The hamlet of Dahn, Germany as seen from the “Wachtfelsen” rock formation. Nemracc, Wikimedia Commons

Dahn is a tiny hamlet in a picturesque area of Germany, located just a few miles from the French border. It lacks notable figures, significant architecture or monuments, cultural events, and tourist attractions. However, for soldiers serving in the U.S. Army’s 42nd Infantry Division, known as the “Rainbow Division,” Dahn is the site of a memorable celebration of freedom during World War II. This celebration marked the end of Hitler’s Nazi regime, more than a month before the end of the war in Europe.

Howard Margol describes his experience celebrating Passover in a combat zone as part of the U.S. Army’s 42nd Infantry Division in 1945 during World War II.

Jewish twin brothers Hilbert and Howard Margol were with the Rainbow Division when it crossed the Rhine River into Germany in March 1945.

“When we crossed over into Germany, one of our division chaplains, Rabbi Eli Bohnen, noticed that Passover was early that year. So, he contacted [Rainbow Division Commanding Officer Major] General Collins and told him that it would be great if they could arrange for a Seder,” said Hilbert.

General Collins understood the significance of holding Passover in a newly captured German town and quickly agreed.

“With General Collins’ help, Rabbi Bohnen and his jeep driver went back to France,” said Howard. “They rounded up French wine, fresh chickens, and a lot of fresh food that we were not able to have, and we had a regular Passover Seder in Dahn, Germany.”

Hilbert Margol describes his experience celebrating Passover in a combat zone as part of the U.S. Army’s 42nd Infantry Division in 1945 during World War II.

