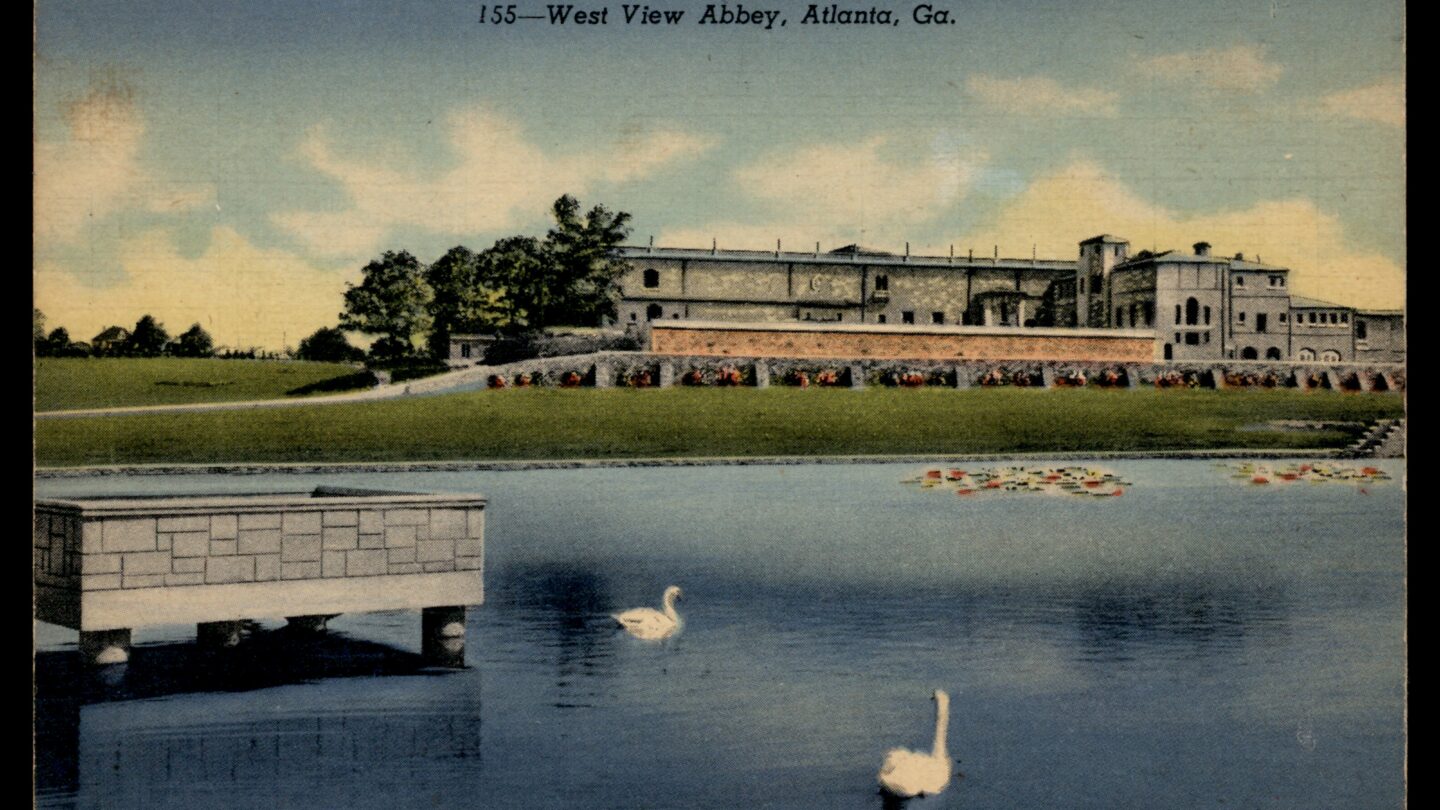

Westview Abbey, ca. 1950, Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Cemeteries are much more than places to bury and remember the dead. They’re ever-evolving records of how we think about death. Cemeteries reflect the culture and ideas of the people who built and are buried in them. This is certainly true of Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery which, in addition to serving as the burial place of thousands of Atlantans, including some of the city’s most influential citizens, echoes the history of the city of Atlanta in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Westview, fittingly located in western Atlanta, was established near the city’s West End neighborhood. Today, the neighborhood in which Westview was built is known as Westview thanks to the cemetery’s influence. At over 582 acres, Westview is the largest civilian cemetery in the Southern United States.1 In addition to serving as a final resting place for over 100,000 Atlantans, it has been the site of a Civil War battle, several gunfights, the discovery of at least one new species of plant, and a display-place for hunting trophies.2

A New City Cemetery

Before Westview became the iconic (and enormous) piece of Atlanta’s history that it is today, it was known as West View Cemetery, and it was the solution to a problem Atlanta was delighted to have: a growing population. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the city’s population boomed, going from 9,554 people in 1860 to 21,789 in 1870 to nearly 54,000 by 1880. Atlanta, in the words of official city historian Franklin Garrett, “came to resemble a medium-sized city rather than a fair-sized town.”3 But you wouldn’t know that from the city’s cemetery. Established in 1850 as the “City Cemetery” and renamed Oakland Cemetery in 1876, the only government-sponsored burial site in the city was full.4 There were no more burial plots to be sold, and it was large enough that its position in the center of the city was becoming a health concern. By the early 1880s it was clear that a city that was growing as much and as quickly as Atlanta was going to need a new place to bury its dead.

At first, the new cemetery was planned as a city enterprise, but Atlanta’s government eventually determined (as it often did with municipal services) that the cemetery would fare better as a private enterprise.5 A group of prominent Atlanta businessmen, led by Edgar Poe McBurney, and including such influential figures as Lemuel P. Grant, W.P. Inman, and former Georgia governor Rufus Bullock, quickly stepped up to take on the project. In May of 1884, McBurney and his partners applied to incorporate the West View Cemetery Association and immediately began looking for a tract of land on which to build a new cemetery for Atlanta.

