A Gathering in a Segregated Atlanta

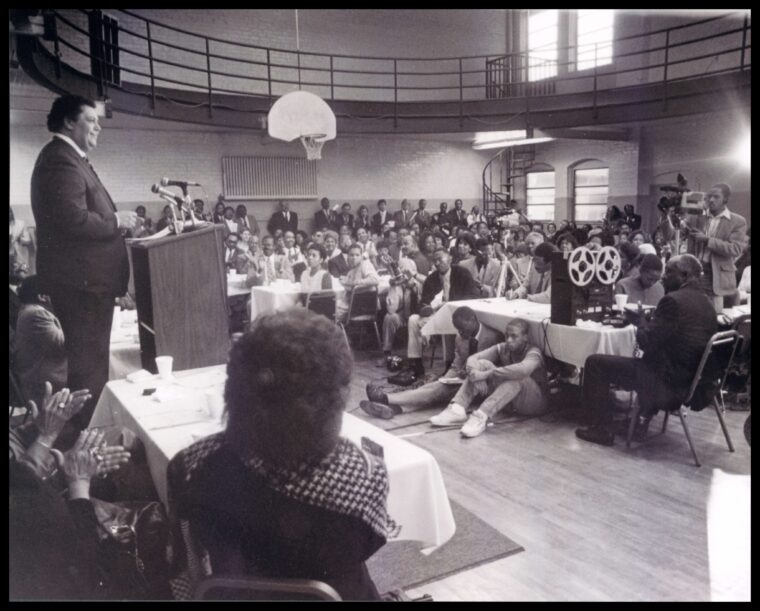

Instead, they sit on folding chairs around tables in the gymnasium of the Butler Street YMCA. A tension fills the air as the interracial group meets because they know that their gathering is illegal. It is 1945, and there are laws against Blacks and whites eating together in public spaces. Despite the danger, the forum will continue to meet regularly over the next 67 years to engage in much-needed interracial discourse.

The group is called the Hungry Club Forum, an interracial speakers’ forum hosted by the Butler Street YMCA, which, in its heyday, was referred to as Atlanta’s “Black City Hall.” Founded in 1894, the Butler Street YMCA became a mainstay of the Sweet Auburn community. During the era of segregation, the Y served as one of the only spaces where Black Atlantans could gather for recreation and community meetings.

From hosting organizations such as the Atlanta Negro Voters League to serving as the first precinct for Atlanta’s first eight Black police officers, the Butler Street Y was a powerhouse for racial progress. Among its most unique and important offerings was the Hungry Club Forum.

