Margaret Mitchell and classmates in a class photograph at the Tenth Street School in Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

In the Atlanta where a young Margaret Mitchell spent her tender years, remnants of the past whispered tales of war and survival in the ears of the present. As the sun hung low and painted the summer sky with the hues of twilight, Mitchell, her energy spent on youthful games, would huddle around the stoic figures of her elderly kin. Sitting on the sun-warmed front steps or huddled around the fiery heartbeat of her home on winter nights, she would drink in stories told by those who had lived them.

The tales Mitchell heard from relatives painted the South not as aggressors but as the gallant, wronged party of the Civil War. They spoke of resourceful women and brave men who fought valiantly against insurmountable odds. There was an undeniable undercurrent of romanticism and nostalgia in these stories. The books in her childhood home about the war (all of which she had devoured by age 7) too painted a picture of a South that was not only “gone with the wind” but also sorely missed.

Through this colorful narrative of Mitchell’s childhood, we begin to understand the pervasiveness of Lost Cause mythology, not only in her life — for many likely had similar experiences — but in Southern culture at large.

The Lost Cause

The term, Lost Cause, made its first appearance in print in 1866 in Southern journalist Edward Pollard’s The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates.

The Lost Cause is an interpretation of the Civil War created by Southern whites, many of them former Confederate leaders. The ideology of the Lost Cause converts the harsh truths of slaveholding culture into a pro-Confederate mythology of life in the Old South and the valiant fight to preserve that way of life. The period following the war presented Southerners—both Black and white—with an environment of racial, social, and economic ambiguity. The formerly enslaved were free, and an economy based on forced labor had ended.

Yet, what cultural parameters guided lives in a region conquered and economically destroyed? In the face of this reality, the Lost Cause idealized the South and cast Southern Confederates as courageous, righteous, and, in many ways, triumphant. In doing so, the myth of the Lost Cause distorts history.

The Lost Cause (1869), a painting by Henry Mosler, depicts a weary Confederate soldier standing beside a neglected cabin that represents the destruction of the South in the Civil War and the loss of traditional Southern culture. Morris Museum of Art

Though Lost Cause mythology is centered around actual people, places, and circumstances in a very real conflict, it is not true history. Not because people in the past got their facts wrong — history is more complex than right and wrong — rather Lost Cause mythology is incorrect because it is based more on nostalgic memory than history. The difference between history and memory is that memory is socially constructed rather than objective.

Lost Cause ideology or myth was never codified in a single book or narrative. It was a series of beliefs that have shifted and evolved over time. Core tenants included:

- Secession was not about slavery; it was instead about states’ rights and limited government.

- Slavery was a superior and noble system because those who had been enslaved benefited under bondage and were not ready for freedom.

- The North defeated the South in the Civil War only because the North had more men and resources.

- Confederate soldiers were honorable and gallant. By accepting military defeat gracefully, they won a moral victory over tyranny.

- Robert E. Lee embodied traditional American values and is worthy of national veneration.

- White women aligned with the Confederacy were pure, loyal, and saintly.

Promoting a Memory

Despite the inaccuracy of Lost Cause mythology, the core tenets have become a part of the larger narrative surrounding the South and Southern culture. Undoubtedly, some of this false history was passed on from parents to children, but it was also propagated to future generations through efforts of groups sympathetic to the ideas embodied in the Lost Cause.

Former Confederate soldiers formed one of these groups. Local veterans’ organizations (formed into the United Confederate Veterans in 1889) provided mutual aid, cared for disabled veterans, and carried on the memory of the fallen. They also circulated publications, such as Confederate Veteran magazine, which promoted Lost Cause mythology.

Confederate Veteran, Volume 20, 1912. University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries.

Also, at the forefront of spreading Lost Cause ideology were white Southern women. Groups of these women formed across the South in remembrance of fallen Confederate soldiers. Organized as the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1895, these groups dedicated cemeteries, lobbied for public holidays and shrines honoring Confederate soldiers, and ensured future generations would revere Confederates through educational outreach efforts, including school textbooks in the South.