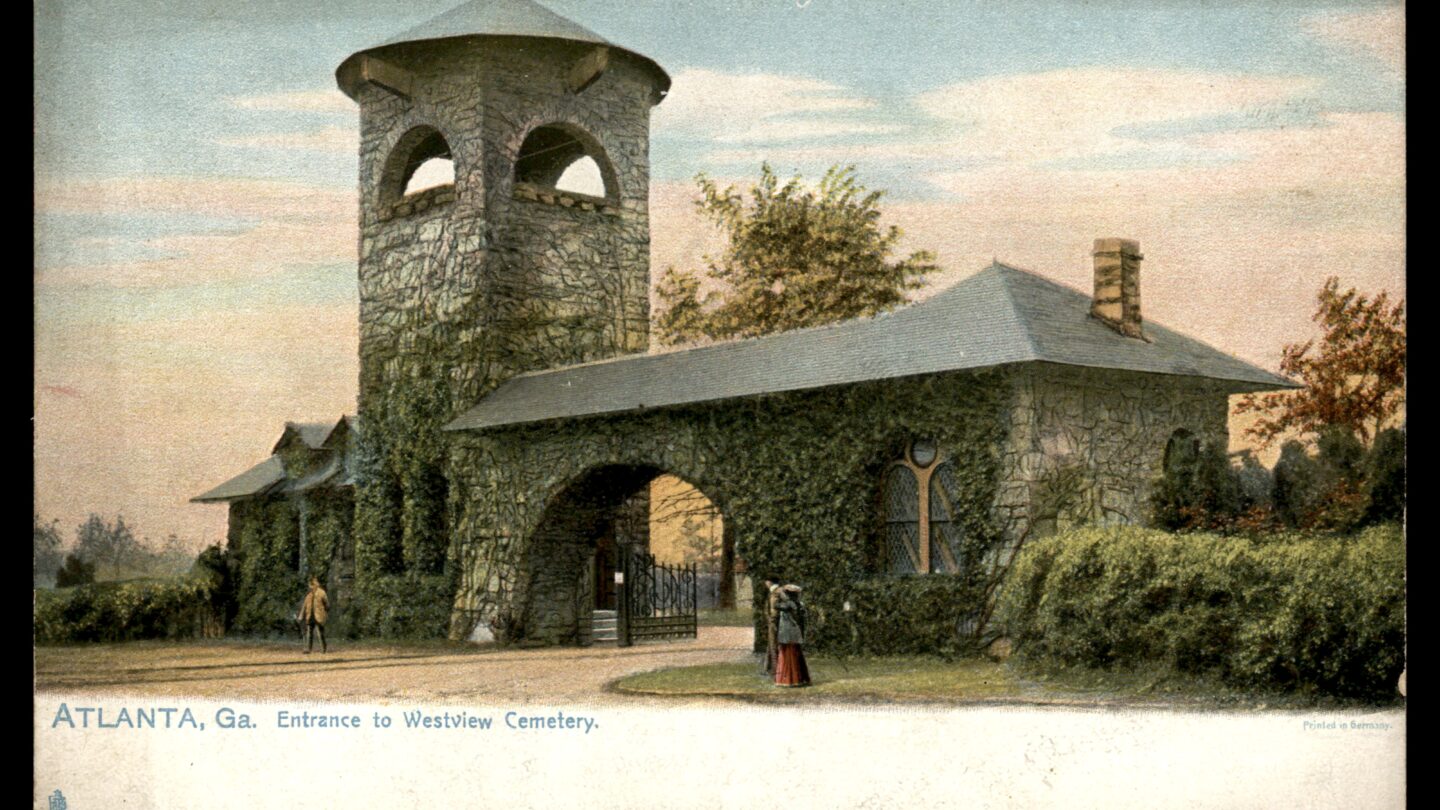

Their work paid off in the form of West View Cemetery, a 570-acre tract purchased, sometimes with difficulty, from landowners in West End, and intended to meet the burial needs of the whole city of Atlanta. The cemetery, which opened in August of 1884, had its first burial on October 9, 1884, when Mrs. C.R. Haskins, wife of the man who purchased one of the first lots sold at West View, was interred.6

The establishment of West View Cemetery in the 1880s reflects the history of Atlanta in the 1880s, both in terms of the city’s rapid population growth and its burgeoning and increasingly influential class of business leaders. It also reflects the broader culture of the 1880s United States and its beliefs about the dead. West View was designed with the newest trends in cemetery architecture in mind. Based on the recently established and highly popular Woodlawn cemetery in the Bronx, New York, West View was designed to be a lawn-park cemetery. Lawn-park cemeteries were intended to democratize and simplify earlier cemetery designs. These cemeteries would have expansive green spaces with limited, landscaped trees and shrubs, hidden outbuildings, and burial grounds organized largely around family monuments surrounded by smaller, individual headstones.7

