The painting was actually completed in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

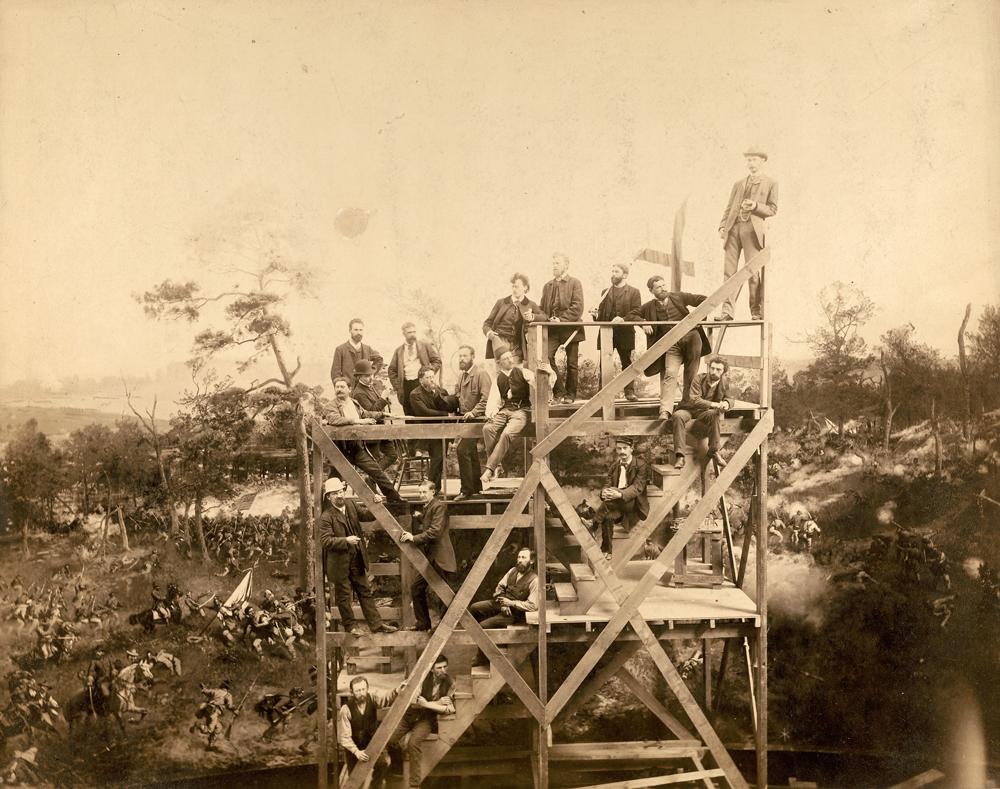

After The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting was relocated to Atlanta History Center for extensive restoration in 2017, I got to lead behind-the-scenes tours of this fascinating work of art. While those tours have been suspended during the installation of the exhibition, here are some of my favorite tidbits.

Given its focus on the Atlanta battle, it’s easy to assume that The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama was painted in Atlanta. In fact, it was completed in 1886 by the American Panorama Company — in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

There are some clues to the painting’s origins and intended audience. The subject of the artwork is one of the four U.S. battlefield victories that led to the defeat of Confederate troops and evacuation of Atlanta in 1864—a moment that Northern, rather than Southern, veterans no doubt wanted to celebrate. This outcome convinced Northern voters that the war could be won and that Lincoln was the right man to get the job done, which secured his reelection.

Another indication of the painting’s Northern origin is its inclusion of Old Abe the War Eagle, the spirited mascot of a Wisconsin regiment, soaring high above the battlefield. In truth, he was never actually permitted to fly over the battlefield freely (despite his patriotism, there was some concern he would not return). In fact, he was not even at the Battle of Atlanta. So why is he in the painting? It’s likely that, because Old Abe became a symbol for all Wisconsin soldiers, Civil War veterans in Milwaukee wanted the artists to include a nod to Wisconsin roots.

The painting is bigger than it appeared at Grant Park.

If you remember the painting seeming smaller than it is now, you’re right!

Cyclorama paintings were created to be a standard size of 375 feet in circumference and 50 feet in height, enabling the paintings to travel between standard-sized buildings in different cities.

