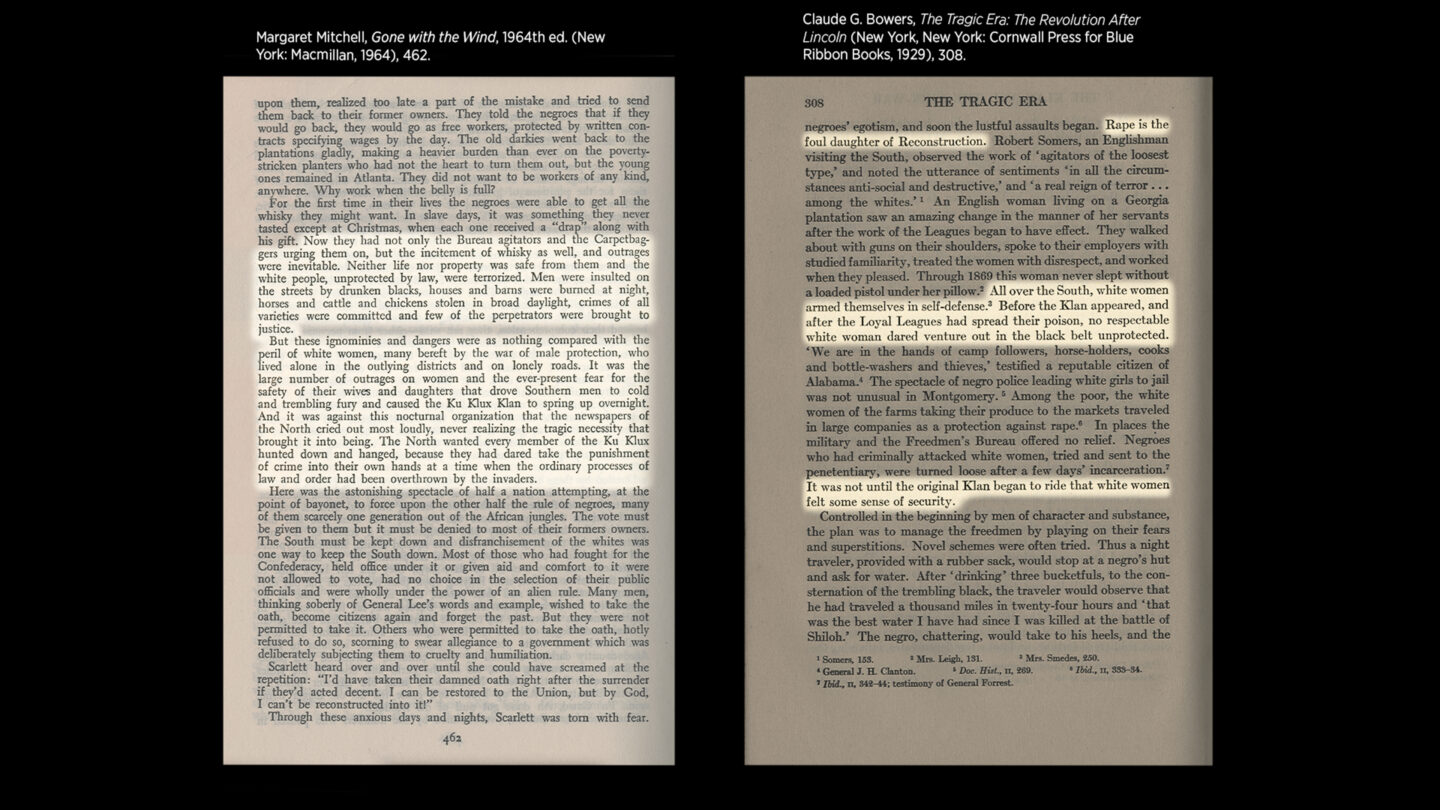

The version of the Ku Klux Klan presented by Mitchell and Bowers in this passage was designed to provoke sympathy for Klan members, and to justify the violence they carried out over the course of Reconstruction. It particularly misrepresents the reason the Ku Klux Klan was formed. Contrary to these stories, white women rarely faced sexual violence from Black men, and the Klan did not form to defend them because there was nothing to defend. Rather, it formed to intimidate Black people who attempted to practice their newly obtained civil and political rights, typically through extrajudicial violence that led historians to characterize the Klan as a terrorist group.