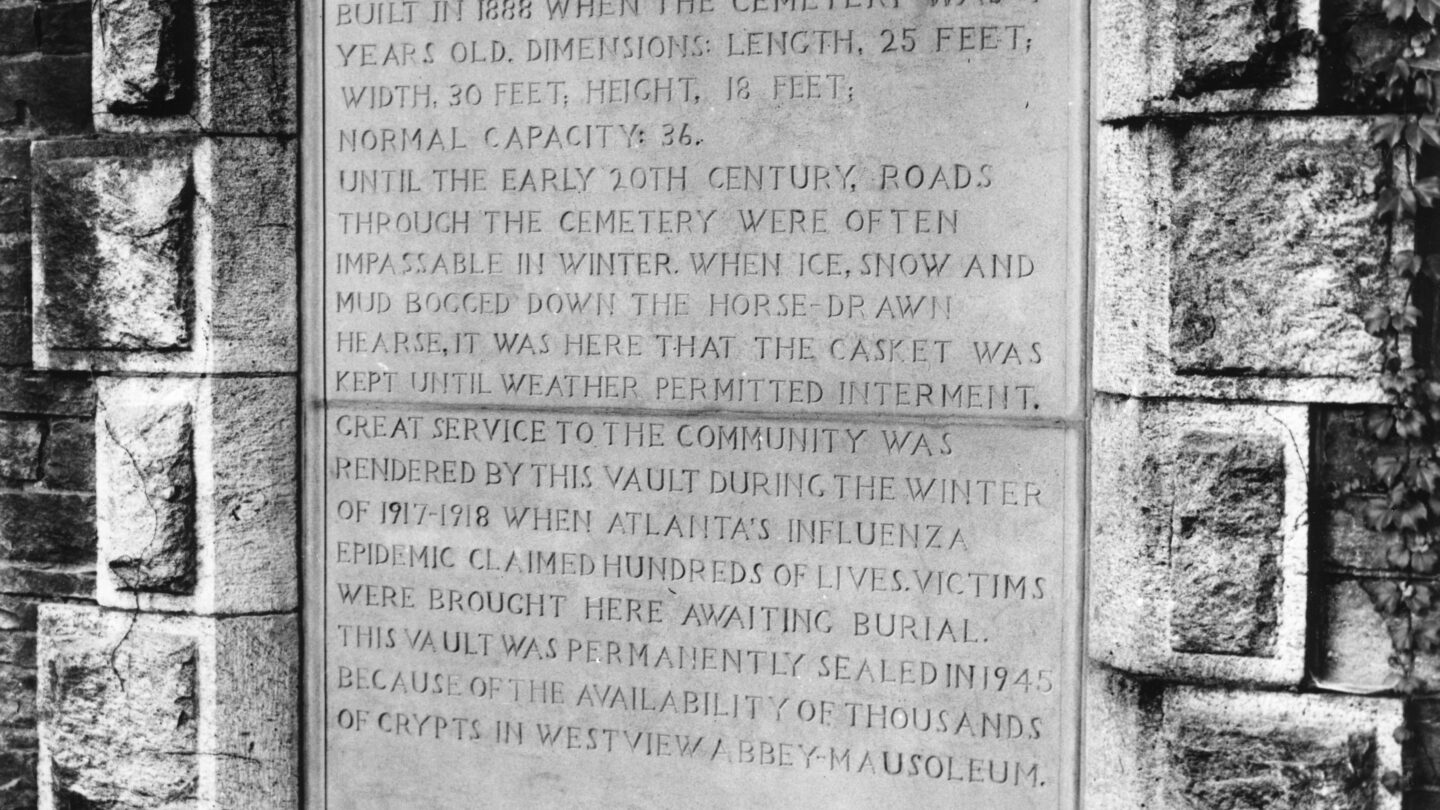

In an interview he gave to the Atlanta Constitution profiling the new cemetery and the Cemetery Association’s plans for its development, E.P. McBurney emphasized West View’s future plans for magnificent drives and avenues (it now has 19 miles worth) that would wind through the cemetery, water features and fountains that would later adorn the property, and a receiving vault. The vault, a once important but now largely defunct feature of cemetery architecture, allowed West View to preserve bodies until conditions were ideal for burial (i.e. waiting for the ground to thaw after a cold winter) or if families needed time to purchase a lot before burying their loved one.8

West View, McBurney said, was “a labor of love.” He and the other Cemetery Association members were working hard to “give Atlanta a cemetery that will be the admiration of visitors and the pride of our citizens.” As McBurney had hoped, West View took off quickly, helped both by the lack of available plots in Oakland and its own reputation as a beautiful place to bury someone. In its first five years, nearly 3,000 people were interred at West View Cemetery.9

Rest Haven and God’s Acre

West View was required by the city to provide burial spaces not just for the wealthy, white Atlantans who helped found it and who could afford to pay for plots, but for the whole city. The cemetery originally met this requirement with two different sections: Rest Haven and God’s Acre.