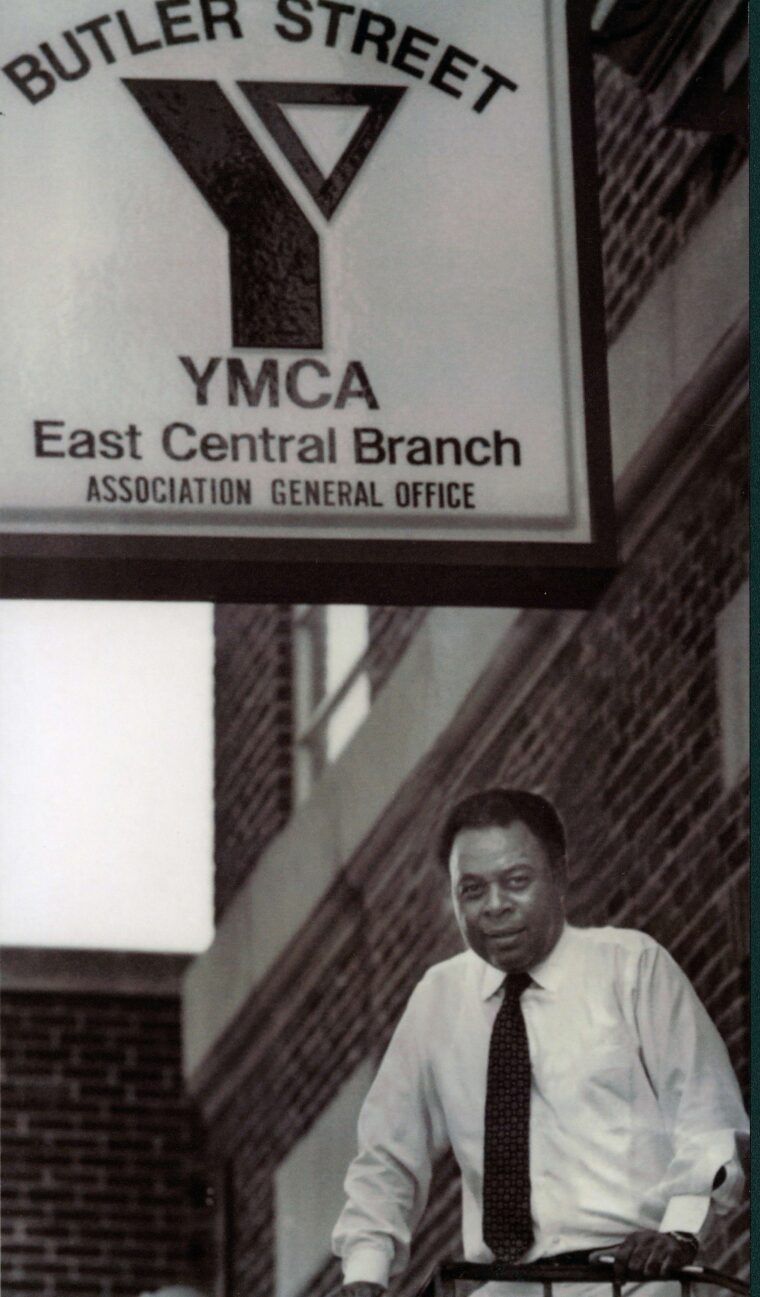

For more than six decades, the forum hosted some of the most notable and influential figures in 20th-century American history. During this time, DeWitt N. Martin Jr. served as president of the Butler Street YMCA. He led the organization from 1975 to 2000, earning the distinction of being the longest-serving president in its history. Martin witnessed some of the Hungry Club’s most significant moments and, even after his retirement, dedicated himself to preserving the story of the forum and the Butler Street YMCA.

DeWitt N. Martin Jr., the president and CEO of the Butler Street YMCA stands near the YMCA sign at the Butler Street YMCA in Atlanta. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Origins of the Hungry Club Forum

From its founding, the Butler Street YMCA stood as a beacon within the Black community, but in the mid-1940s, several Atlantans realized that to further advance African American rights, their efforts could not be limited to within the Black community.

In 1945, during a meeting of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Dr. Ira De Augustine Reid, chair of the Sociology Department at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), expressed the need for a channel of communication between Atlantans of different races. Fraternity members, Atlanta University staff, and Auburn Avenue business leaders developed the idea of creating an interracial lunch-time speakers forum. Dr. Reid dubbed the idea the Hungry Club Forum, stating that it would “provide food for the body and food for the mind.” The concept was presented to Butler Street YMCA Executive Secretary Warren Cochran, who agreed with the idea and allowed the forum to meet in the Y’s gymnasium.

The Hungry Club Forum gathered weekly on Wednesdays at 12:30 p.m. to host a luncheon and a guest speaker who presented on a topic of their expertise.

Many of the Hungry Clubs’ early speakers were educators invited by the forum’s first moderator, Dr. Reid. He drew guest speakers from connections he made while serving at Atlanta University and programs hosted by Atlanta’s historically Black colleges and universities. While topics discussed at the Hungry Club were diverse, issues dealing with race tended to be the most common.

After a few years, the Hungry Club Forum’s weekly meetings developed a typical schedule. The forum met in the Butler Street YMCA every Wednesday around noon, except during the summer months. Those planning to attend called in advance to reserve a seat for the hour-and-a-half meeting that began with a buffet meal served for a small fee. Two menus offered at the forum in 1972 included: roast beef, mashed potatoes, broccoli, and coconut cake; and salmon croquettes, spaghetti, green beans, peaches and pound cake. By providing a meal and conversation, the Hungry Club Forum embraced its motto: “Food for taste and food for thought for those who hunger for information and association.”

