View of the Prince Hall Masonic Temple on Auburn Avenue in the Sweet Auburn neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia, 1978, Atlanta Urban Design Commission Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center.

As of February 11, 2026, Atlantans once again get to see one of Atlanta’s most significant buildings in its full glory after a comprehensive restoration. Few places in Atlanta—or in the nation—concentrate as much African American history within a single structure as the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge building on Auburn Avenue.

Within this ornate yellow-brick building operated WERD Radio, the first Black-owned and directed radio station in United States; a franchise tied to the legacy of Madame C.J. Walker, who became America’s first self-made, female millionaire; and, most famously, the headquarters of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. From offices here, Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Young, Ella Baker, Ralph David Abernathy, and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement helped organize campaigns that would change the course of American history.

At the center of it all stood the Prince Hall Masonic Grand Lodge. For generations, the Prince Hall Masonic Order has served as a pillar of the Black community in Atlanta and across the country. Especially in the era immediately following the Civil War, Prince Hall Masons emerged as leaders, helping to usher in new eras of prosperity and leading efforts to overcome the strident barriers of Jim Crow Segregation. Now, Atlantans will be able to explore this history in the halls of the very building where it all happened.

Prince Hall Masons History

The tradition of Black involvement in the ritual and traditions of the Freemasons dates to the Revolutionary War. On March 6, 1775, a free Black man named Prince Hall and fourteen other Black men were initiated into Freemasonry by Lodge No. 441 of the Irish Registry, a military lodge attached to the 38th British Foot Infantry stationed at Castle William Island in Boston Harbor. Following the British departure from Boston, Hall and the others no longer had a formal lodge affiliation. Hall attempted to form his own legitimate Lodge to continue their involvement, but the Massachusetts Grand Lodge rebuffed him.

It was another British entity, the Grand Lodge of England, considered the premier Lodge at the time, that eventually granted a charter on September 29, 1784 for African Lodge No. 459, the first Black Masonic lodge in the United States. Under Hall’s leadership, additional Lodges were formed as Black Freemasonry spread across America. In 1808, a year after Hall’s death, a few lodges met and formed as the African Grand Lodge. Later, in 1847, the organization renamed itself the Prince Hall Grand Lodge to honor its founder. For many years, despite its roots from English Masonic authority, white Masonic Lodges within the United States refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Prince Hall Lodges.

Fraternal orders formed important cornerstones of Black cultural life in the South and around the United States. Often serving as sources of aid and support, fraternal organizations also offered points of connection and socialization with community members, forming important bonds that often extended into business and cultural life. In the South prior to the Civil War, such societies were greatly limited by laws and practices banning Black people—even free Black people—from gathering for meetings. In Georgia, the 1848 Slave Codes restricted large gatherings and worship services.

As Reconstruction began and the legal system in the South was radically reshaped following the destruction of slavery, Black people gained access to voting rights and citizenship protections, often for the first time. Nearly 40% of the population of the former Confederate states were enslaved prior to the end of the Civil War—4,000,000 people were suddenly freed and trying to build lives and societies in what was often a difficult and hostile environment.

It did not take long for Black fraternal organizations to take root in helping with this transition. Reverend James M. Simms traveled to his home city of Savannah, Georgia from his residence in Boston to establish Eureka Lodge No. 1 on February 4, 1866, bringing the Prince Hall Masonic order to Georgia within a year of the Civil War’s end. This Lodge combined with two others to become the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Georgia Free and Accepted Masons in 1870, which then relocated to Atlanta just after the turn of the twentieth century. Dr. Henry R. Butler became the Grand Master in 1901, marking the first time that an Atlantan held the position. His professional office was located on Auburn Avenue.

The Building

Reflecting on his early visits to Auburn Avenue, Ambassador Andrew Young reflected that “it was the truest expression of Black culture that I had seen in one place.”