West View needed to provide Black Atlantans with somewhere to bury their dead. As an institution of the late-nineteenth-century South, it needed a segregated section in order to do so. The solution was Rest Haven.

Rest Haven only served its purpose for about two years. In 1886, Atlanta’s government finally granted Black Atlantans permission to start their own graveyard and, shortly thereafter, South-View cemetery was opened. As a cemetery whose goal was to provide Black Atlantans a place to bury their dead that did not subject them to the indignities of segregation, South-View took significant business from West View and Rest Haven, quickly rendering the segregated section if not obsolete, then noticeably unpopular with the population it was intended to serve.

God’s Acre served another city-required purpose for West View: the provision of burial ground for those who could not afford a funeral or a cemetery plot themselves. God’s Acre functioned much differently than the rest of West View. Rather than being buried in elaborate family plots signified by large central markers, those laid to rest in God’s Acre were buried in rows according to their date of death, and were only marginally segregated (individual rows, rather than entire sections of the plot were organized by race).10

As West View’s role in Atlanta changed, so too did the ways that God’s Acre and Rest Haven were used. In 1907, West View established its first perpetual care plan, a system that set aside funds from each purchased plot to help pay for its long-term maintenance. Even as family members died themselves or moved away, graves included in the perpetual care plan would have their grass mowed and shrubs trimmed. Neither God’s Acre nor Rest Haven were included in the 1907 perpetual care plan.

Rather than reflect the shifting tastes of people who had little control over where they were buried, the decision to exclude God’s Acre demonstrated West View’s shift from a cemetery partnered with a city to an entirely independent enterprise. After obtaining a less expensive contract with a different cemetery in 1925, the city of Atlanta stopped burying its poor and unidentified citizens at West View. The cemetery’s decision to leave out Rest Haven as well speaks both to the greater popularity of South-View Cemetery with Atlanta’s Black residents and to the influence of the Jim Crow South on Atlantans’ sense of how they ought to be buried.

West View and Civil War Memory

E.P. McBurney and the West View Cemetery Association had never intended for the cemetery to be home to family memorials and grave markers alone. Plans for elaborate fountains notwithstanding, they also wanted to commemorate the history of the cemetery’s grounds.

Almost twenty years to the day before West View cemetery opened, part of its land was the site of the Battle of Ezra Church, part of Union General William T. Sherman’s campaign to take the city of Atlanta during the Civil War. On July 28th, 1864, both Union and Confederate soldiers died in an engagement on the future site of the cemetery.11 When West View was established, it was still possible to see Confederate breastworks on the cemetery’s edges. (Breastworks can still be seen in two areas of Westview today).

McBurney and the Association had originally planned to “preserve [the breastworks] and to mark each fort with the name it had during the war.”12 Their plans, however, were changed, caught up in the broader debates about Civil War memory taking place in the United States in the late nineteenth century. The Lost Cause narrative, a collection of myths and misrepresentations of the history of the Civil War used to argue that the Confederacy had been justified in starting a war against the United States, that it had been fighting for states’ rights, rather than the institution of slavery, and that though the Confederacy lost the war, it was the moral victor in a contest against overwhelming Union numbers, was becoming more and more influential, particularly in the South.

Another narrative of the Civil War, closely tied to the influence of the Lost Cause, was also gaining popularity as West View came into being: Reconciliation. Reconciliationist narratives emphasized the idea that both Union and Confederate soldiers fought patriotically and honorably for their understanding of what the United States was supposed to be, often ignoring the realities of the war (the existence of Black Union veterans in particular) and why it was fought in favor of a story of an argument over Constitutional semantics between white brothers.