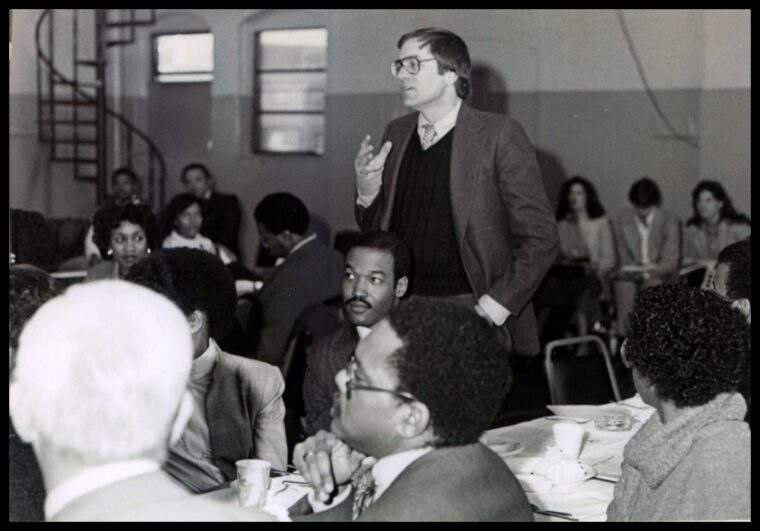

Thirty minutes into the meeting, attendees were introduced to the day’s key speaker, who then delivered their presentation. This was followed by a time for the audience to ask questions and engage in an open conversation with the speaker. The question-and-answer period was intended to facilitate a two-way communication between speakers and the Atlanta community.

A man asks a question during a Hungry Club Forum meeting at the Butler Street YMCA. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Race, Politics, and White Participation

Though the Hungry Club Forum found quick popularity within the Black community, attracting white attendees was initially difficult. Among those most apprehensive about appearing at the Hungry Club Forum were white politicians. Many viewed the idea of eating publicly with African Americans as damaging to their social and political standing. Some long-time attendees of the forum noted that most white politicians only began attending and speaking at the luncheons in the mid-1950s when Black Atlantans became more politically active.

As influential Black organizations such as the Atlanta Urban League and the Atlanta Negro Voters League met at the Butler Street YMCA and collaborated with the Hungry Club Forum, more politicians recognized the significant opportunity afforded to them by speaking at the Hungry Club. Here was a forum for reaching Black voters.

As time passed, apprehensions eased, and both white and Black Atlantans acknowledged the value of the Hungry Club’s interracial platform.

In September 1955, Mayor William B. Hartsfield spoke to the forum and began a tradition of every annual Hungry Club season opening with a speech from the sitting Atlanta mayor.

Mayor Hartsfield established another custom by delivering his State of the City address to the forum. During the era of segregation, Black Atlantans were barred from attending the official mayoral address; however, the Butler Street Y provided a venue for them to hear from and interact with the mayor directly. Subsequent mayors Ivan Allen Jr. and Sam Massell continued this tradition.