Atlanta Prince Hall Freemasons had been meeting at several different locations in the area throughout the early 1900s until the Great Depression: Hanley’s Funeral Home, Wheat Street Baptist Church, the Old Fellows Lodge Building, and the Herndon Building. As the Masons grew, there became a desire to have a permanent home of their own—a plan that was set in motion prior to the Great Depression, but one that came to fruition under the leadership of John Wesly Dobbs. Upon his election to the position of Grand Master of the Georgia Jurisdiction in 1932, Dobbs immediately was forced to reckon with the severe financial hardship wrought by the Great Depression. By consolidating Lodges and strategically paying off debts, he managed to increase the membership once again and weather the storm. In 1940, the building at 330 Auburn Avenue was finally completed.

From the beginning, the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge building was not just home to the Masons. The women’s auxiliary of the group, the Order of the Eastern Star, also held their meetings in the building. Tenants also leased space in the building, placing those organizations at the heart of bustling Auburn Avenue at the nexus of power in close proximity to the influential members of the Prince Hall Masons.

Perhaps no tenant is more famous than Martin Luther King, Jr. and his deputy Ralph David Abernathy, whose organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had its headquarters in the building from 1957 until 2007. When thinking about the importance of the Masons, Ambassador Young said, “Masons were committed to brotherhood. Masons were committed to serving the community, and Masons were particularly committed in the South to registering voters.” During the time that the SCLC was located in the building, “with all of the Hell we raised and all of the freedom we achieved, we seldom had more than 15 or 20 people [in the offices.]”

Also key to the building’s role in shaping the political and social movements of the Civil Rights era was WERD Radio, the first Black-owned and directed radio station in the entire United States. Founded in 1949, the station broadcast music, including Black jazz and blues performers during the restrictive Jim Crow era, as well as speeches from King and other Civil Rights leaders. Other businesses had their offices in the building as well, including a dentist, barber, and a franchise of Madame C.J. Walker beauty salon.

The Prince Hall Masons Building Today

Consistent with challenges with all aging buildings, the upkeep of the large Prince Hall Masons Building became more difficult as tenants left Auburn Avenue and the footprint of Atlanta changed. In 1992, the National Trust for Historic Preservation included the entire Sweet Auburn Historic District on its annual America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list. In 2012, it included the district once again, recognizing the ongoing challenges associated with deterioration and lack of sustainable development.

View of attendees at the 1989 Sweet Auburn Festival on Auburn Avenue. The Prince Hall Masonic Lodge can be seen to the left. Bud Smith Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center.

In 2021, the lodge received a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation designed to help preserve African American landmarks, funding a preservation plan to guide the building’s restoration. Organizations like Sweet Auburn Works worked alongside the Prince Hall Masons to formulate a plan for restoring the building and its important role in the Auburn Avenue community.

