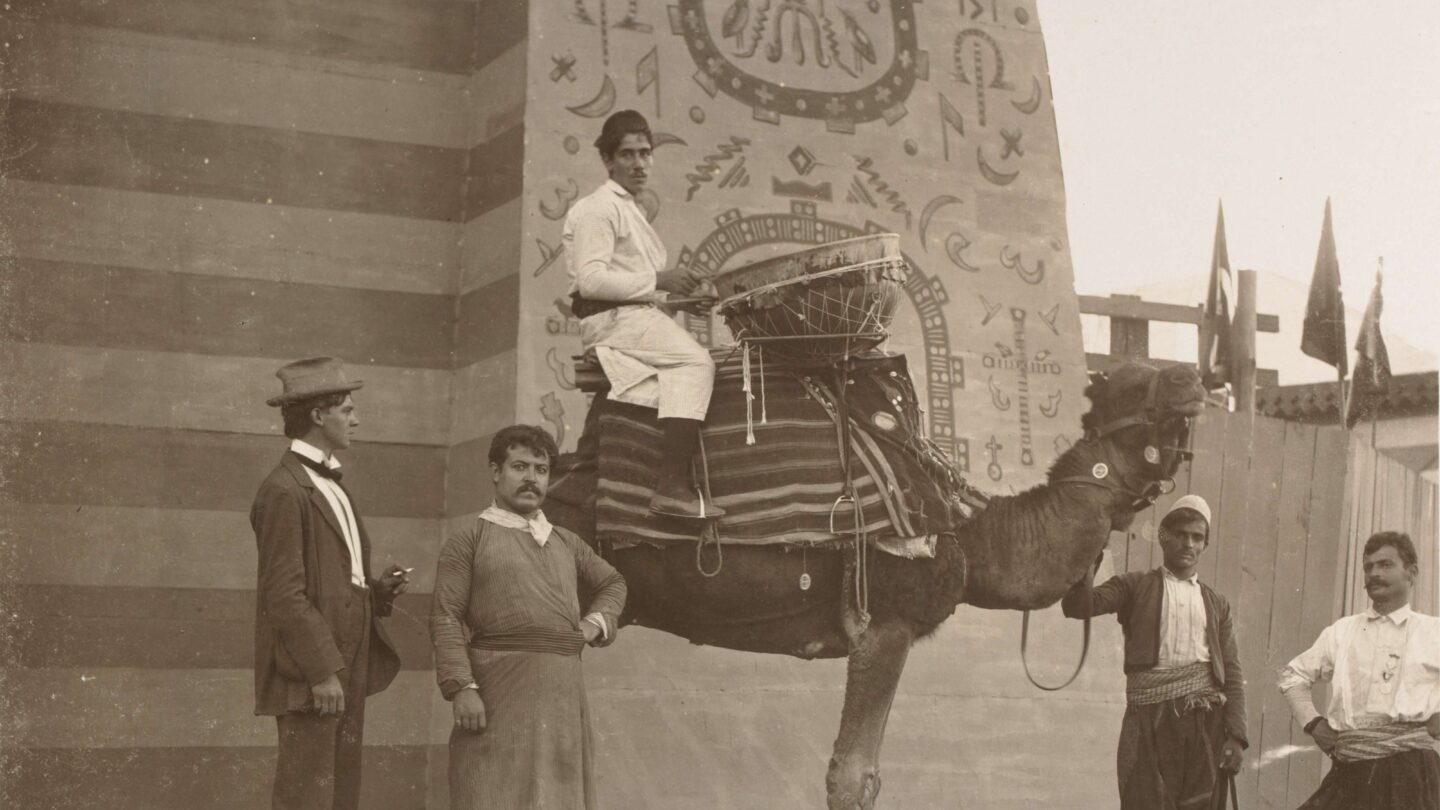

Bird’s eye view drawing of the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition grounds in Piedmont Park in Atlanta. W. L. Werner, Stoddart Company, Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

On the morning of September 18, 1895, the gates of Piedmont Park opened onto a temporary city of towers and domes. Bands struck up, flags snapped along wide promenades, and crowds funneled toward an auditorium where Booker T. Washington would soon speak. Beyond the Chimes Tower, state buildings — exhibition pavilions built by individual U.S. states to display their industries, agriculture, and cultural achievements — framed terraces that rose in levels of 22, 30, 40, and 50 feet, linked by granite-railed stairways. Across the way, Lake Clara Meer — roughly 12 acres and 25 feet at its deepest — glittered with an electric fountain: a central geyser, rings and “wheat-sheaves,” oscillators, and a new “mist-bank” of colored light that “enveloped the fountain in a dense mist of spray.”