Though she showed sympathy for the Klan in line with her biased opinions about Black people, C. Mildred Thompson was aware of this fact, and clearly stated it in Reconstruction in Georgia.

It’s unclear what exactly motivated Mitchell to rely on Bowers over Thompson. Perhaps she used Bowers’ version of the Klan for dramatic effect, something she does discuss in letters to her publisher, Harold Latham of Macmillan, or perhaps Bowers’ work aligned better with the myths and misperceptions she’d grown up with.[10] Mitchell’s favorite book as a teenager was Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, which inspired The Birth of a Nation, a movie that was sympathetic enough to the Ku Klux Klan that it inspired the organization’s rebirth in the early twentieth century.[11]

Contradicting the Dunning School

The prominence of the Dunning School, and the fact that their work was published by a respected institution like Columbia University might make it seem as if Margaret Mitchell didn’t have much choice when it came to what kind of information she could get about the Civil War and Reconstruction. This is true to some extent. Her informational environment was very limited compared to ours, but that doesn’t mean she couldn’t access contradictory ideas.

Just four miles away from the Atlanta apartment where she wrote GWTW, nationally prominent Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois was writing his own book, Black Reconstruction in America. Du Bois published Black Reconstruction in 1935, the same year Mitchell gave her manuscript to the Macmillan Publishing Company. In Black Reconstruction, Du Bois argued that Reconstruction hadn’t been a total failure. He pointed out that most former Confederate states kept their Reconstruction-era constitutions, virtually unchanged from their original forms, and that Reconstruction was responsible for the establishment of valued programs such as public schools and hospitals in the South. When Reconstruction did fail, Du Bois wrote, it wasn’t because of the incapabilities of Black people. Rather, it was because prewar white elites did not want to lose the power they had held over Black people during slavery and were willing to use violence to regain that power. These white elites also wanted to ensure that the formerly enslaved couldn’t exercise the rights they had gained during Reconstruction.

Though he presented his research to other historians, including William A. Dunning, at conferences for decades, and published articles about it in The Atlantic and other prominent magazines, Du Bois’ work wasn’t accepted by the white academic mainstream until the 1960s. More moderate historians felt he was “taking sides” against white southerners in his work.[12] Others felt a bit more strongly. In response, Thomas Dixon, author of The Clansman and one of Margaret Mitchell’s literary idols, wrote a book called The Flaming Sword in which Du Bois was the central villain.

Today, Du Bois’ work still forms the basis of most historians’ interpretations of Reconstruction. He tried to approach Reconstruction from the lens that ‘the Negro in America and in general is an average and ordinary human being, who under a given environment develops like other human beings.” His approach is now much more respected than Dunning’s assumption of Black Americans’ inherent inferiority.

There’s no evidence that Margaret Mitchell ever read W.E.B. Du Bois’ work or that she would have had any desire to (outside of Thomas Dixon’s quotations of Du Bois in The Flaming Sword, which Mitchell told Dixon she was looking forward to reading), even if she was aware of who he was and what he stood for.[13] Even if Mitchell had wanted to read Black Reconstruction, it was published too late for her to incorporate it into Gone With the Wind. Du Bois’ work was not the only place, however, that Mitchell could get access to critiques of her Dunning School interpretation of Reconstruction.