To guarantee textbooks in the South contained an “accurate” history, the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) created a committee that “resolved to inaugurate a movement to disseminate the truths of Confederate history” at a reunion in Atlanta in October 1919. After the gathering, Mildred Lewis Rutherford, the general historian for the UDC, was tasked with putting together a pamphlet outlining the information an acceptable Southern history textbook should contain. The document, A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books, and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries, delineated 11 essential components of textbooks along with “proof” that backed up her assertions. According to Rutherford, unacceptable textbooks were those that:

- Omitted “the principles for which the South fought in 1861 and does not clearly outline the interferences with the rights guaranteed to the South by the Constitution, and which caused secession.”

- Called “the Confederate soldier a traitor or rebel, and the war a rebellion.”

- Said “the South fought to hold her slaves.”

- Spoke “of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust to his slaves.”

- Glorified Abraham Lincoln and vilified Jefferson Davis “unless a truthful cause can be found for such glorification and vilification before 1865.”

- Neglected “to tell of the South ‘s heroes and their deeds when the North’s heroes and their deeds are made prominent.”

Cornelius Irvine Walker, a former Confederate general who led the UDC-UCV textbook committee, said that the purpose of Rutherford’s pamphlet was to assist those “charged with the selection of text-books for colleges, schools and all scholastic institutions to measure all books offered for adoption … and adopt none which do not accord full justice to the South.”

Georgia History

After the Civil War, under the leadership of John Randolph Lewis and Gustavus Orr, Georgia established public schools to educate the state’s Black and white youth. Georgia history has been taught widely in Georgia schools since 1923, when a law went into effect that mandated instruction in the U.S. Constitution, Georgia’s constitution, and American institutions and ideals. It was not mandatory until 1985 when the Quality Basic Education Act of 1986 stipulated that all Georgians had to learn about the state’s economy, geography, government, and history in the 8th grade.

In 2022, Georgia legislators passed HB 1084, a “divisive concepts” law. It prohibits the teaching of certain concepts, such as the idea that an individual should feel psychological distress based on their race, that individuals are inherently racist or oppressive because of their race, and that anyone is responsible for the actions of people in their race. The law is currently facing legal scrutiny, with critics of the law arguing that it is vague and causes fear among educators regarding discussing race and racism in classrooms.

Currently, Georgia history textbooks have two learning standards for the Civil War that Georgia history educators are compelled to impart to students. These standards cover the causes of the conflict and how Georgia participated in the war.

The standards are as follows:

Analyze the impact of the Civil War on Georgia.

1. a. Explain the importance of key issues and events that led to the Civil War; include slavery, states’ rights, nullification, the Compromise of 1850 and the Georgia Platform, the Dred Scott case, Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, and the debate over secession in Georgia.

2. b. Explain Georgia’s role in the Civil War; include the Union blockade of Georgia’s coast, the Emancipation Proclamation, Chickamauga, Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, Sherman’s March to the Sea, and Andersonville.

A collage of Georgia history textbooks from various decades.

Georgia History Textbooks and the Lost Cause

The role of history textbooks in teaching Lost Cause mythology is key to understanding the disconnect between older and younger Georgians regarding venerating the state’s Confederate past.

To determine whether an understanding gap exists, AHC staff reviewed the chapters devoted to the Civil War in nine Georgia history textbooks available at Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center. These textbooks span a 100-year period. The review compared the Civil War content in the textbooks to the current Georgia educational standards on the subject and noted whether the content addressed the standards.

List of Textbooks Reviewed

- Charles Smith, A School History of Georgia: Georgia as a Colony and a State, 1733-1893. New York: Ginn & Company, 1896.

- Lawton B Evans, First Lessons in Georgia History. New York: American Book Company, 1913.