The bridge over Lake Clara Meer in Piedmont Park during the Cotton States and International Exposition in 1895. Fred L. Howe, Fred L. Howe 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Situated in the park as the centerpiece were 11 principal exposition halls. They were adorned with Georgia-pine shingles “creosote”-stained a dark silvery gray, with moss-green roofs and dull-white trim — an intentionally unified palette against the park’s green slopes — and about 6,000 exhibits. The Fine Arts Building was designed by Atlanta’s Walter T. Downing, the Woman’s Building by Elise Mercur of Pittsburgh, and the U.S. Government Building by Charles S. Kemper.

Inside the buildings, modernity was not just claimed; it was demonstrated. In the Electricity Building, rivals General Electric and Westinghouse set up facing displays, while American Bell Telephone commanded the largest footprint. Glass cases held kinetoscopes — an early version of moving pictures — and switchboards and motors hummed. For many, this was their first close encounter with the power and promise of electricity.

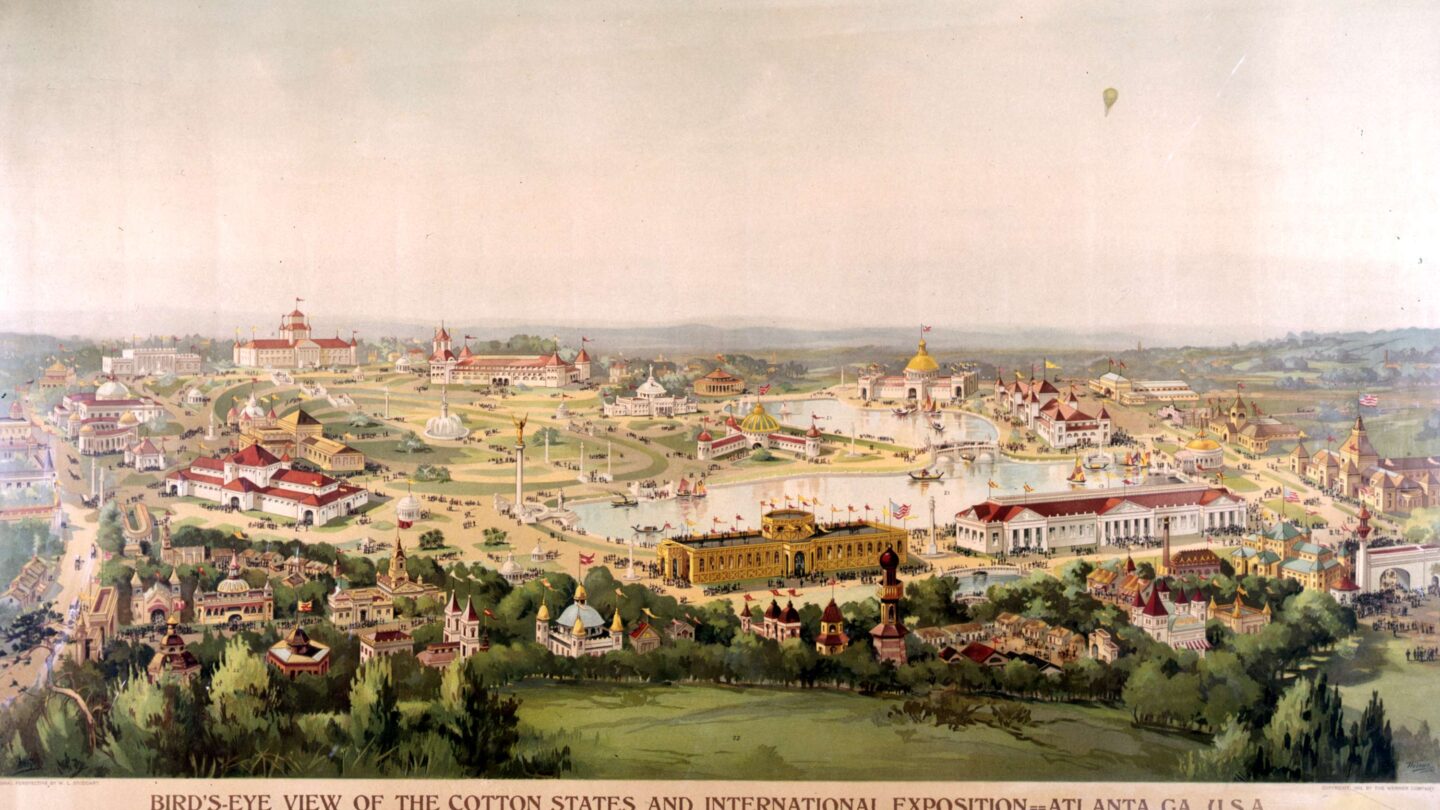

Unidentified men, women, and children in an oxcart on an excursion visiting the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. B. W. Kilburn, Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Across the way, Machinery Hall concealed its power in a subfloor maze of shafting. On the floor above, 2,250-horsepower engines drove looms, woodworking lines, and the latest printing technology: a Miehle press, Campbell’s Pony press, and a Thorne typesetting machine that seemed to think with its clattering arms. The hall was a noisy argument for Atlanta’s claim to industrial leadership.

In the Minerals and Forestry Building, even the lighting was part of the lesson. Welsbach incandescent gas lamps used mantles described then as made from monazite sand “found only in North Carolina,” casting a soft blue glow. For a public still accustomed to kerosene, the effect was nothing short of magical.