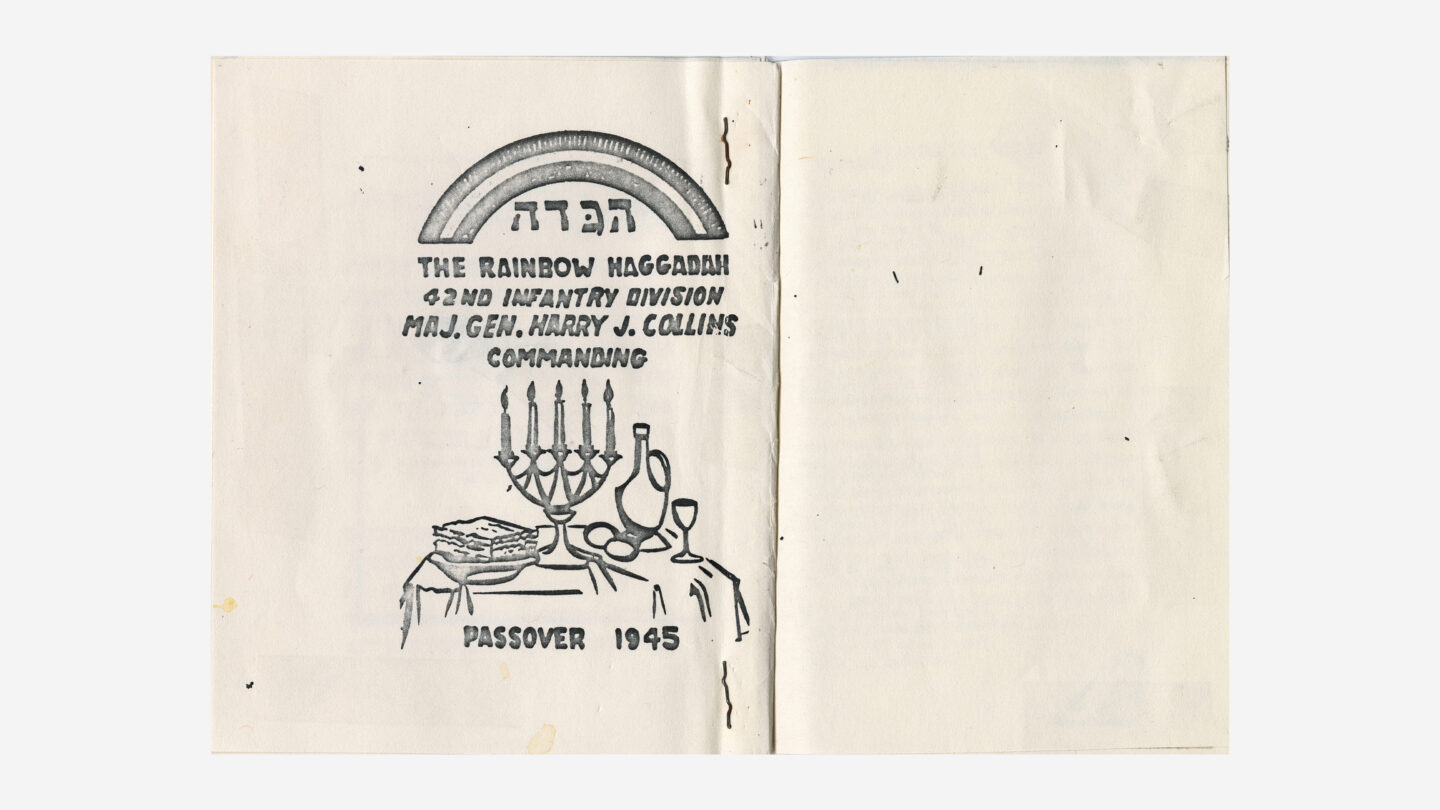

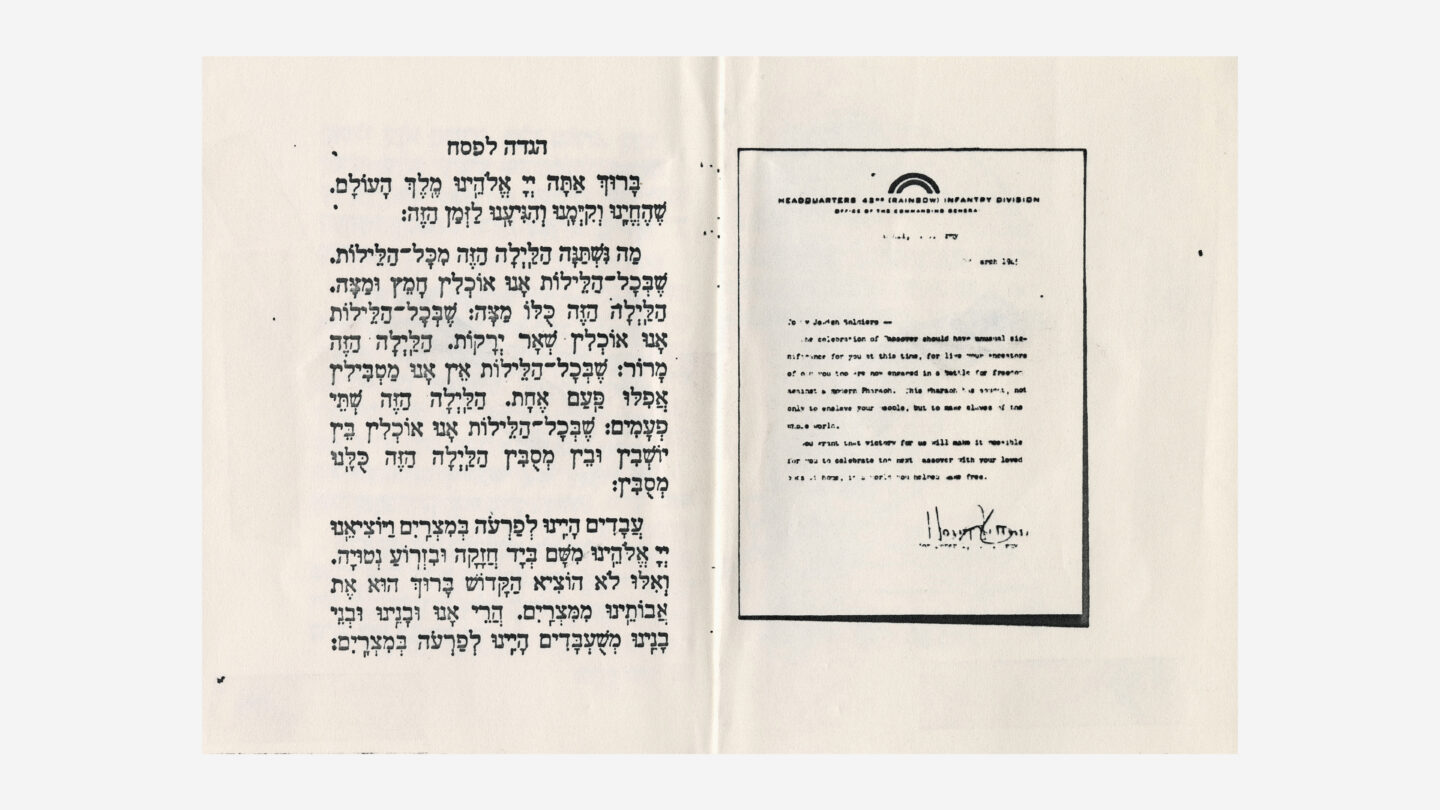

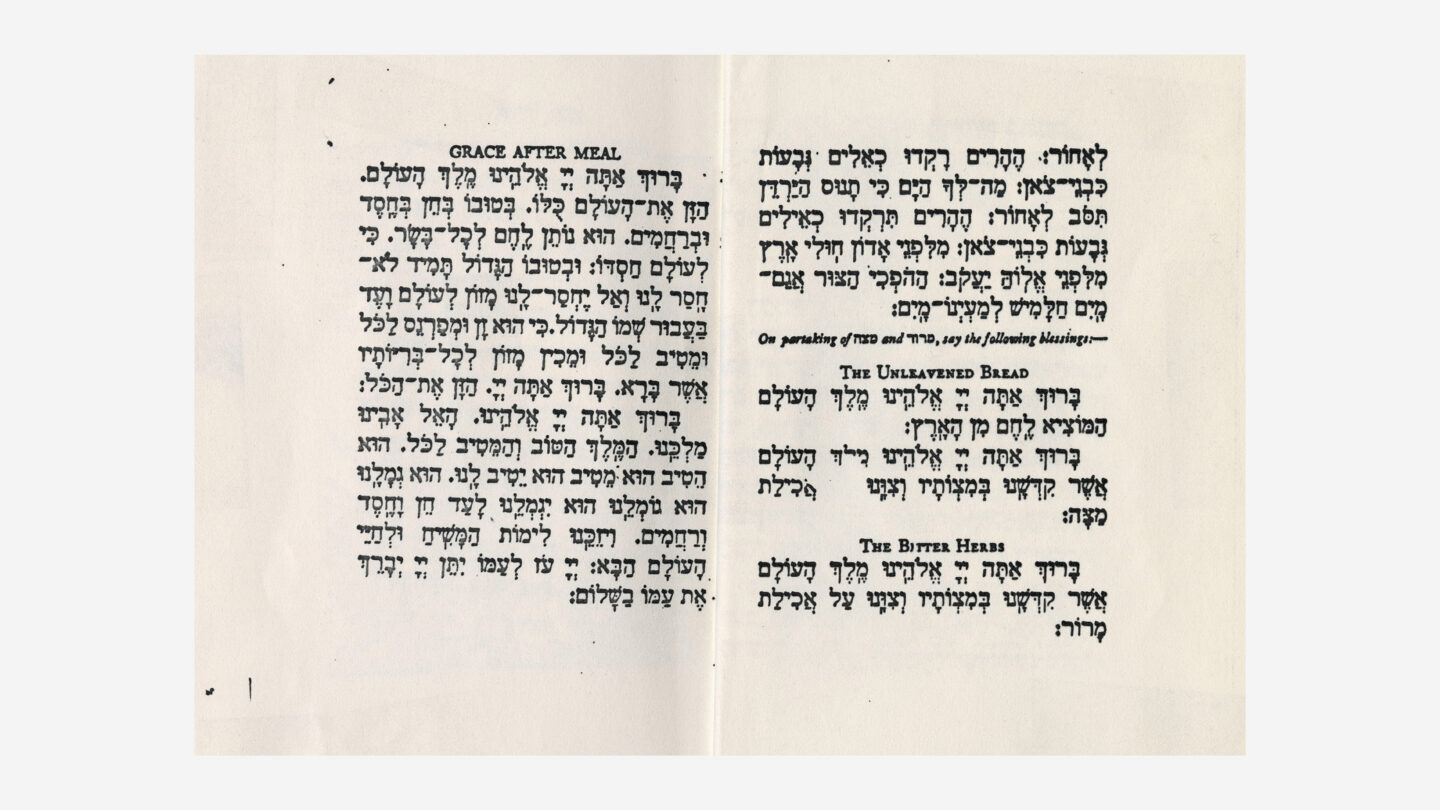

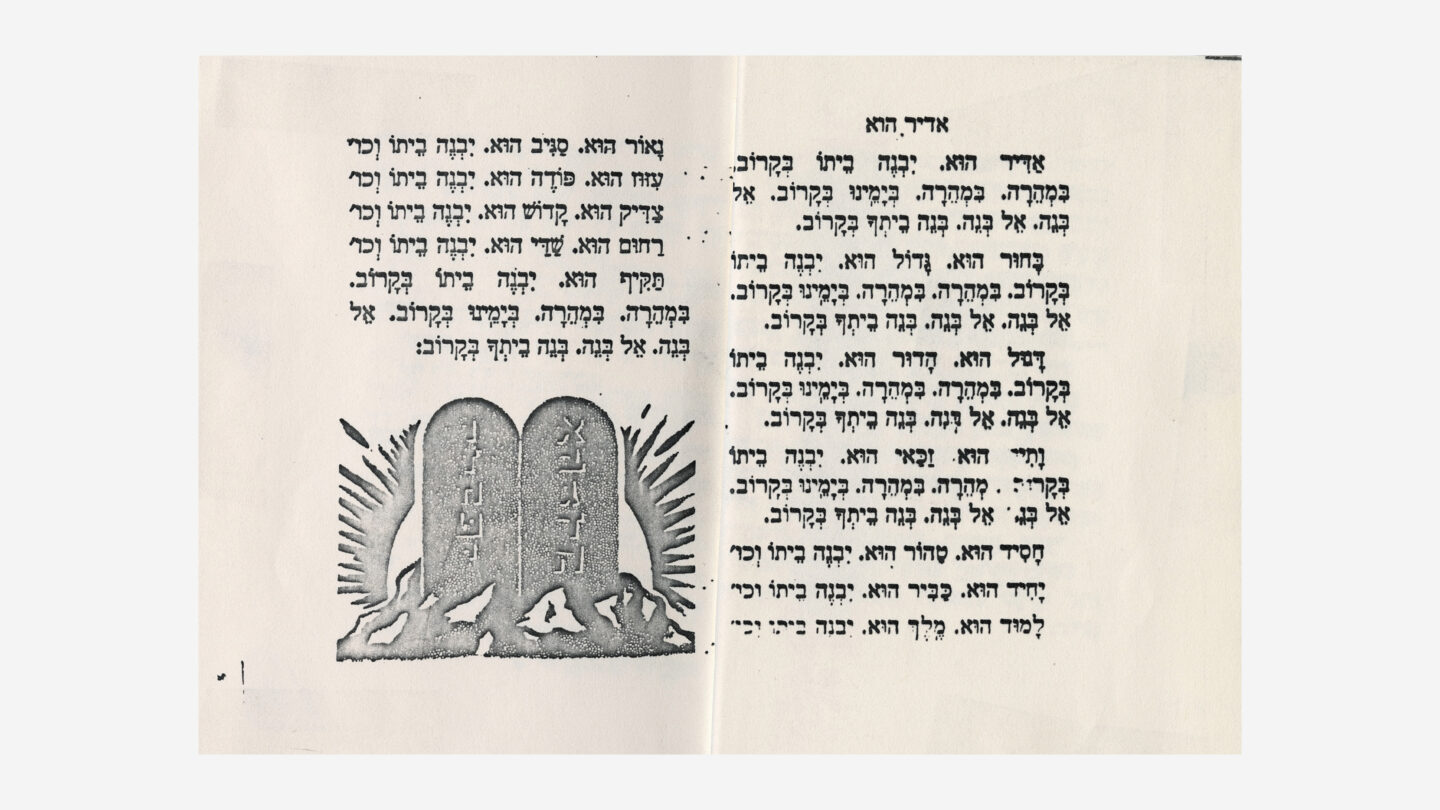

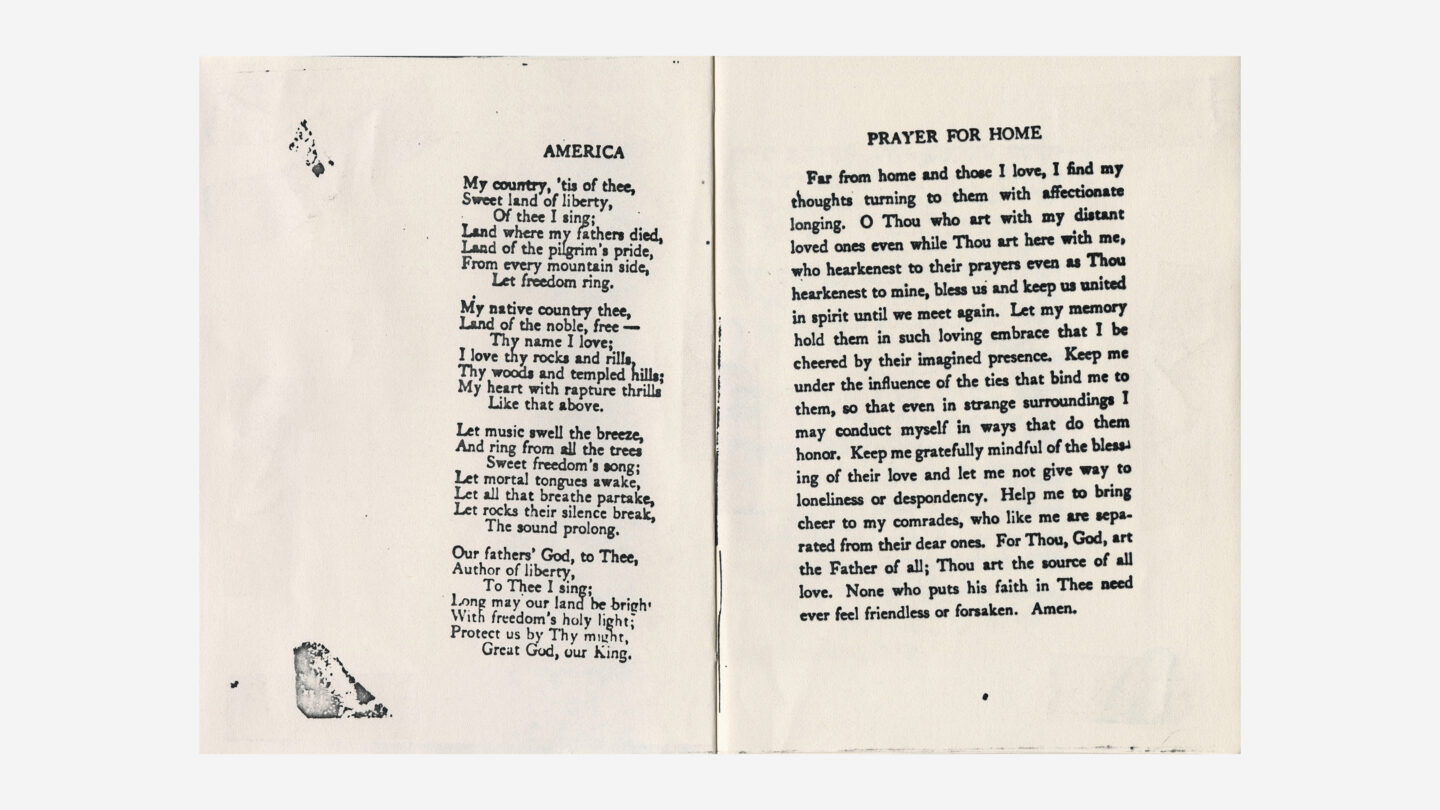

The only thing missing for the service was the Haggadah, the ceremonial text required for the ritual meal. The word Haggadah means “telling,” and its purpose is to tell the story of the Jews’ Exodus from Egypt and guide guests through each ritual, explaining when, how, and why each rite is performed. The Jewish Welfare Board in New York sent Passover Haggadahs for the troops that year, but they didn’t arrive in time because the 7th Army was advancing so rapidly.

