Europeans dreamed of growing grapes and producing wine in colonial Georgia. Consulting early 18th-century maps, they concluded that colonial Georgia was located at the same latitude as Madeira, a warm subtropical island off the coast of North Africa, famous for wine production.

In October 1732, the Georgia Trustees paid William Huston 75 British pounds to visit Madeira, learn the art of winemaking, and then take cuttings to South Carolina and Georgia. For the next several years, ships bearing “mulberry plants,” “burgundy vines,” and “vine cuttings from France” arrived in colonial Georgia.

Yet the North American weather proved fickle, and a frost in March 1739 damaged the vines and citrus plants that had been planted along the Georgia coastline. By the time the charter expired in 1752, most Georgians realized that large-scale wine production was an unattainable pipe dream.

Instead, British colonists imported wine and distilled spirits from Europe and the Caribbean. In Georgia, the Savannah Custom House estimated that 42,226 gallons of West India Rum, 31,715 of North American rum, and approximately 7,056 gallons of wine entered the port of Savannah and Sunbury during a three-year period commencing in January 1769.

Accounting “half a pint per day [of rum] for each white person upon average” and “one pint per day [of wine] for 160 people upon an average; for as yet the inhabitants are not in affluence enough to use it generally,” colonial Georgians consumed approximately 159,687 gallons of rum and 7,308 gallons of wine.

Since the 1600s, colonial women in British North had been producing “small beer,” a low-alcohol beverage often made with molasses, for their individual households. The process was not easy, and makers relied upon taste, smell, and texture to ensure a safe and consumable product. Claude Durand, a French Huguenot traveling in Virginia during the 1680s, was amazed at the quantities of cider being pressed and consumed.

They, he recalled, “requested to drink so freely ‘that even if there were twenty, all would drink to a stranger and he must pledge them all.” During the second half of the 18th century, an increasing number of Georgians began distilling spirits, or brandy, for home consumption and commercial sale. In the 1760s, Georgia appears to have opened its first larger distillery near Savannah, producing either molasses rum or fruit brandy. Between 1769 and 1772, the Savannah Custom House estimated that 5,000 gallons of rum were produced domestically in the colony.

Before the American Revolution, rum and molasses accounted for one-fifth of all goods imported from British territories. That trend continued into the 1790s when rum and molasses still accounted for approximately one-fifth of the value of all American imports. By 1810, however, whiskey, rum, and distilled spirits were the third most important industrial products (behind cloth and tanned leather) and accounted for 10 percent of the United States’ manufactured output. While import taxes on rum and rum distilling remained in place, the whiskey tax was repealed in 1802, which made domestically produced whiskey far cheaper than imported rum. As prices dropped, the United States became a nation of whiskey distillers and drinkers.

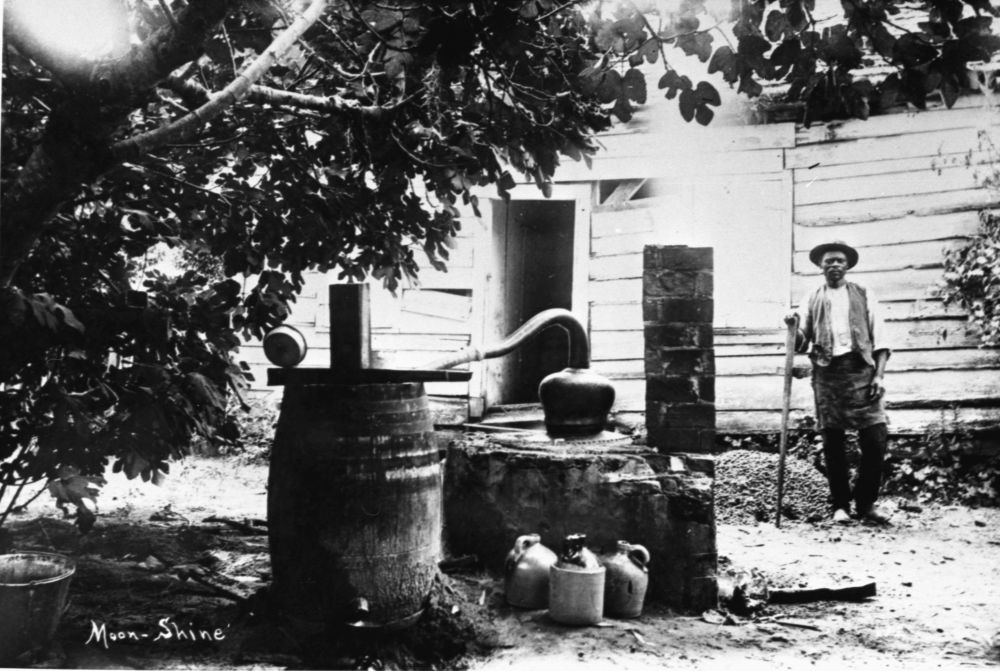

In the nation’s early years, distilling functioned as a means of using excess grain. According to historian W. J. Rorabaugh, “the process of distillation interested Americans because it performed a vital economic function by transforming fragile, perishable, bulky, surplus fruit and grain into non-perishable spirits that could be easily stored, shipped, or sold.”

A bushel of corn worth .25 cents could be distilled into 2.5 gallons of spirits worth at least $1.25 — a handsome and welcome profit for most 19th-century farmers, including those who paid a commercial distiller. Copper stills, boilers, and bowls were expensive, and only wealthy farmers and planters could afford to purchase distilling equipment.