A rare clash between these two narratives came to a head at West View shortly after the cemetery opened. In 1885, an organization called the Battle Monument Association of the Blue and the Gray met with the West View Cemetery Association and began planning a monument to the soldiers who died in the Battle of Ezra Church to be erected in the cemetery.13 The Battle Monument Association was in an interesting position in the nineteenth-century South. Unlike most monuments being proposed to Civil War soldiers at the time, they suggested that West View’s pay tribute not only to Confederate soldiers who died in the battle, but to Union soldiers as well. The two associations began reinterring soldiers who had died at Ezra church in the dedicated plot the West View Cemetery Association had set aside but never finished the monument itself.14 In large part, they were slowed to stoppage by criticism of the planned monument. Though reconciliation was gaining ground as a narrative, many white Southerners bristled at the idea of honoring Union and Confederate soldiers equally in a Southern cemetery; they wanted West View’s monument to honor the Confederate dead exclusively.

As the efforts of the Battle Monument Association continued to stall, the West View Cemetery Association looked elsewhere for a sponsor for its Civil War monument. The Association went on to partner with an Atlanta Confederate veterans’ association to build an exclusively Confederate monument in 1888. This time, West View was more careful about its timeline – the veterans’ association was given two years to build their monument or lose their contract. By 1889, a monument to the Confederates who died at the Battle of Ezra Church and in the Civil War generally was erected in West View Cemetery, over the bodies of Confederate soldiers.

Image of the Confederate monument erected at Westview Cemetery, likely taken after 1939, when the United Daughters of the Confederacy started holding Confederate memorial day celebrations at Westview. Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

The End of an Era

After establishing West View Cemetery in the 1880s, E.P. McBurney went on to run the cemetery for nearly fifty years. During his tenure as head of West View, he oversaw its first burials, its evolution from a privately-run city cemetery to a fully private enterprise, the erection of many of the cemetery’s now-famous buildings, and the establishment of complimentary businesses (such as the West View Floral Company, which went on to become the largest greenhouse operator in the South) on the cemetery’s grounds.15 When McBurney retired from West View in 1930, the board sold the cemetery to a prominent family of Atlanta real estate investors who had first offered to purchase West View in 1927: the Adairs.

Brothers Frank and Forrest Adair managed West View for just three years and struggled to maintain the cemetery’s earlier success in the face of the economic turmoil of the Great Depression. By 1933, they were reporting net losses at West View and looking for a $565,000 loan (nearly $15 million today) to help keep the cemetery afloat. By December of that year, they were looking to sell. West View Cemetery was purchased by its former board president, Asa Candler Jr. Candler’s purchase of West View provides yet another example of the cemetery’s close connection to the history of Atlanta. As heir to the Coca-Cola Company, an already nationally popular enterprise, Candler’s fortunes were closely tied to those of the city.

Although his wife, Florence Stephenson Candler, did much of the day-to-day work associated with actually running West View, Candler’s influence proved to be a turning point for the cemetery. He made several significant changes to West View and its character during his tenure, perhaps the most whimsical of which was a trophy room for his big game hunts installed at the base of West View’s water tower. More impactful though, were Candler’s changes to West View’s design as a cemetery.

Changing West View for Changing Times

Asa Candler, Jr., was not a fan of West View’s lawn-park cemetery style. His tastes had evolved with others’ of his generation, and he had come to prefer a style known as the “memorial park.” Memorial park cemeteries were intended to resemble exactly what their name described: parks, more than graveyards. Rather than being organized around large family monuments surrounded by smaller individual markers, memorial park designs called for large, often plantless, lawns, designated by one sculpture in their center (typically biblical in theme), which would be surrounded by flat, bronze markers. As they aged, these markers would develop a green patina that allowed them to blend in with the grass around them. The fact that they were flush with the ground also made them significantly easier to maintain – a lawn mower could be driven directly over them.

