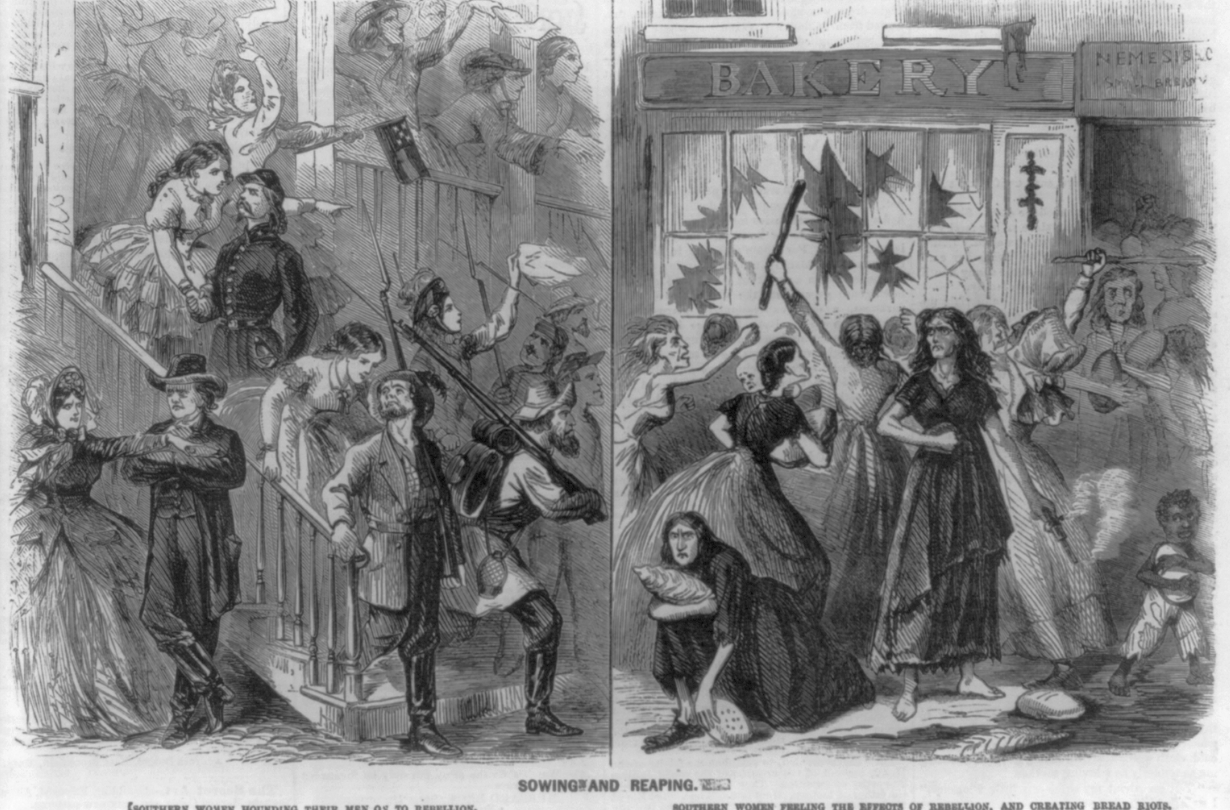

A comic depicting the Women’s Bread Riot of Mobile, AL in September of 1863, from the weekly journal Pictorial War Record: Battles of the Late Civil War in 1883, Encyclopedia of Alabama.

In the spring of 1863, amidst soaring inflation and material deprivation, a cascade of armed riots and robberies took place across much of the Confederate States. Occurring in both rural and urban areas, these uprisings were led by white women, many of whom belonged to the yeoman class of small rural farmers. A large proportion of them were also Confederate soldiers’ wives. Their loot was primarily food, cloth, wool, salt, shoes, and other daily necessities.

The largest and most destructive riot took place on April 2, 1863, in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Possibly as many as five thousand women, and some men, united to appropriate goods. But on March 18, two weeks prior to the Richmond Bread Riot, 10 to 20 white women in downtown Atlanta lit the fuse that started it all.

Led by a “tall, determined woman,” this group stopped in front of a storefront and inquired about the price of bacon. The shopkeeper told them it was a dollar and ten cents per pound. The tall woman pointed out the “impossibility of females in their condition” paying such a large sum for meat on Confederate army wages, but the shopkeeper refused to lower the price. The lead woman, in response, pulled a long navy revolver from her breast and pointed it at the shopkeeper. While holding the man at bay, she then instructed the women to take what they needed, which they did.

Though Richmond had the biggest riot, Atlanta was home to the first one.

After leaving the store, they explained to onlookers why they had taken this violent course of action. According to newspapers, their “families had been deprived of anything to eat…save a small portion of cornbread,” and their “suffering condition” is what drove them to act. This robbery would instigate a chain reaction of similar uprisings across the Confederacy. Women armed with bowie knives, repeaters, shotguns, pistols, axes, hatchets, and other armaments began rising rapidly and spreading from Atlanta into other parts of Georgia, such as Macon, Augusta, Milledgeville, Butts County, Pickens County, and more. They spread beyond Georgia, most notably into North Carolina, Virginia, and eventually Alabama.

Civil War Women’s Riot Marker in Columbus, GA, courtesy The Chattahoochee Voice.