Rabbi Bohnen and Chaplain Assistant Corporal Eli Heimberg, improvised. They used the same press in Dahn that printed their division newspaper and crafted a makeshift Haggadah for this special Seder in a combat zone.

Bohnen wrote in an April 1945 letter to his family, “You may also be interested to learn that the soldiers who did the actual printing told us that when they had to clean the press before printing the Haggadah, the only rags available were some Nazi flags, which for once served a useful purpose.”

“They even printed a special Passover Haggadah, a little prayer book, for the occasion, and I still have my copy. It’s one of the few copies probably left in the world,” said Howard.

“Anyway, it was very interesting. Aside from the fact we had fresh food, it was held in a former German school building in the cafeteria. They brought in Jewish soldiers from not only the 42nd Division but other units in the area, and we had about 1,500 soldiers at that Passover Seder. The Army cooks prepared the food, of course.”

Hilbert added, “The best part about it was they had German civilians serve us. They cleaned up everything. So that was a vivid memory.”

U.S Army soldiers guard the gates in front of the main entrance to the Dachau concentration camp, 1945. National Archives

Reflecting on that day, Howard said, “It really struck me emotionally that was in late March and about 28 days or so later, April 29, 1945, we liberated the concentration camp of Dachau. So, I felt that here a few weeks before we were celebrating the liberation of the Jews from Egypt, and here a few weeks later we liberated the Jews that were in the concentration camp of Dachau. So, from that standpoint, it was very meaningful to me.”

The “Rainbow Haggadah,” written almost entirely in Hebrew, ends with an English “Prayer for Home” instead of the traditional Passover prayer, “Next Year in Jerusalem.” The concluding song is “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.”