- James C. Bonner, The Georgia Story. Oklahoma City: Harlow Publishing Corporation, 1958.

- E. Merton Coulter, Georgia: A Short History, Revised and enlarged edition, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960.

- Ruth Elgin Suddeth, Empire Builders of Georgia, 4th edition. Austin, Texas: Steck Company, 1966.

- Albert Berry Saye, Georgia History and Government. Austin, Texas: Steck-Vaughn Company, 1973.

- Lawrence R. Hepburn, The Georgia History Book. Athens: Institute of Government, University of Georgia, 1982.

- W. Bruce Wingo, et al., Georgia in American Society. Stone Mountain, Georgia: Linton Day Publishing Company, 1987.

- Edwin L. Jackson, et al., The Georgia Studies Book: Our State and the Nation. Athens: Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia, 1998.

- Gibbs Smith Publisher. The Georgia Journey. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith Education, 2018.

| Textbook Matrix | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia History Standard | A School History of Georgia (1896) | First Lessons in Georgia History (1913) | The Georgia Story (1958) | Georgia: A Short History (1960) | Empire Builders of Georgia (1966) | Georgia History and Government (1973) | The Georgia History Book (1982) | Georgia in American Society (1987) | The Georgia Studies Book (1998) | The Georgia Journey (2018) |

| Slavery as the cause of the Civil War | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| States’ rights and the Civil War | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nullification and the Civil War | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| The Compromise of 1850 and the Civil War | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The Georgia Platform | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| The Dred Scott decision and the Civil War | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The debate over secession in Georgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The Union blockade of Georgia’s coast | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The Emancipation Proclamation | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chickamauga | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sherman’s March to Sea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Andersonville | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Discoveries

The oldest textbook reviewed was Charles Smith’s A School History of Georgia: Georgia as a Colony and a State from 1896. Lawton Evans had written the first Georgia history textbook 14 years earlier. His book was The Student’s History of Georgia: From the Earliest Discoveries and Settlements to the End of the Year 1883. It became the de facto Georgia history textbook and was used as source material for derivative works, including First Lessons in Georgia History, which is reviewed. First Lessons in Georgia History contained many Lost Cause myths, including the following:

Slaves lived good lives

Of course, there were many slaves in Georgia, as there were in all the Southern States. Over half the total population of Georgia were negro slaves. They worked in the cotton fields, slept in the quarters, were cared for by their masters on the plantations, and were as happy as their condition would permit. (p. 268)

Slavery was a constitutional right

The position taken by the Southern States on the slavery question was very simple. They maintained that the holding of slaves was a question that each State had a right to decide for itself, and that this right was one of the things reserved by the Constitution of the United States to the States themselves. (See Constitution of the United States, Amendments, Article X.) If the Northern States did not desire to have slaves they had a right to abolish slavery in their own limits as they had done. If, on the other hand, the Southern States desired slavery in their limits, they had a right to hold slaves, as they were doing, and the Northern States had no constitutional right to interfere. (p. 269)

Confederates were heroes

Toombs as an Orator.—He was a great and fearless orator, one of the most impassioned and daring that Georgia has ever produced. He loved the Union, as all the other Southern statesmen did, but he loved the Constitution more. … (p. 270)

States’ rights, not slavery, led to secession

From this time on many of the Southern people began to talk of secession. In the opinion of many it was the only thing the Southern States could do in justice to themselves. In the view of the hostile attitude of the Northern States against slavery, and the evident purpose to ignore the Constitution in order to abolish it, the Southern States felt justified in taking the position that they were no longer bound by the Constitution, and could leave the Union if they desired. (pp. 271-272)

Though Evans’ primary work was revised periodically, it was not until the 1950s that scholars began to abandon his scholarship and write new Georgia history texts for use in classrooms. Consequently, Georgia history texts from this era tell the history of the Civil War from a pro-Confederate point of view. The texts feature larger-than-life images of Confederate generals, congratulatory messages about Confederate victories, and depictions of plantation life in which Black people enjoyed their lives of enslavement.