Candler’s enthusiasm for the memorial park was not shared by all of the families who owned plots in West View. Though Candler designated only a part of West View to follow the new design style (a segment called the Garden of Memories), graves that had been purchased before the Garden was established, and a handful of other, older lawn-park graves, were caught up in West View’s remodeling effort. Candler was sued several times by families horrified that the graves of their loved ones had plants removed and markers lowered or flattened privileging, as they saw it, the aesthetic tastes of West View’s wealthy owner over the decisions of paying lot-holders.16 Candler would later cite these suits as a motivating factor in his decision to sell West View in 1951.

West View Abbey

Perhaps even more impactful on West View’s future as a cemetery was the other major design change Candler made, the construction of West View Abbey. Begun in 1943, West View Abbey, which is the largest enclosed mausoleum in the world created from a single set of plans, was an enormous undertaking.17

West View Abbey was constructed from thirty-five different types of marble, imported from across the United States (Tennessee, Vermont, Colorado) and from around the world (Italy, Belgium, Spain).18 The abbey was also constructed in an architectural style rare in the United States: Renaissance Plateresque, a Spanish style chosen by the cemetery to honor Hernando De Soto, one of the first Europeans to travel through Georgia.19 The Abbey, which had the space for over 11,000 burials, was somewhat completed (three quarters of the top floor and the back of the chapel remain incomplete today) to great fanfare in 1949. Advertising, however, began in 1946 at which point the West View Cemetery Association declared it to be a “community mausoleum, challenging the finest the masters of the past ever built” and evoking, or perhaps even eclipsing, “Napoleon’s memorial in Paris, the Taj Mahal in India, and Westminster Abbey in London.”20 It received its first burial, Elizabeth Allan, that same year.

Becoming Today’s Westview

Candler departed from West View just two years later, when he sold the cemetery to a management company based in Washington, D.C. and headed by L.O. Minear, Chester J. Sparks and Grover Godfrey Jr. Minear and Candler’s transaction wasn’t made public but was known to be “the biggest cemetery transaction on record” in the United States.21 Despite Minear’s significant investment in Westview (the spelling changed when he purchased the cemetery from Candler), he only managed the cemetery for a year before selling it to Frank C. Bowen and other investors in 1952. The Bowen family continues to manage Westview today and have been in charge of the cemetery for more than half of its existence.

Throughout the mid-to-late twentieth century, Westview was again impacted by the same historical moments and challenges as Atlanta. It struggled to sell plots at the same rate as Atlanta’s white residents moved to the suburbs and invested in burial plots closer to their new homes, and was was officially integrated in 1970.22 From the 1980s to the early 2000s, Westview yet again changed its style as a cemetery to accommodate Atlantans’ changing funerary tastes, erecting several columbaria, or niches to hold cremated remains. Efforts were first begun to add Westview Cemetery to the National Register of Historic places in 2001, and it was finally successful in its application in June of 2020.23

As it has reflected changes in Atlanta over time, Westview has also reflected the impact of the city’s people and their influence on Atlanta’s trajectory as a city. Though cemeteries are windows into the history and culture of the places they’re associated with, they are also burial places that often include details and tributes to the lives of the countless individuals who choose them as a final resting place. In the case of many of the individuals buried at Westview, Atlanta History Center houses pieces of their lives in our archives. Check out the list below to learn more!

Notable Residents

-

Proprietor of Whitehall Tavern, one of the first businesses in the city, died in 1855 and was reburied in Westview in 1890. Whitehall Street, now known as Peachtree Street, was originally named for Humphries’ tavern.

-

Atlanta real estate investor for whom Grant Park is named. Grant was also an engineer and helped design Atlanta’s defenses against Union General W.T. Sherman during the Civil War.

-

Atlanta real estate investor who helped establish the iconic neighborhoods of Druid Hills and Adair Park.

-

The man who raised the U.S. flag over Manila during the Spanish-American war. Brumby didn’t get to enjoy his military glory for long. He died of typhoid shortly after returning home to Atlanta.

-

One of the first surgeons to work at Grady hospital.