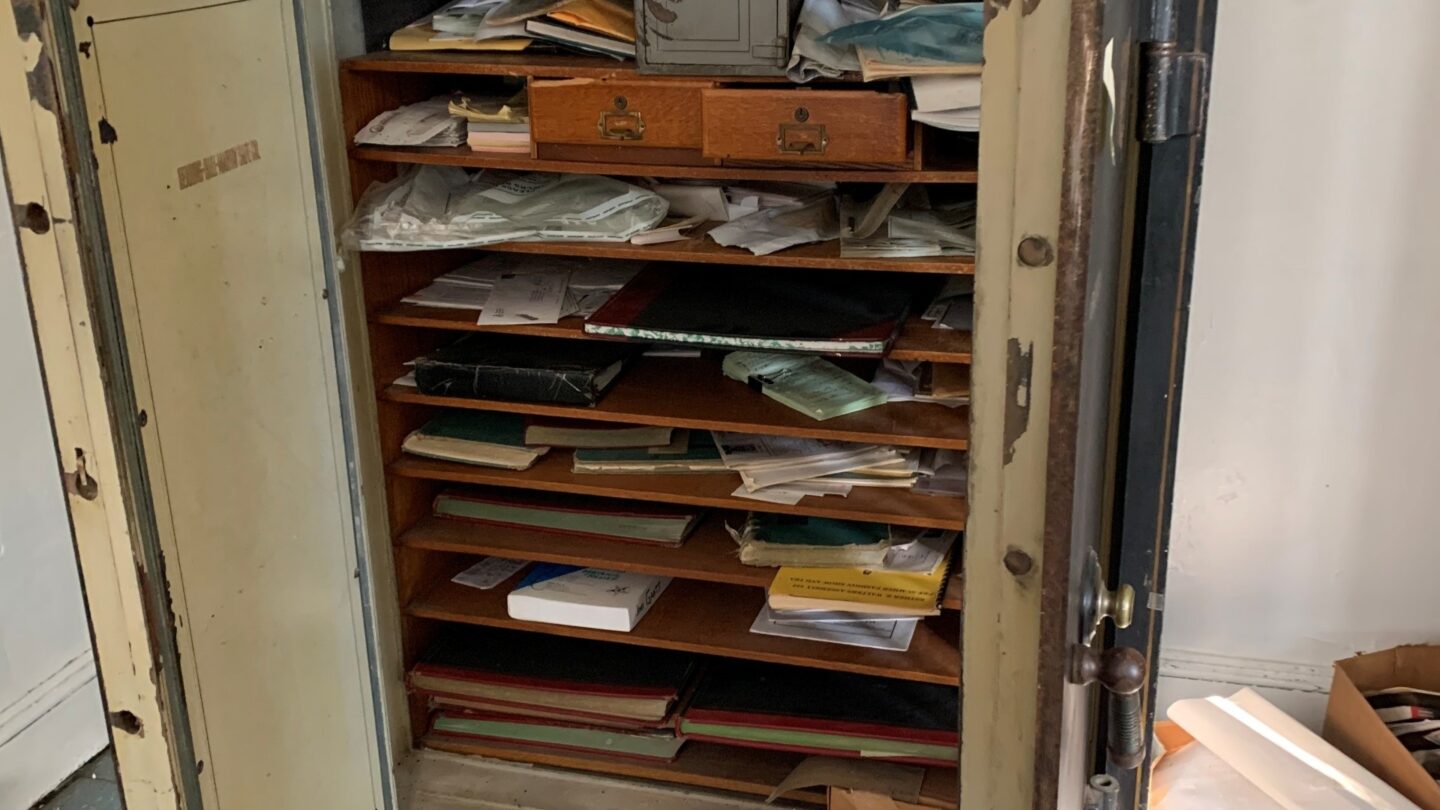

In 2022, building upon 45 years of work with the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historical Park, Trust for Public Land joined forces with the Masons to help raise the necessary funds and manage restoration of the building. Like all historic preservation projects, this one yielded some surprises: Atlanta History Center assisted the Masons in transporting 125 boxes of historical documents, photographs, and other materials out of the building for cataloging and preservation. Former Ambassador and Civil Rights leader Andrew Young also returned to the site of his former office when he worked for SCLC to reflect on his experiences with the Masons and in the Prince Hall Masons building at the height of the Civil Rights movement.

“Historic preservation isn’t just about saving a building. It’s about saving everything that the building represents and preserving that for future generations,” said Sheffield Hale, President & CEO of Atlanta History Center, lifelong Atlantan, and Trustee Emeritus of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.“Kudos to the Masons, the Trust for Public Land, Bank of America, and the Atlanta foundation community for making this complex and ambitious undertaking possible. I look forward to the National Park Service’s plans to recreate King’s SCLC office.”

On February 11, 2026, the fully restored Prince Hall Masons building reopened. As the entire Sweet Auburn District continues to work towards revitalization alongside historic preservation, having such an important building in the community, one that served as a prime center of activity, is important to the overall effort. Preserved as both a site for future Masonic activity as well as a location for historic interpretation and future tenants, it continues to serve as a pillar and lynchpin of one of Atlanta’s most interesting and historic streets.