Despite new voices interpreting Georgia’s history, Lost Cause ideas continued to be pervasive in textbooks well into the 1960s. Yet, inklings of a shift in thought began to emerge.

For instance, Ellis Merton Coulter, in his book Georgia: A Short History, described Confederate General Howell Cobb as having a “ponderous” voice, being charming, and loving the Union (p. 312), which is in line with the Lost Cause myth that Confederates were noble men. However, when it came to choosing between slavery or states’ rights as the cause of the Civil War, Merton took a “both-and” approach instead of falling squarely into the states’ rights position:

Slavery alone was not responsible for the war between the North and the South. Being more particularly the spectacular evidence of a civilization in the South different from what prevailed in the North, and being and institution opposed to the spirit of the times, it afforded an easy object of attack. As slavery was the keystone in the arch of Southern civilization, the South was maneuvered into a movement to set up a new nation, not so much to defend slavery as to protect the social and economic order which slavery made possible. In a final effort, the South was willing to give up slavery to win her independence and seek other means to preserve her own form of civilization. But even so, slavery was no mean part of that very civilization, and it would likely have been an impossibility for the South to save its ante-bellum self without the support of slavery. Without slavery, there would be a race problem; and the realization of this fact tied to this institution both slave-holders and non slave-holders alike, and explains in part why all fought with equal bravery in the war that came. (p. 303)

While Coulter’s writing reveals that he is pro-Confederate, subsequent textbook authors, perhaps recognizing that history is far more nuanced than black or white, followed Merton by presenting primary and secondary causes for the Civil War.

It was not until the 1970s that Georgia history textbooks began to promote a more balanced, progressive view of slavery and the Civil War. For instance, Albert Saye, in the 1973 edition of his textbook Georgia History and Government, wrote that “slavery was the rock upon which the Union crashed” (p. 120) and acknowledged that “most people outside the South came to view slavery as the basic issue in the war.” (p. 131) In addition, Saye begins a tradition, missing from all prior Georgia history texts, of giving space to the United States and Confederates, comparing and contrasting leading figures from both sides and presenting primary sources, such as an excerpt from Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

Older generations of Georgians learned an inaccurate conservative Georgia history that consisted of Lost Cause mythology. The textbooks from the 1980s and 1990s indicate that Georgians of that period and later learned a similar set of facts delivered in a more accurate, neutral manner that features more primary sources, perspectives, and less Lost Cause ideology.