Each time The Battle of Atlanta was moved (six times before 1921), the top edge was cut off the circular overhead beam holding up the painting. Then the painting was rolled up for transportation. These moves, along with bad weather and poor display conditions, resulted in 7 feet of sky and a 54-inch wide vertical section being removed. Additionally, the new fireproof building constructed in Grant Park in 1921 to accommodate the painting was too small and resulted in another 22-inch wide vertical section being removed to squeeze the painting into its new home. Since its move to Atlanta History Center in 2017, conservators have added back all of the missing canvas (just over 2,900 square feet) to restore the painting to its full size for the first time since 1886!

The cyclorama was touched up, restored, and tweaked over time.

Even though the painting was completed in 1886, there have been many changes to it over time.

The Battle of Atlanta depicts a critical United States victory, much to the delight of its intended Northern audience. Eventually though these audiences got tired of cycloramas; there were at least 40 paintings touring that region. So, in 1891, The Battle of Atlanta was snatched up by Southern businessman Paul Atkinson to test its appeal with Southern audiences. With this shift came a problem—how could Atkinson make this painting appeal to a very different perspective? Simple. He made several small, but meaningful, edits—including to the soldiers pictured above. Certain that the sight of Confederate prisoners would offend his audience, Atkinson had these figures repainted to make them look like cowardly United States soldiers fleeing the battle.

During the 1934–1936 restoration, local artist Wilbur G. Kurtz repainted these “fleeing Yankees” and made them Confederate prisoners again.

Bonus: The artists painted Easter eggs into the painting — including themselves.

Say hello to Theodore Davis—technical advisor to the cyclorama artists. He served as a combat artist during the real Battle of Atlanta and included himself in the painting as a soldier on a white horse. While the painting was exhibited in Indianapolis in 1888, the Davis figure was repainted to depict U.S. Colonel and Presidential candidate Benjamin Harrison. Davis’s likeness was restored in 2018 by Atlanta History Center art conservators.

The diorama figures were not part of the original cyclorama painting.

The diorama—the faux terrain surrounding the base of the painting—was always an essential part of the cyclorama’s immersive illusion. The diorama figures, however, were not. When the painting was restored between 1934 and 1936, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), sculptors added 128 plaster soldier figures. The diorama surface was real Georgia red clay studded with logs and tree stumps. While this certainly provided an authentic look, it also attracted authentic pests. Poisons were applied to the back of the painting to deter these critters, but have no fear—these poisons were carefully cleaned and removed during the next restoration in the 1980s.

Today, the diorama surface is fiberglass with a layer of Georgia red clay mixed with Aqua Resin (so critter-proof), but includes the original 1930s figures. These figures have been meticulously restored so they can continue to be an integral part of the cyclorama experience.

There’s only one non-white figure in the entire painting.

There are at least 3,000 figures in the foreground of the painting, and perhaps twice that number in the background. But the above figure is the only African American figure in the painting. Is he an enslaved man running to U.S. lines to escape bondage? Is he a free man working for the U.S. Army? These are possibilities as both scenarios were common, but unfortunately the artists left no clear information.

One thing we do know about this figure is that he is not a member of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), the official all-black regiments of the United States Army during the Civil War. Not only is he not wearing a uniform, but U.S. Major General William T. Sherman, who led U.S. Army troops in this battle, did not allow USCT soldiers to fight in his ranks. Nonetheless, African Americans did perform important jobs as teamsters, cooks, and general laborers for Sherman’s army. As an example, at least 400 African American cooks served as stretcher bearers during the Battle of Atlanta.

The ratio of one African American to 3,000 whites shown in the painting does not accurately reflect the extent of African American involvement in the U.S. war effort. Remember that The Battle of Atlanta is a work of historical fiction created as entertainment, and so it only hints at the broader historical event that was the Civil War. That’s why we’ve included these lesser-known stories and unheard voices in the new exhibition surrounding the painting at Atlanta History Center—these are an essential component in connecting the painting to the big picture of how we remember our shared history.

More information is available at atlantahistorycenter.com/cyclorama.

Jessica Gordy is the Manager of Guest Experience at Atlanta History Center. During the restoration of The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting, she developed and led Behind the Scenes Cyclorama Tours.