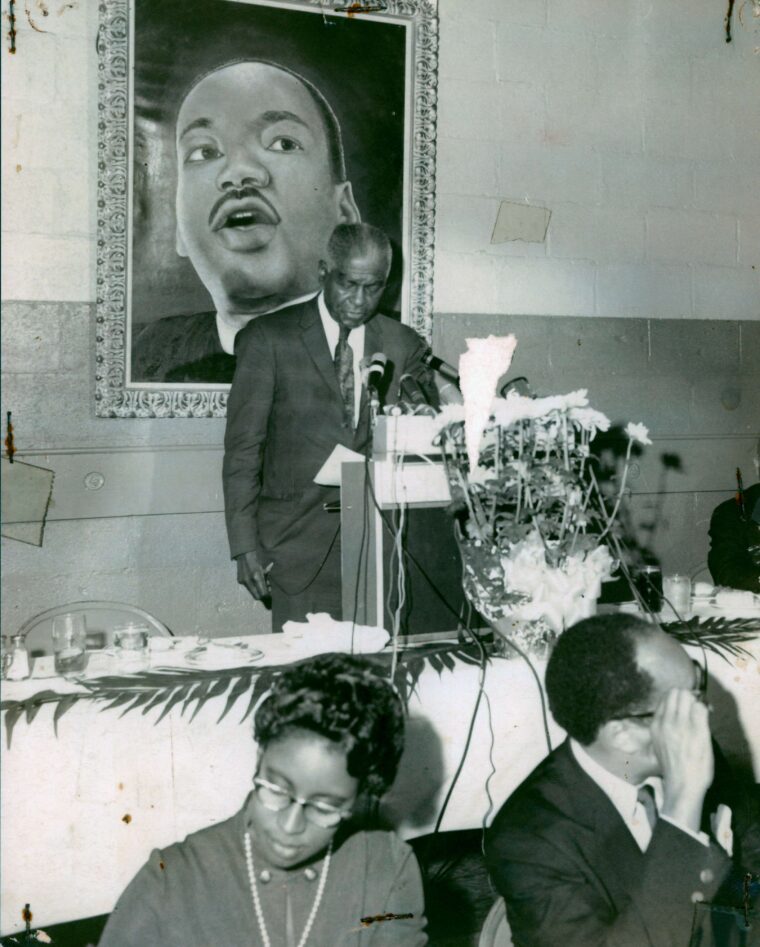

During the Civil Rights Movement, the Hungry Club Forum’s role as a bridge between races proved extremely useful. At the club’s zenith, its effectiveness and prominence in political and social spheres were acknowledged far and wide. By the 1960s, the club’s reputation, not personal connections as in its early days, enabled the Hungry Club Forum Committee to invite and secure speakers of national and international importance who included Atlanta native Martin Luther King Sr., Morehouse College President Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, poet Langston Hughes, and baseball legend Jackie Robinson. Reverend Ralph D. Abernathy used the Hungry Club Forum to announce the famed 1963 March on Washington.

Dr. Benjamin E. Mays addresses an audience at the Hungry Club Forum at the Butler Street YMCA in the 1960s. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who grew up enjoying the Butler Street Y’s recreational activities, returned as an adult to address the Hungry Club Forum on multiple occasions. On May 10, 1967, Dr. King gave a speech addressing what he termed the “Three Evils” — racism, poverty, and war. This appearance marked one of the first times that he openly expressed opposition to the Vietnam War.

Though the forum was a major avenue to advocate for civil rights, the Hungry Club Forum Committee also invited speakers who seemed to oppose the Civil Rights Movement. In 1965, committee members debated the idea of inviting former Georgia Governor Herman Talmadge to address the forum. Talmadge, like his father, former Governor Eugene Talmadge, had a strong reputation as a segregationist. In January of 1966, to the shock of many, Talmadge not only accepted an invitation but also dined with attendees at the forum and stated publicly that he was not opposed to “qualified Negroes” being appointed to federal judgeships or other important federal roles. During the question-and-answer portion of the luncheon, a member of the audience asked him why he hadn’t made such a speech to the forum five or six years earlier. Talmadge responded, “Because you never asked me,” eliciting a burst of laughter from the attendees.

The 1970s saw changes in topics raised by the Hungry Club Forum. As the modern Civil Rights Movement drew to a close, speakers began discussing more intersectional issues related to race, gender, education, and labor. Georgia legislators Betty Clark and Mildred Glover spoke at the Hungry Club. So did civil rights advocate Dorothy Bolden, president of the National Domestic Workers Union of America, who addressed the forum on “the Plight of Black Women.”

The audience at a Hungry Club Forum event listen to a speaker. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The forum’s position as an important political platform expanded beyond city politics. In October 1970, future President Jimmy Carter appeared before the Hungry Club. He faced off against former WSB-TV News Director Harold “Hal” C. Suit as both attempted to garner support for their gubernatorial campaigns (Carter defeated Suit to become Georgia’s 76th governor in 1971).

In 1973, the Hungry Club saw one of its longtime participants, Maynard Jackson, elected as Atlanta’s first Black mayor. His election officially bridged the racial political gap that the Butler Street YMCA had long helped to fill. Rather than needing a “Black City Hall” at the YMCA, Atlanta’s Black community now had its own Black mayor in Atlanta City Hall.