Women’s leadership had a dedicated stage topped by a statue of Immortality. Planned, managed, and run entirely by women, the Woman’s Building served as a manifesto that women belonged in the civic and professional life of the city. The following were inside the building: a cooking school, an emergency hospital, a kindergarten and day nursery, a library and press room, and a packed schedule of congresses and concerts. Exhibits filled some 35,150 square feet across three levels.

The Negro Building — described at the time as the first hall at a major exposition devoted entirely to Black exhibits — stood near the Jackson Street entrance. Black contractors and laborers built the hall, and its pediments paired a log cabin scene with a portrait medallion of Frederick Douglass, creating a pointed before-and-after contrast. A central tower hosted Jubilee singers; inside, institutions from Atlanta University, Spelman, Morehouse (then Atlanta Baptist Seminary), Howard, Tuskegee, and others filled the aisles. The building opened on October 21, 1895, a month into the fair. December 26, 1895, was designated “Negro Day,” drawing additional attention and visitors, including quilter Harriet Powers.

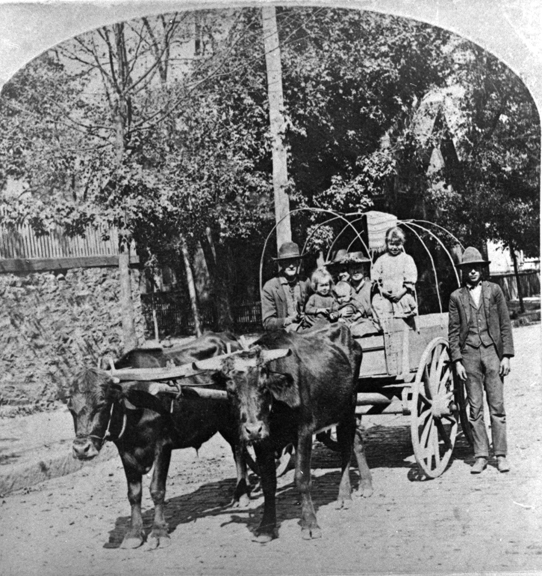

The midway featured attractions that can only be described as pure Gilded Age: the Phoenix Wheel, Atlanta’s answer to the Chicago Ferris wheel, a moving-picture theater, water rides, a reunion of Union and Confederate soldiers, even a University of Georgia–Auburn football game, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and the Liberty Bell. It was entertainment meant to draw crowds and reinforce a deeper narrative of progress.

When the lights went down, the grounds themselves became an argument for Atlanta’s modernity. The model electric-light plant “banishing night,” three miles of water mains, and “four and a half miles” of sewers laid to ensure “perfect sanitary conditions” spoke to Atlanta’s ambition to be seen as a modern city.

This was the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, a spectacle that welcomed about 800,000 visitors from 37 states and foreign countries over the fair’s 100 days. It was the culmination of a 15-year campaign of civic boosterism powered by earlier fairs.