According to Harrison Hall’s 1818 distilling manual, equipment alone cost $1,124, but within three months could yield a $676 profit. Smaller farmers, who lacked the necessary investment capital, often paid wealthier neighbors to distill excess crops. Yet whiskey was a fickle business rife with price fluctuations, and not all farmers profited.

For many 19th-century farmers, distilling provided a means to increase profits and to use excess grain and fruit. According to an 1855 agricultural journal, the ideal agricultural institute consisted of 640 acres of land for cultivation, 100 acres of meadows, and 200 acres of pasture land in addition to a 10-acre vineyard, 4-acre hop garden, and a 20-acre orchard to “show the process of making cider.” Average southern farmers, of course, were not developing full-scale agricultural institutes. Still, the article would have represented the ideal 19th-century farm and served as an aspiration for farmers cultivating their lands. By the mid-19th century, even lower-class white Georgians produced homemade brandies and ciders on their small farms for personal consumption.

In 1893, Georgia had 91 operating grain distillers, transforming malt, rye, and corn into alcohol. Small-scale fruit distilling also remained popular throughout the state, and that same year, 335 fruit distilleries produced 5,069 gallons of apple brandy and 29,887 gallons of peach brandy. Georgia was a leader in the production of distilled spirits, and only New York, Kentucky, and Virginia had more distilleries.

By the late 19th century, distilling — like many other businesses — had transformed from a rural, localized industry into a modernized national economy, and Georgia was home to several large-scale distilleries.

In 1867, Rufus M. Rose moved to Atlanta and began selling wholesale wine, liquor, and cigars. By the 1870s, he operated a retail store in downtown Atlanta and ran distilleries in Vinings, Georgia and Chattanooga, Tennessee. In 1894, he incorporated the business under the name R. M. Rose Company and, alongside his son Randolph Rose, ran the company while also serving as the secretary and treasurer of Mountain Spring Distillery, which produced “pure hand-made Georgia corn whiskey.”

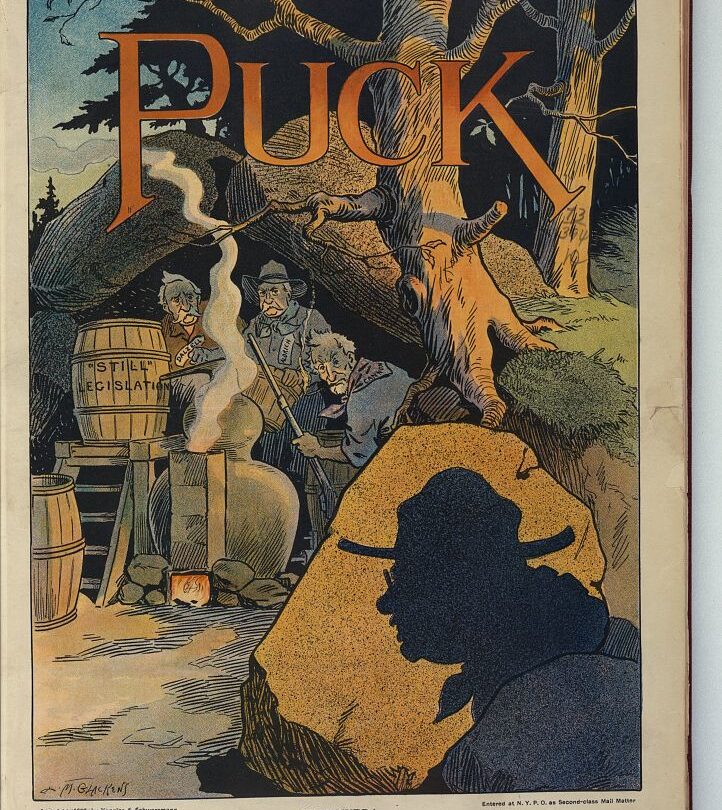

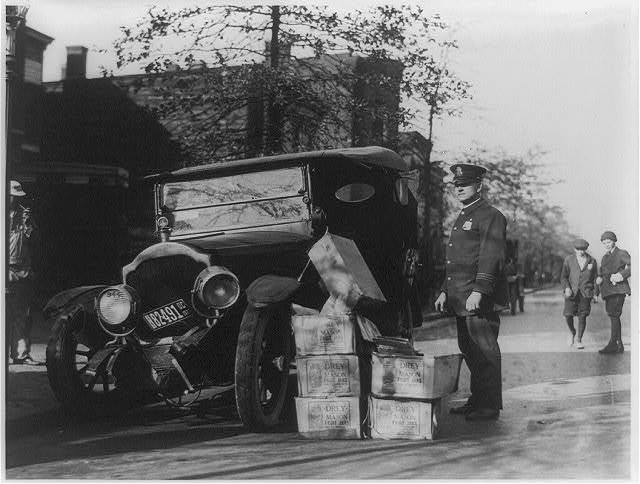

In 1907, Georgia passed the State Prohibition Act, which prohibited “the manufacture, sale, barter, giving away to induce trade, or keeping or furnishing at public places, or keeping on hand at places of business of any alcoholic, spirituous, malt or intoxicating bitters, or other drinks, which if drunk to excess will produce intoxication.” While underground operations continued, legal whiskey distilling stopped in Georgia and resumed only in 1935, after the repeal of statewide prohibition.