DeWitt N. Martin Jr.’s Leadership and Legacy

Changes in city politics reflected broader trends in the Atlanta community. By 1974, the Butler Street YMCA had begun to encounter financial difficulties. Following the Jim Crow era and desegregation, the Y’s central role in the African American community diminished as a wide variety of alternative recreational, social, and civic gathering places opened to Black Atlantans. The board of directors of the Butler Street Y sought to hire a new “Y Executive” with experience leading YMCA work. They found that leader in DeWitt Nathaniel Martin Jr.

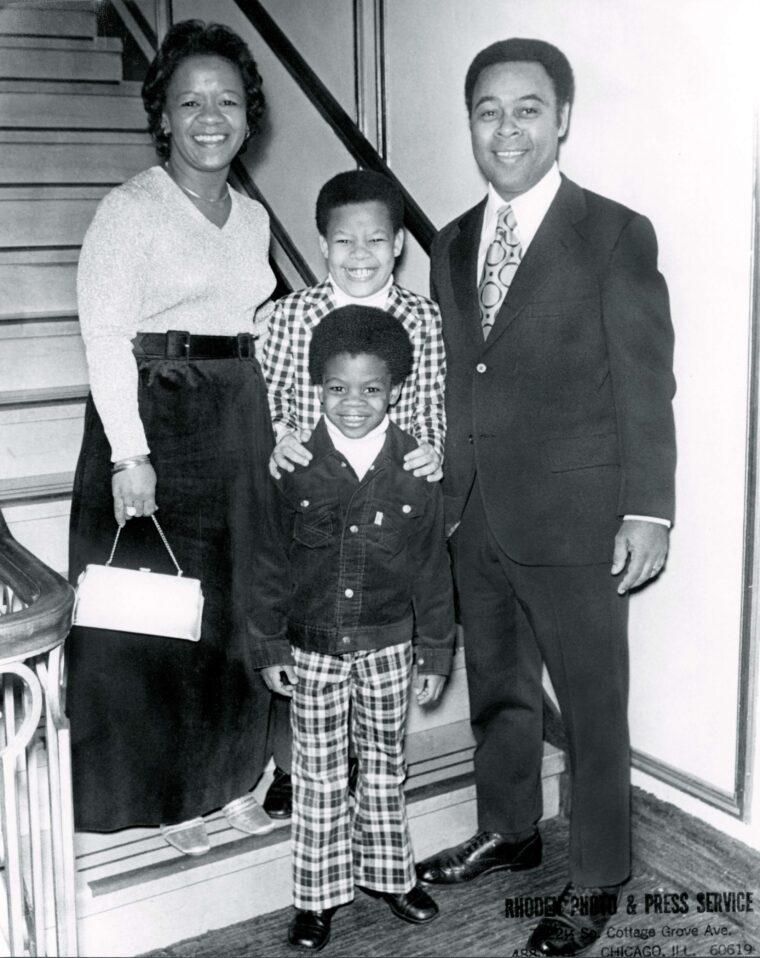

Martin was born in 1933 and grew up in his local YMCA in Chicago. After serving in the U.S. Army as a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division, Martin worked for the city of Chicago. In 1967, he found his way back to the YMCA when he became the first Black director of a Chicago-based YMCA affiliate known as the Off the Street Club. He held the position for two years before being promoted to executive director of the Sears Roebuck YMCA in Chicago. From there, Martin was hired by the Butler Street Y. He moved to Atlanta with his wife, Anne, and sons DeWitt III and DeWayne.