Atlanta’s first fair, the International Cotton Exposition of 1881, occupied Oglethorpe Park and signaled the city’s bid to be an industrial hub. A more regional showing followed in 1887: the Piedmont Exposition, which drew President Grover Cleveland and tens of thousands of visitors. These events — championed by Atlanta Constitution editor Henry Grady — taught Atlanta’s boosters that spectacle could be strategy.

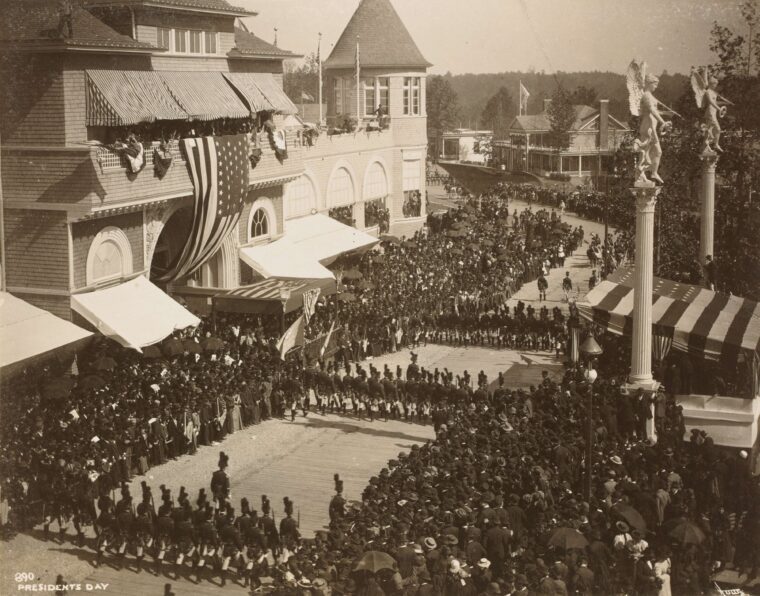

A crowd gathers for President’s Day to celebrate the arrival of President Grover Cleveland in Piedmont Park during the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition. Fred L. Howe, Fred L. Howe 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

By late 1893, former mayor William Hemphill had pitched something grander. The exposition’s Official Guide begins the origin story bluntly: “Col. Wm. A. Hemphill is credited with being the originator of this stupendous enterprise.” He first floated the idea on Christmas Day that year.

The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition was funded by a mix of public subsidies and private investment. Atlanta and Fulton County each put up $75,000. The railroads added $50,000 in cash and offered discounted shipping rates to help exhibitors and visitors. The state of Georgia contributed $20,000, while Congress appropriated $200,000 to cover federal exhibits. A private exposition company was also formed, raising $200,000 by selling stock to local investors.

The money funded not only a fair but a larger mission: trade and transformation. Organizers declared the exposition’s objective was to cultivate closer trade relations with South, Central, and Latin America. The Official Guide reprinted Atlanta Constitution editor Clark Howell’s figures showing the United States bought $207,384,389 worth of goods from Latin America but sold back only $90,804,640 — “an unnatural condition,” he warned. Atlanta, Howell argued, could correct the imbalance by promoting Southern mills and encouraging trade across the hemisphere. Beyond trade, the calendar of “special days” during the fair — Blue and Gray Day, the National Council of Women, and December’s Congress on Africa — underscored how the event pitched Atlanta as both an industrial hub and a stage for reconciliation and reform.

The District of Columbia exhibit in the Negro Building in Piedmont Park during the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. Fred L. Howe, Fred L. Howe 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The success of the exposition cemented Atlanta’s claim to regional leadership after the devastation of the Civil War. Yet it also revealed the era’s contradictions. Washington’s address was celebrated by white boosters but contested by Black leaders; the Negro Building offered an official platform while reinforcing segregation; and a festival of progress unfolded as Jim Crow tightened across the South. These political tensions lingered long after the fair closed, shaping the city that grew around the park. In 1904, the city purchased the exposition grounds, and it became a public park.

Piedmont Park’s Lake Clara Meer with the Midtown skyline in the background. Frank Schulenburg, Wikimedia Commons

Today’s Piedmont Park — and later the Atlanta Botanical Garden — is the fair’s most visible legacy. To walk the park today is to trace those choices — the spectacle, the sales pitch, and the silences — etched into lawns, terraces, the man-made lake, and granite steps first laid for the fair, physical reminders of a season when Atlanta staged its ambition. In its quiet endurance, Piedmont Park silently recognizes the central idea of the exposition: Atlanta as the confident capital of a rising “New South.”