-

The architect who designed Rhodes Hall and the private home now known as Wrecking Bar in Inman Park.

-

Author of the Uncle Remus stories and Atlanta Constitution journalist.

-

President of Rich’s department store

-

-

Mayor of Atlanta for decades, Hartsfield oversaw many of the developments that made Atlanta what it is today, in particular the airport which now bears his name.

-

Atlanta historian and artist, known for his work on the Civil War, in particular his restoration of the Battle of Atlanta cyclorama and serving as an historical advisor on the set of Gone With the Wind.

-

One of the first African Americans to hold an executive position on a major league baseball team (the Braves).

-

Founder of the Varsity

-

President and CEO of the Coca-Cola Company for much of the late twentieth century, Woodruff is perhaps best known for his enormously generous (and frequently anonymous) philanthropic investment in Atlanta.

-

Founder of the Cherokee Garden Library, which is located at Atlanta History Center

-

A prominent collector of Civil War artifacts whose collection forms the base of Atlanta History Center’s.

-

Whose house, Smith Farm, is now a part of Atlanta History Center’s exhibits

-

A famous cookbook and cooking column author, beloved for her adaptation of traditional Georgia recipes.

-

The man who donated the Cyclorama to the City of Atlanta

-

First lady of Atlanta from 1901-1903.

-

Engineer of one of the locomotives (the William B. Smith) involved in what is now known as the Great Locomotive Chase.

-

A prominent porcelain artist.

-

Editor of the Atlanta Constitution and one of the first public articulators of the New South ideology across the United States.

-

Heir to Coca-Cola and owner of West View Cemetery from 1933-1951.

Footnotes

1 Eve Phelps, “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Westview Cemetery,” 2001, 3, Cothran-Danylchak Papers, Series I, Box 8, Folder 17, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

2 Franklin M. Garrett, “West View Cemetery: A Short Account of Its History,” 1987, 2, Subject File, Cemeteries – Westview Cemetery and Abbey, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center; Jeff Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery (The History Press, 2018), 32, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center; Phelps, “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Westview Cemetery,” 3; John Soward Bayne, Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery (Vanity Press, 2014), 10, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

3 Garrett, “West View Cemetery: A Short Account of Its History,” 1.

4 Garrett, “West View Cemetery: A Short Account of Its History,” 1.

5 Andy Ambrose, Atlanta: An Illustrated History (Hill Street Press, 2003), 93; Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 27.

6 “Mrs. Haskins Buried,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), October 9, 1884.

7 Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 16–17.

8 “Development of West View Cemetery August 6,1884 AJC,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), August 6, 1884.

9 Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 53.

10 Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 35.

11 Garrett, “West View Cemetery: A Short Account of Its History,” 2.

12 The Atlanta Constitution, “Development of West View Cemetery August 6,1884 AJC.”

fn_113 “Battle Monument Association,” The Atlanta Journal (Atlanta, Georgia), March 9, 1885, https://www.newspapers.com/image/968888156/?match=1&terms=%22The%20Blue%20and%20Gray%22%20AND%20%22West%20View%20Cemetery%20Association%22.

14 Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 46–47.

15 Clemmons, Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery, 55.

16 Bayne, Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery, 10.

17 Phelps, “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Westview Cemetery,” 1.

18 Phelps, “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Westview Cemetery,” 1.

19 West View Cemetery Management, “An Introduction to Westview Abbey,” ca 1945, Subject File, Cemeteries – Westview Cemetery and Abbey.

20 West View Cemetery Management, “Shadows of Paradise,” ca 1940, Subject File, Cemeteries – Westview Cemetery and Abbey, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

21 Margaret Shannon, Candler Sells Cemetery Here: Three Experts Buy West View in Record Transaction of Type, ca 1951, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center (Subject File, Cemeteries – Westview Cemetery and Abbey).

22 Bayne, Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery, 112.

23 “National Register Database and Research – National Register of Historic Places (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed September 10, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/database-research.htm.