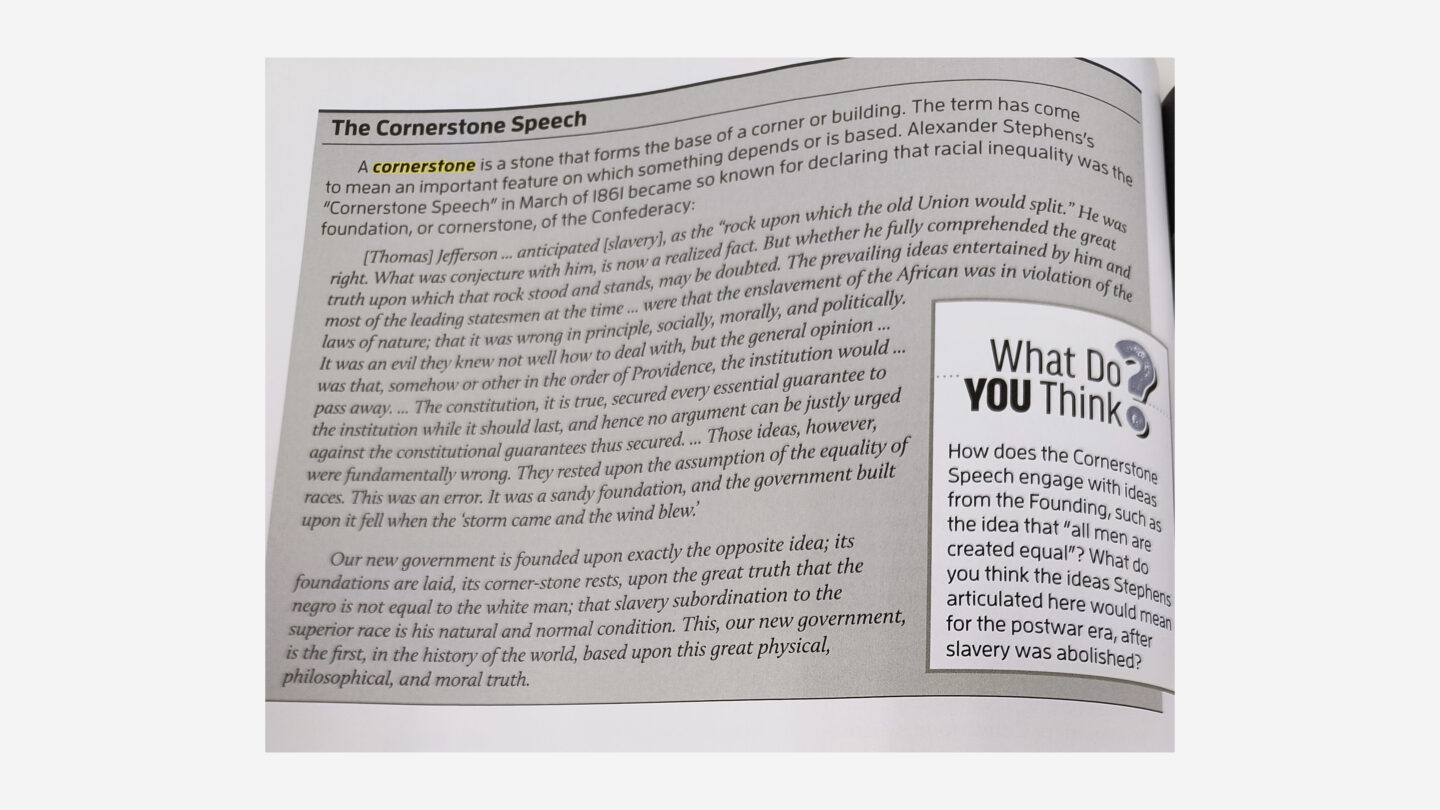

Modern textbooks such as Gibbs-Smith’s 2018 book, The Georgia Journey, seem to continue with the precedent set by texts in the 1980s and 1990s. Gibbs-Smith’s book includes primary sources, such as a narrative that gives a neutral summary of the war. Because ideas and historical figures such as Howell Cobb, Robert E. Lee, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. Grant are introduced within the confines of appropriate historical context, there isn’t any discernible Lost Cause ideology.

The past is malleable and flexible, changing as our recollection interprets and re-explains what has happened.

Conclusion

The evolution of Georgia history textbooks illustrates the effect of politics, social norms, and cultural values on historical narratives. From pro-Confederate views and Lost Cause mythology of early textbooks to more balanced and nuanced approaches of modern textbooks, the changes in Georgia history education reflect not only the evolution of historical scholarship but also the shifting perspectives of Georgians on their past. While older generations of Georgians were exposed to a distorted version of history that perpetuated the myth of a glorious Confederate past, modern Georgians are presented with a more accurate and critical view of the state’s history, one that takes into account the complex and multifaceted nature of historical events. By understanding the evolution of Georgia history textbooks and the role of shared memory, we can appreciate the role of education in shaping our understanding of the past and recognize the need to constantly reassess and revise our historical narratives to reflect new knowledge and changing perspectives.

Resources

Exceed the Standard: Civil War

Georgia Encyclopedia: Georgia History Textbooks

Georgia Department of Education: Social Studies Standards of Excellence

Digital Library of Georgia Educator Resources (SS8H5)