Many of these robberies would take place in broad daylight, and targets included government property as well as military convoys. Signs carried by the crowds read “Bread or Blood” and “Bread or Peace.” Men and women were arrested and sentenced to five years in jail. The audaciousness displayed in these raids sent shockwaves through the Confederate government, causing some declarations of support for the Union army from mountainous areas of the South.

What led women to this point?

Because vast percentages of the Confederate population were enslaved, military officials had to dig deep for recruits. By the end of 1862, all able-bodied Southern white men between 18 and 35 were required to serve. Many poor male yeoman farmers were pulled away from their fields and the crops needed to feed themselves and their families. Aggressive Confederate military provisioning of food further reduced harvests. State governments requested wealthy planters grow more food crops instead of cash crops like cotton, but the requests were unheeded.

To compound matters, the lower South received many refugees from the upper South, rapidly filling urban spaces. Women from lower South rural counties also entered nearby lower South cities, looking for work in war industries to compensate for low crop yields. With insufficient aid, these desperate communities would be the primary instigators of the riots.

Hunger quickly spread, creating desperation.

Animosity toward wealthy planters and speculative merchants was also a major instigating factor. The Twenty Negro Law, which had passed in 1862, allowed men of conscription age to be exempt from the draft if they enslaved more than 20 people. This exemption was deeply unpopular with poor Southern whites, who owned very few or no enslaved people. Additionally, the state legislature’s attempts to compensate slaveholders for the deaths of enslaved people who died while constructing Confederate fortifications also caused some anger among the women. One North Carolinian participant of the riots wrote in a letter to the governor of North Carolina the following:

“We has sons, brothers, and husbands now fighting for the big man’s negro, and we are determined to have bread out of their barns or we will slaughter as we go.”

Price speculation was also common in this period of high inflation. Merchants, whether guilty or not, were often accused of hoarding goods and artificially raising the cost of necessities. Another North Carolinian, Mary Moore, a participant in the robberies in Salisbury, wrote the following:

“Our husbands are separated from us by the cruel war not only to defend their humbly homes but the homes & property of the rich man.”

Moore also argued that her compatriots only took what was owed to the people because of the sacrifices made by their husbands.

Notably, many of the merchants targeted by the raiders were foreign-born. It’s possible they were perceived as more untrustworthy than their non-foreign-born counterparts.

A newspaper comic contrasting Southern women from the start of the war in 1861 to the Spring of 1863. “Sowing and Reaping”, originally published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on May 23, 1863, courtesy Library of Congress.

What Happened in Response?

Responses to the raid varied. Many Southern newspapers couldn’t believe women could organize such widespread and rapidly growing political actions. Mischief makers and “Northern agitators” were speculated as being the real culprits. Other papers said the women had “unsexed themselves,” calling them “viragos” and “amazons.” One publication called them “prostitutes, professional thieves, & jailbirds…hailing from different parts of the country.”

The government’s response was largely sympathetic. Many towns and cities already had private institutions dedicated to helping the poor, orphaned, and widowed, but additional groups popped up across the South in response to the riots. Georgia had already begun creating a public welfare system for poor whites in the state, though it was often inadequate. However, after the riots, Georgia and six other Southern states would build welfare systems larger than any preexisting ones in United States history. Georgia, for example, spent more on domestic economic support in one year of the war than Massachusetts had during the whole conflict.

Government stores were also set up as alternatives to the private market, selling necessary goods at lower prices than their inflated value. Ironically, two days prior to the initial Atlanta robbery, Georgia’s governor, Joseph E. Brown, had written to CSA vice president Alexander Stephens, saying that “our ultimate success depends on the bread supply.” Families of Confederate soldiers would eventually receive corn at no charge, and eventually corn was provided free to anyone who needed it (except Unionists, the enslaved, and the free Black population.)

Columbia University historian Stephanie McCurry argues that the importance of these riots lies in the political mobilization of these lower-class women. She writes the following:

“In the CSA, the government reached far past the ranks of those white men called upon to serve to their dependents—the women, children, & enslaved who made up the massive enfranchised southern population.”

These women’s riots contradicted the dominant image of southern white women as steadfast, loyal, and devoted supporters of the Confederacy.

Without access to the ballot box or the ability to influence peddling, poor white women took direct and radical action to demand their needs. They used more traditional political means, such as communicating with the press and writing letters to their representatives to make clear their intentions and complaints. They made it clear that their commitment to their cause was deadly serious.

A Georgia state legislator wrote that a woman in the Milledgeville riot insisted that if the women’s needs were not met, then their husbands “would not lay down their arms and come home but would come gun in hand, and there would be more bloodshed than was at Bunker Hill.”

This reference to the coordinated politics of poor Confederate soldiers and their families is corroborated by research showing higher desertion rates for soldiers in counties where bread riots had taken place. Throughout the war, multiple southern regions would also see violent resistance from Confederate deserters and Unionists, such as Jones County, Mississippi, and West Virginia.

These women’s riots contradicted the dominant image of southern white women as steadfast, loyal, and devoted supporters of the Confederacy, supportively sending their husbands, fathers, and sons into battle and and committing to anything needed to combat the invading federal forces. Instead, it shows a prevailing class-based conflict before the war, bubbling up to the surface with violent consequences as well as a radical repudiation of Confederate domestic economic policy.

It must be noted, though, that while these women made demands for greater economic and nutritional support for their own families, any substantial support for abolition, political solidarity, or relief for the enslaved was a distinct minority. This is despite the fact that enslaved mothers, wives, and sisters endured even harsher conditions than those criticized by the yeoman women of the Confederate Bread Riots.