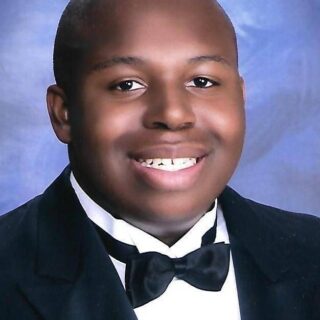

Anne, DeWitt III, DeWayne, and DeWitt Martin Jr., pose for a family photo in 1975. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

On January 2, 1975, Martin began his tenure as president of the Butler Street YMCA. Under his leadership, the Y expanded its programs to fill the changing needs of the community. Between 1979 and 1981, there were roughly 29 youth kidnappings and murders in Atlanta that would become known as the Atlanta Child Murders. Most of the young victims were Black males from economically marginalized communities. As many Black Atlantans feared for their children, the Butler Street YMCA and its six branch locations served as safe spaces for Black youth to gather with adult supervision. Along with providing refuge, the Butler Street Y also partnered with other organizations to conduct weekend search parties to look for missing children. One such search resulted in the discovery of a victim’s body.

Another 1980s crisis that the Butler Street Y addressed was the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The Hungry Club Forum invited Grady Hospital staff and other medical professionals to spread awareness and information about the new disease during a time when it was considered a controversial topic.

While the Hungry Club Forum could no longer claim to be the only venue for interracial discourse, it still played a pivotal role in Atlanta politics. One of the most newsworthy political remarks in Atlanta history was made during a session of the forum in October 1981 during a heated mayoral runoff election. Maynard Jackson, who was barred by law from seeking a third consecutive term as mayor, gave a speech at the forum, endorsing Andrew Young and referring to Black Atlantans who supported opponent Georgia legislator Sydney Marcus as “shuffling, grinning … Negroes.” His words sent ripples through the Atlanta political world and were covered by newspapers across the country. Regardless of the criticism and controversy Jackson’s speech caused, Andrew Young was elected the second Black mayor of Atlanta.

Maynard Jackson speaks to Hungry Club Forum attendees at the Butler Street YMCA in 1981. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Hungry Club Forum continued to be a prominent home for civic discourse on topics ranging from politics and race to city development and industry. The Butler Street YMCA itself also saw a resurgence towards the end of the century under the leadership of DeWitt N Martin Jr. He piloted new recreational and youth leadership programs including the Math Reading & Science Academy, courses in computer literacy, the Black Achievers in Industry (a program that paired young boys and girls with mentors across different professions and industries), and the Youth Aviation Program in partnership with Air Atlanta.

During Martin’s presidency, the YMCA also reached financial stability, paying off all standing property debts and underwriting the construction of two new facilities and an Olympic-sized aquatic center. Along with running the Butler Street Y, Martin also developed national and international programs for the YMCA of the USA, leading Y initiatives such as the Consortium of Black YMCAs and the Caribbean Support Unit for the YMCA of the USA. Martin also became a notable leader in Atlanta, serving on multiple committees to help prepare for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

DeWitt N. Martin greets Andrew Young, and others, while Coretta Scott King speaks with a visitor at the Butler Street YMCA in 1980. DeWitt N. Martin Jr. Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

After 25 years leading the Butler Street YMCA, Martin retired on January 3, 2000. Though he left the organization in better condition than when his tenure began in 1975, the Butler Street Y still struggled to compete with other recreation centers, most notably the YMCA of Metro Atlanta. With continuously rising hurdles to its operation, including a funding cut, the Butler Street YMCA ceased operations in 2012. Along with its closure came the conclusion of the Hungry Club Forum. Among its final speakers was Mayor Kasim Reed, the last mayor to uphold the annual tradition of opening the forum’s new season of noontime meetings.

DeWitt N. Martin Jr, who had continued to serve as president emeritus of the Butler Street Y, was devastated by the Y’s closing. He feared that its rich history and significance would be forgotten. Thus, he dedicated the remainder of his life to organizing personal records from his time at the Butler Street Y. He planned to donate them to archival and educational institutions, including Atlanta History Center, for their preservation.

However, Martin passed away in May 2020, before doing so. Four days before his death, Martin was admitted to Grady Hospital, where he passed away in a room facing Butler Street, only blocks away from the YMCA that first brought him to Atlanta.

In 2024, the Martin family presented archival materials from DeWitt N. Martin Jr.’s papers to AHC, documenting his career at the Butler Street YMCA and fulfilling his hopes that the story of the Butler Street YMCA and the Hungry Club Forum would be preserved for future generations of Atlantans.