Shortly after Mitchell submitted the manuscript that became Gone With the Wind to Macmillan Publishing company, Macmillan sent it to a test reader, Professor Charles Everett, who taught English at Columbia University. Professor Everett’s general assessment of Gone With the Wind was glowing. He thought it was an excellent novel that would sell many copies. But he did have concerns. For example, he thought “the author should keep out her own feelings in one or two places where she talks about negro rule.”[14]

Mitchell responded to Everett’s critique, writing, “He is absolutely right in that matter and I thank him for calling my attention to it. […] I have tried to keep out venom, bias, bitterness as much as possible. All the V,B&B in the book were to come through the eyes and head and tongues of the characters, as reactions from what they saw and heard and felt.” [15] Her response to Everett is interesting for two reasons. First, it hints she was aware that her portrayal of Black people during Reconstruction was biased or bitter, which are fundamental flaws of the Dunning School works she relied on. Second, Mitchell implies she is planning to change this content. The published version of Gone With the Wind includes many long passages in which the book’s omniscient narrator delivers significant pieces of information about Reconstruction that echo the Dunning School and its biases. It would seem that Mitchell either chose not to edit her Reconstruction passages, or that they were originally much more problematic.

Both Charles Everett’s critique and W.E.B. Du Bois’ book indicate something very important to bear in mind about Margaret Mitchell’s world when it comes to her responsibility for the historical content of Gone With the Wind. Mitchell and Du Bois were so close to one another physically when their books were published and yet, because Du Bois was part of Atlanta’s Black community, and Mitchell was part of its white community, their conceptions of the same historical even were completely different. Segregation hadn’t only changed the ways they went shopping or navigated public transit. It had also impacted the way they thought. The key difference was that Du Bois couldn’t ignore the Dunning School in his study of history. Mitchell and the Dunning School though, could easily ignore him.

Everett, as a white professor who taught at the same university as Dunning had, was a bit different. Mitchell saw his opinions as worth considering, but was not disturbed by his concerns about her portrayal of Reconstruction. They were minor critiques she found easy enough to respond to briefly or completely ignore. They did not upset her conception of her book as being historically accurate. To her, they were matters of opinion, rather than fact. This reveals the very different way that Reconstruction was understood in the early twentieth century and helps to explain the ways that the Dunning School pervaded not just in Gone With the Wind, but in American culture.

[1] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877 (New York, New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 110–11.

[2] Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877, 434.

[3] “Rufus Bullock,” New Georgia Encyclopedia (blog), accessed February 27, 2024, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/rufus-bullock-1834-1907/.

[4] Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877.

[5] Herbert Aptheker, The Literary Legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois (White Plains, New York: Kraus International Publications, 1989), 225–33.

[6] Mitchell, “October 3, 1938 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Thomas Dixon.”

[7] Mitchell, “July 27, 1935 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Harold Latham,” 27.

[8] Mitchell, 27.

[9] Margaret Mitchell, “July 27, 1935 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Harold Latham,” July 27, 1935, 27, Macmillan Company Records Author Files, New York Public Library Archives.

[10] Margaret Mitchell, “Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Thomas Dixon,” August 15, 1938, Margaret Mitchell Papers, Box 21, Folder 89, University of Georgia Special Collections; Margaret Mitchell, “October 3, 1938 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to Thomas Dixon,” October 3, 1938, 3, Margaret Mitchell Papers, Box 21, Folder 89, University of Georgia Special Collections.

[11] John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, eds., The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), 4.

[12] Smith and Lowery, 80–81.

[13] William Archibald Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction and Related Topics (Macmillan, 1897), 8, 13, 24, 178.

[14] Dunning, 176–77, 190-191, 252.

[15] Margaret Mitchell, “Feb. 9 Letter from Margaret Mitchell to C. Mildred Thompson,” February 9, 1937, Margaret Mitchell Papers, Box 84, Folder 33, University of Georgia Special Collections; C. Mildred Thompson, “Sept. 7 Letter from C. Mildred Thomspon To Margaret Mitchell,” September 30, 1937, C. Mildred Thompson Papers, Box 1, Folder 7, Kenan Research Center; C. Mildred Thompson, “Undated Letter from C. Mildred Thompson to Margaret Mitchell,” n.d., Margaret Mitchell Papers, Box 84, Folder 33, University of Georgia Special Collections.